Robohub.org

Nursing Grandma with a robot

All this talk about being replaced by robots is getting old.

All this talk about being replaced by robots is getting old.

My grandmother got run over by a cable car in San Francisco when she was about six and she wore a wooden leg after that. Of course she hated it. In the glamor days of the 1930s, when the miniskirt look was in (and the steampunk look was not), her wooden prosthetic put her into a social category of Blackbeard more than Greta Garbo.

When I was a kid we’d have weird family outings to go get her a new leg. She’d complain about it but it was still enough of a party that I always got an ice cream from the deal. We did our best to take care of her but she always hated that wooden leg.

Later we put Grandma in a nursing home. I felt bad because I couldn’t see her as much, but I was in college, mom was working, and we had other responsibilities. We did, however, get her a pretty nifty electric wheelchair. I later glued on some fancy sequins, which added a glamor factor at the bridge tournaments in the cafeteria. It was classier than her wooden leg, and it edged her a little closer to her Greta Garbo image.

But glittery electric wheelchairs aside, we had neither the time, the family members, nor the money to take care of her as she deserved. We did what we could with the sequined wheelchair and the weekend visits.

A robot would have come in handy. Here’s why.

Over a third of American adults are family caregivers and most of us already have a job.

By 2050, 16 percent of the global population will be over the age of 65. That’s 1.5 billion people, according to The Population Reference Bureau.

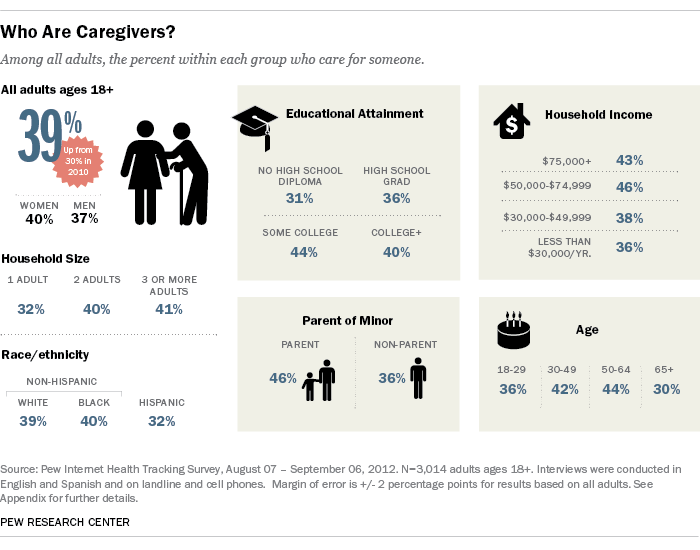

In June, 2013 the Pew Research Center published the report Family Caregivers are Wired for Health. According to the Pew survey 39% of Americans said that they had “provided unpaid care to an adult relative or friend 18 years or older to help them take care of themselves” in the previous year. 70% of the caregivers had other jobs, which means that they’ve got a lot more to do than take care of Grandma. Also, according to a previous Pew study, 47% of American adults say that they expect to be a caregiver for an elderly relative in the future.

Then, about a year later, Pew released another survey – U.S. Views of Technology and the Future – which showed that 65% of those surveyed thought it would be a change for the worse if robots become the primary caregivers for the elderly. And in May of this year The Guardian ran a survey and found that about half of those surveyed thought technology was evolving too quickly and undermining traditional ways of life.

Hence the question is on everyone’s lips …

Should we have robot caregivers?

In academic circles the debate rages. Dudley and Emery wrote “The Value of Caregiver Time” (2014. From MIT’s Lee, Stiehl, Toscano, and Breazeal we have “The Semi-Autonomous Robot Avatar As a Medium for Family Communication and Education” (2009). And from CMU’s Borenstein and Pearson we have “Robot caregivers: harbingers of expanded freedom for all?” (2010). The February 2013 edition of, “GeroPsych: Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychology” published a special issue with a series of interesting articles. Fox, Kleinman, and hundreds of others have researched this problem and come to the same core question: Should we?

Sherry Turkle, of MIT, says Nay. She’s launched several invectives against the army of healthcare providers she sees coming over the horizon. A clinical psychologist, Turkle has written that “faux relationships detract from human connections…” and “make us less likely to look for other solutions for their care.”

Mainstream media have started pouring gas on the debate as well. Heather Kelly of CNN has asked if robots are “… the future of elder care?”; Health and Medicine explains why patients tell more secrets to virtual humans, and on July 19th of this year Louise Aronson wrote about the future of robot caregivers, arguing that we need them. A few days later, Turkle replied to Aronson’s article, stating that we are in the process of “outsourcing” our ability to care for one another. She and many others claim that our modern media makes us feel lonely.

Robots: The latest victims of the “Technology Makes Us Lonely” meme

In Turkle’s paper “In Good Company” she argues that healthcare robots are cause for grave concern, especially if we expect to have family members replaced by them. She argues that outsourcing to hospital robots should not be done lest we ruin our families, automate our interactions, and become lonelier as a result.

