Robohub.org

Should both the successes and failures of space robots curb the ambition of a manned Mars mission?

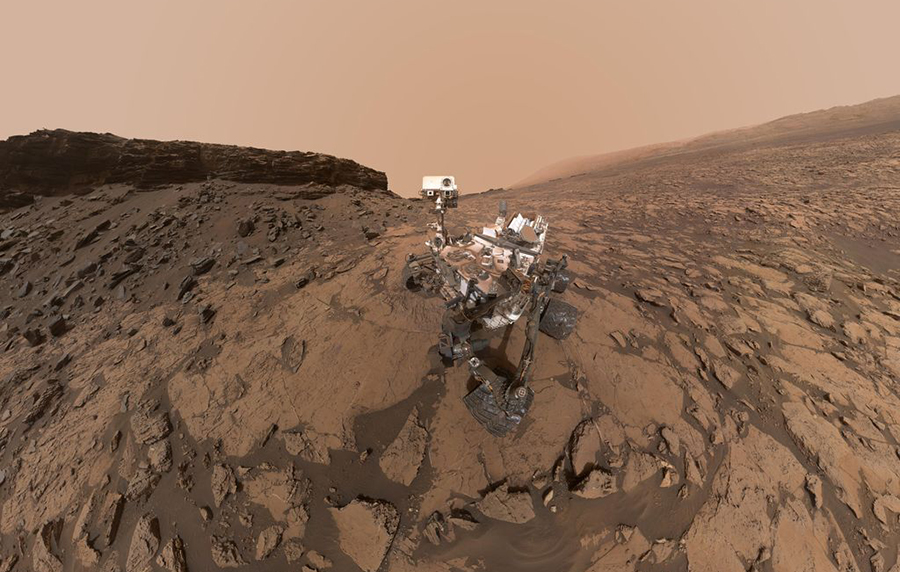

This self-portrait of NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover shows the vehicle at the “Quela” drilling location in the “Murray Buttes” area on lower Mount Sharp. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

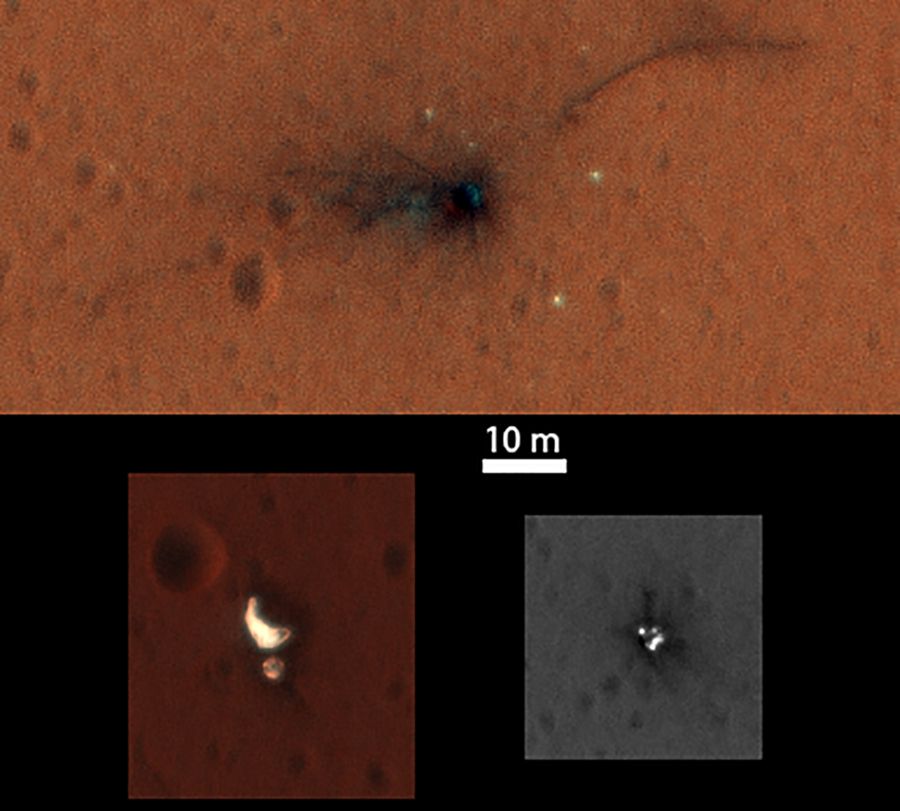

Late morning, red skies over Mars, and the first human interloper emerges from her landing craft to review the dusty expanse. As she eases carefully down the ladder towards the alien earth, her mind spins with the words that, like Armstrong’s, will echo forever in the human conscious. She speaks and, when her signal reaches home just over three minutes later, 11 billion hearts skip a beat. It’s a powerful image, oft perpetuated in such media as the upcoming National Geographic “global event series” MARS. But below is another, far realer image: the crater left by Schiaparelli after its parachute jettisoned too early and it ploughed into the Martian surface, fatally. Images like this illustrate the truly difficult, dangerous and costly business of spaceflight.