This “Technology Makes Us Lonely” meme has been going around like a bad case of the sniffles. The Atlantic ran a cover story on it back in May 2012 and Turkle wrote a similar op-ed piece in the NY Times to publicize her book “Alone Together”. William Deresiewicz, a literary critic, wrote of “the loneliness of our electronic caves … The more people we know, the lonelier we get … We have given our hearts to machines, and now we are turning into machines.” Meanwhile books like “The Lonely American” and articles about how we’ll not end up just lonely, but broke as a result of robots, give the impression that the Cylon uprising will commence this weekend in a nursing home near you.

Reading this stuff is enough to make anyone lonely. But none of this may come to pass at all. Family members aren’t at risk of being replaced by robots any more than conversations were at risk of being replaced by telephones.

We’ve heard these Manichaean arguments before. We’ve heard of the negative effects of video games, the negative effects of movies, or how “Each hour spent viewing television is associated with less social trust and less group membership,” wrote Robert D. Putnam, a government professor at Harvard who researched the ills of television in the 1950s.

Telephones were supposed to make us lonely, too:

Does the telephone make men more active or more lazy? Does [it] break up home life and the old practice of visiting friends?

— Survey conducted by the Knights of Columbus Adult Education Committee, San Francisco Bay Area, 1926

Robots are facing the same firing squads as other media have , and they will become an integrated part of – not a flat replacement for – what we have today. More moderate experts, like Professor Maja Mataric, offer us a nuanced view than Turkle. Mataric points out that care robots aren’t a substitute for human interaction. In an article with the San Jose Mercury News she says, “there just simply aren’t enough people to take care of our very large and growing elderly population … We need to think about the humane and ethical use of technology, because these things are coming.”

Robot caregivers are coming

Let’s set aside nostalgia; we now live in the future. Whether we like it or not, robots are now healthcare providers. Both the horrible and the lovely exist in front of us and these systems will be caring for you and me when our kids don’t have the time, desire, or money to do so themselves.

And this might not be such a bad thing. On the provider side we can already see examples of assistance with surveys, assessments, triage, and assignment. On the patient side we can see great examples of advice, entertainment, mental stimulation, games, and simple companionship that the 80 million people entering the healthcare system this year simply won’t be able to get otherwise. These systems offer increased value that is scalable and cost effective.

Just the companionship use-case is a great one. After all, isn’t it worth offering your grandmother both the crossword puzzle she does today as well as a robot that will offer clues as she does it? Isn’t it better for them to have a helping hand beyond just the crossword puzzle?

And isn’t it the case that having options is what liberates us?

Geppetto Avatars Sophie

I’m biased for many reasons. One of them is because Geppetto Avatars, my own company, builds natural language avatars for healthcare and other applications. We’re proud to partner with IBM Watson, EBSolutions, Tailored Care and other companies so that we now have healthcare knowledge that is more up-to-date, evidence-based, and broader than any single, trained doctor can provide alone. Our avatar Sophie can play bridge as well as the next senior citizen (and chess and other games as well as perform surveys and offer healthcare suggestions), and while she can’t stop a speeding train, she can offer help across a range of subjects.

There are other companies like us that also provide software robots. There’s NextIT‘s project that helps soldiers, students and elderly. There’s both Catalia Health and Intuitive Automata, founded by Dr. Cory Kidd – an expert in building social, affective robots to help people lose weight and generally change behavior. There’s the Cantoche, which allows customers to make their own healthcare avatars, similar to Code Baby, Expect Labs, Arquiware. Other companies in this space are Sense.ly, which offers a virtual nurse, or Engineered Care‘s virtual nurse that’s there to provide daily support; MedWhat is a simple Q&A interface that’s partnering with avatar builders. These companies all provide the hearts and minds of robots, displaying, like the humans they care for, a wide range of emotional intelligence.

Meanwhile, in the American eldercare space, some 50 million people need help. And on average, a patient visits with their doctor for average of about ten minutes, and is interrupted by their doctor in the first 17 seconds of the conversation. There just aren’t enough doctors to go around.

There just aren’t enough doctors to go around

Luckily there’s another species of healthcare robot that allows a doctor and a robot work in collaboration as a hybrid: the telepresence robot.

Systems such as MantaroBot, VGo, Suitable Tech’s “Beam,” or AnyBot’s “QB” are four excellent examples. These robots are a physical prosthetic of a remote user. These telepresence robots help us get places we couldn’t be. If Turkle &co were to wave a flag and say that these robots prevented us from visiting our families, she would be missing the very essence of what these technologies do, which is to share time when we can’t share space. Telephones didn’t stop us from having conversations; they allowed us to break the barriers of space to facilitate more of them.