Losing robots is dramatically less costly—both existentially and financially—than losing humans, hence the push to design robots here on Earth capable of performing in harsh environments considered to pose an unsatisfactory risk to humans. But when it comes to the globally harsh environment of Mars, we tend to accept unanimously, axiomatically, that the end goal must be to send humans to conquer it, and soon! Advocates of a Martian human spaceflight goal—such as Elon Musk, Explore Mars Inc, and The Mars Society—are pushing for a human presence on the Red Planet by the 2030s, arguably underestimating the difficulty of achieving such a horizon in just two decades, and offering little to no justification for colonization other than the vague hero myth of manifest destiny. At the very least, if we’re to send our covered wagons rolling and ruining across a new celestial frontier, should we not first qualify why the $1010 it’d likely cost wouldn’t be better spent on further robotics-lead research missions?

The massive achievements of humanity’s still primitive and variable robot explorers have surely justified continued funding over infinitely more complex manned missions. Could a human have done such a better job than Curiosity, Spirit or Opportunity, so as to justify the inordinately higher risks? And what could more multifaceted, technologically advanced robot explorers achieve on humanity’s behalf, given time and funding? And whether they’re successful in their missions, or rain down like silvery chaff from the thin, Martian skies, the lessons we learn are invaluable. It’s never too soon for robots. And it’s always worth the risk. Can we say the same about human spaceflight missions?

Closer to home

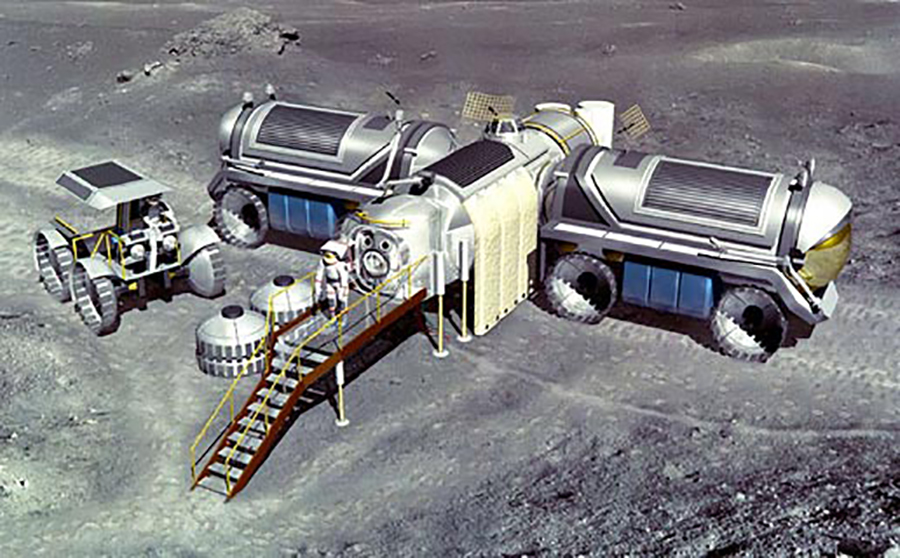

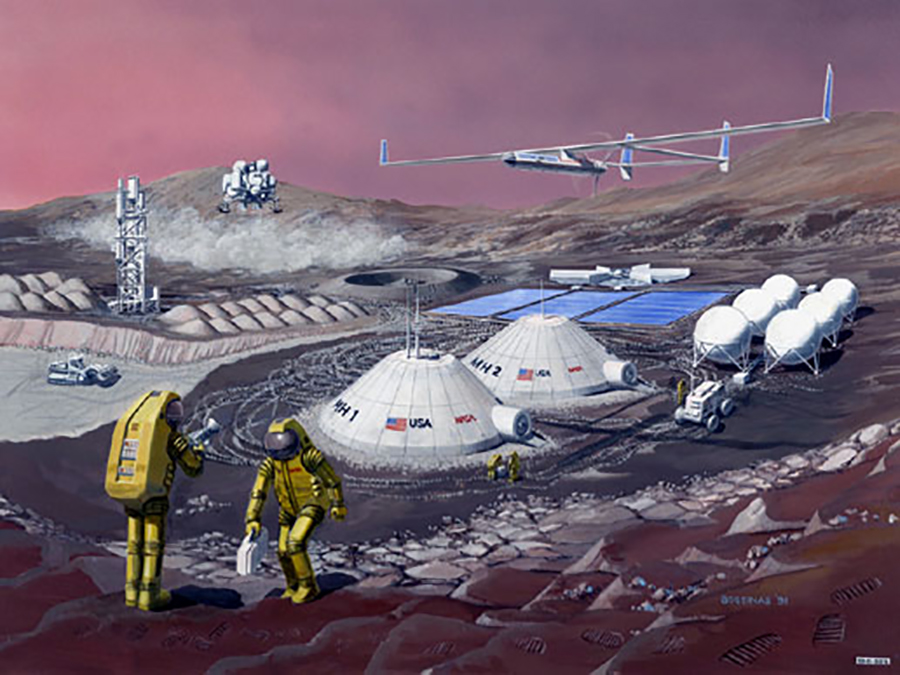

Preferring also to focus on the horizon goal of humans on Mars by the 2030s, NASA currently has no plans to return to the moon. Or so we thought. However, at the end of October this year, NASA announced it was “seeking information from potential partners” who were interested in designing small robotic payloads that could be launched and sent to the surface of the moon within a 2017-2020 timeframe. NASA’s primarily interested in understanding how future missions to Mars might use robot technology to generate resources like water and oxygen, create usable fuel for spacecraft, conduct in-space and extraterrestrial manufacturing and construction, and other operations relevant to making a future Martian colony work. It’s clear NASA see the moon as a mere technological proving ground, a springboard to Mars. But other experts in the field (even at NASA) argue for something a little more permanent on the Lunar surface.

Commenting in a recent Popular Science article, NASA astrobiologist Chris McKay concluded: “We’re not going to have a research base on Mars until we can learn how to do it on the Moon first.” He pointed out how new technologies here on Earth, such as self-driving cars and waste-recycling technologies, can make establishing a Lunar colony cheaper and more achievable than ever before. Taking the time and resources to first establish a permanent moon base might push back the timeline for manned Mars missions, but offers a multitude of advantages in the long run: it’s a cheaper, safer, more achievable goal, closer to home, that can potentially offer a blueprint to how human-robot interaction might evolve outside of Earth’s protective shield. It’d be a big deal to see human’s living on the moon. Equally, wouldn’t it be a big deal to see the first robot manufactured on another planetary body?

Together forever, as one

I’m not saying that humans should stay Earthbound forever, never leaving for Mars. I’m simply advocating a deeper, more informed conversation. Let’s not run 225 million kilometers away before we’re ready. Let’s set achievable, affordable goals and learn all the lessons we can from our robot partners, our canaries in the coal mine.

But I get it. I’m pooping the party aren’t I?

I can empathise with the visceral, reflexive response I provoke in fellow enthusiasts—akin to chewing on sour cud—when I allude to the notion that humans shouldn’t necessarily emigrate to a dead and deadly desert planet just yet. I too was raised in the West by “the greatest generation”, and their “baby boomer” offspring, to whom human spaceflight was far more personal, less justified by scientific enquiry and more inspired by geopolitical, socioeconomic factors. The cardboard-box suited astro-child in me gasps, enthralled at the thought of humans living on Mars. Ah, the wonder, the excellence of the human spirit…

But that isn’t a rational response. What’s rational is weighing realist human spaceflight goals against what can first be achieved with cheaper, expendable robot alternatives. Should we not curb our enthusiasm, our collective delusion of achieveability, and concentrate on paving the way, gradually, for more established and long-lasting spaceflight architecture? Or, to a greater extreme, could and should humanity’s lasting impression on the Universe be not boot prints in dust and regolith, but the intrepid robot ambassadors we created and sent forth to better our understanding of ourselves?

If you enjoyed this article, you might also be interested in:

- Schiaparelli, are you there? The high risks of space robotics again crash home

- Drone learns to see in zero-gravity

- Robots Podcast #217: LunaRoo, with Jürgen Leitner

- The four coolest NASA robots

- Exoskeletons: From helping people walk to controlling robots in space

- NASA Space Robotics Challenge prepares robots for the journey to Mars

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: Mars, Space