Systems such as MantaroBot, VGo, Suitable Tech’s “Beam,” or AnyBot’s “QB” are four excellent examples. These robots are a physical prosthetic of a remote user. These telepresence robots help us get places we couldn’t be. If Turkle &co were to wave a flag and say that these robots prevented us from visiting our families, she would be missing the very essence of what these technologies do, which is to share time when we can’t share space. Telephones didn’t stop us from having conversations; they allowed us to break the barriers of space to facilitate more of them.

Whether they’re software or hardware based, these robots don’t render family members obsolete; like telephones, they extend our reach. They’re prosthetics that help family members do a better job. And they can play bridge with Grandma now, too.

Healthcare robots are like any other healthcare tools – think of them like a splint, an x-ray machine, a wheelchair, or medication.

We need to be aware of how to use robots. We need to encourage users to be aware of the potential side-effects, detriments, benefits, pleasures, sicknesses, doses, withdrawals, and addictions. If we can approach technology (be it radio, television, telephone, Internet or video games) like a prescription drug then these conversations get a bit less dopey. Edward Snowden pointed out one of the side effects of social media (“Surveillance!”), the NSA has pointed out another (“Terrorism!”).

We need to weigh costs, risks, side effects and benefits. Yes, some people will become heavy addicts just as others will practice righteous abstinence. But we need a moderate dialogue to avoid extremes.

To claim that we all should – or should not – do something to address the dialogue around robots in such extreme terms is to incite a “War on Robots”. And this (like the “War on Drugs”) could leave people currently in hospitals in prisons instead (by footnote there are over eight million elderly Americans currently incarcerated. In August of 2014, the Urban Institute released a report that noted the increasing financial healthcare burden, suggesting that these inmates could use robots as well as my own grandmother).

Like drugs, robots will be ‘good’ or ‘bad’ depending on how people design and use them. Our imagination is what will guide the technology.

My Grandmother wasn’t in prison, but it was close. Some nursing homes and eldercare centers have horrible records of abuse, neglect, and cutting financial corners that have even lead to death. But connected systems like Paro or GiraffPlus could be used to help make sure that Grandma’s health is where it should be, and that she is active, alert, and engaged.

Robots offer luxuries most elderly people don’t have: surveillance, privacy, social status, companionship.- Surveillance: Robots can not only help with some of the above direct benefits to payers and providers, but they can assure family members that the elder person is receiving the care that is their due, and that the nursing home is taking appropriate steps to look out for their health. This surveillance, as well as input of user data via camera and microphone, is able to measure emotion, mood, sentiment and affect.

- Privacy: Just like a diary or a confessional booth can provide conversational privacy, people seem to prefer talking with avatars, especially about their health. Multiple studies (1, 2, 3) have shown that people are generally more comfortable talking with an avatar, especially in a healthcare setting. Robots can also help with very simple private tasks, such as helping someone go to the bathroom, change a bedpan, or other privacy-related tasks that you and I would not want a person to help us with.

- Social status: Just as people consider the iPhone or a fancy car as a sign of wealth, a robot that answers the door can be a sign of social status (like my Grandmother’s sequin-covered electric wheelchair). Technology is cultural: those who own and control a technology define a social class.

- Companionship: Robots – especially software robots like the ones we make at Geppetto – also offer companionship, mental exercises, conversation, guidance, and advice on health-related issues from pharmaceutical to dietary information. This companionship also includes to-do lists for bathing, laundry, cleaning, cooking, feeding, food shopping, pharmacy visits, etc. This companion can keep track of certain health data like blood test results and blood pressure, weight, height, temperature, etc. Integration with peripherals like Apple and Samsung offer an easy step for such open APIs. And then there’s the custom data, non-normative data, and personalization and customization that these systems can learn.

Call them slaves or companions, but robots are there to give help when people can’t.

Robots can amplify what healthcare providers already do well

Robots aren’t replacing us. They’re complementing us.

None of the above-mentioned aspects of surveillance, privacy, or social status threaten the jobs of healthcare providers. Robots, like personal computers, amplify what we can do. We can look to factories to see the future of healthcare. Human-robot collaboration will allow us to increase not just our knowledge management, but also our efficiency. Just look at how BMW and VW are exploring the ways in which robots can work alongside humans improve the quality of our work.

That electric wheelchair we got for my Grandmother was the 1990s equivalent of a robot: it was a modern, electric prosthetic that helped both her and us. It helped her get around and it helped us help her to be independent. We did not overturn our relationship with her because we were no longer physically carrying her. In fact, we helped her to be prouder, more independent, happier, and more competitive at games of bridge. She was proud to have this icon of social status, her Greta Garbo image, she was proud to show that her family supported her, and she was able to be more herself with the help of this electrical prosthetic, covered as it was in sequins.

For now, we’ll have to see how the designers, payers, providers, and nursing centers apply this technology, and hope that the dialogue is able to take a more moderate tone. At least until the ChildCare robots are introduced – then we’ll really see the flame wars. Maybe the robots themselves will contribute to the dialogue by then.

tags: c-Health-Medicine, cx-Politics-Law-Society, human-robot interaction, robots for eldercare