Robohub.org

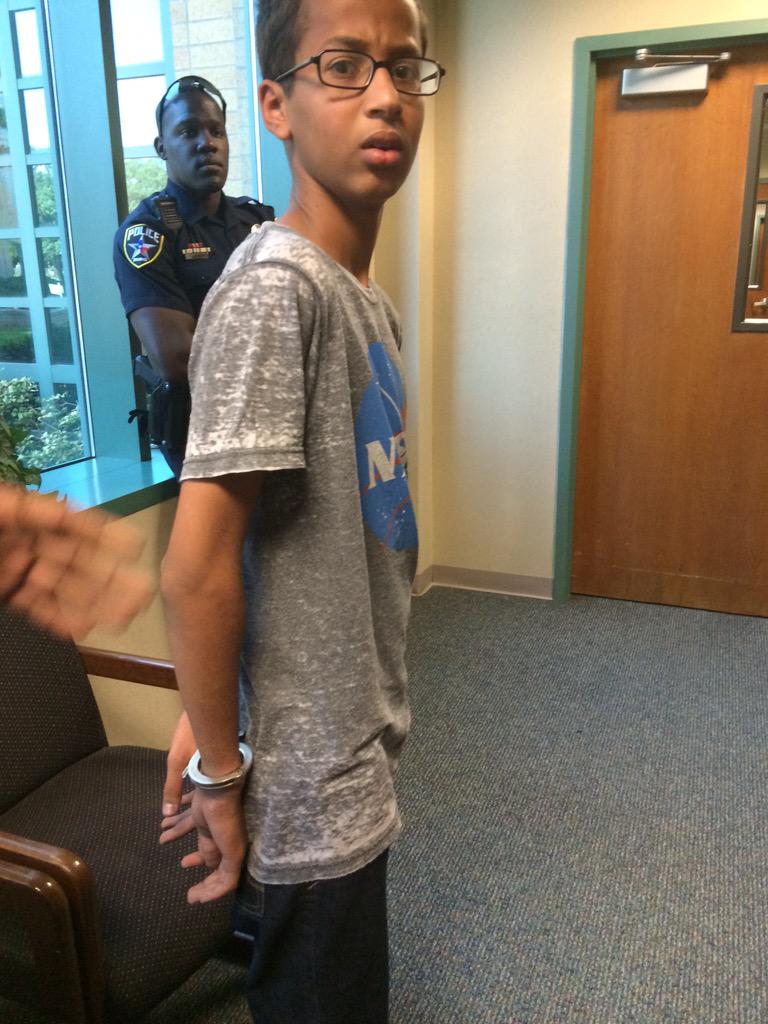

Let’s hope that #IStandWithAhmed will help improve diversity in robotics

If you’ve been following the twittersphere you’ve heard the story of Ahmed Mohamed, the 14-year-old boy who was arrested after the digital clock he built to impress his highschool teachers was mistaken for a bomb. There has since been a large public outcry and outpouring of support for Mohamed, whose story prompted invitations by US President Obama to visit the White House, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to visit Facebooks’ headquarters, as well as invitations from MIT and NASA. This is a great story of the science community rallying behind one unjustly accused boy, but what of the many young students from outside the ‘mainstream’ population whose creativity and proclivity for science flies under the radar, or worse, who never bother to study STEM subjects in the first place?

Public rallies of support may promote good feelings, but they do not necessarily effect change. Take the movie Spare Parts, for example. The movie was based on the true story of a group of illegal immigrants from Mexico who built an underwater robot for a NASA-sponsored robotics competition, and against all odds won. “When the movie ends in 2004, their future is bright,” said a NTY op-ed titled The Cruel Waste of America’s Tech Talent by Joshua Davis, author of the book on which the movie was based. “Unfortunately, that’s not how the story really ends.”

Davis goes on to describe the fate of the boys on the winning team: “After the event, lower ranked contestants went on to rewarding jobs at tech companies and research institutes. Meanwhile, the Carl Hayden students struggled to afford tuition for college.”

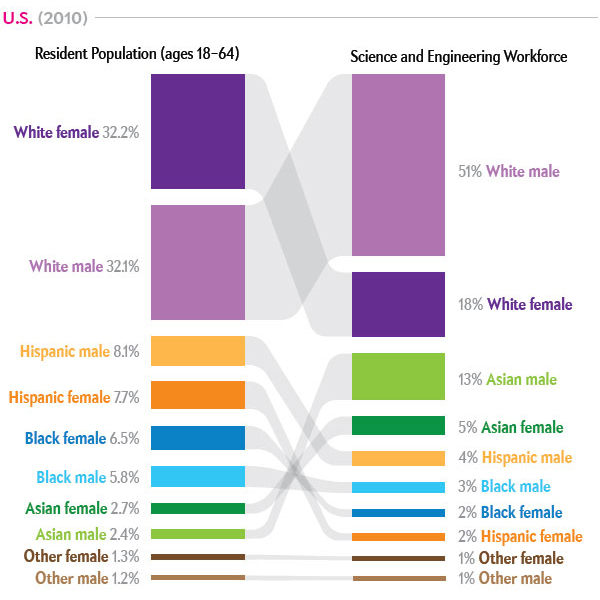

The STEM fields in general, and robotics in particular, have a miserable record for diversity. Despite commendable efforts to change that — including initiatives like AFRON‘s ultra-affordable educational robot challenge, TechBridgeWorld, and ICRA’s historic all-female organizing committee in 2015 — tangible evidence of progress is difficult to find. One need only attend a conference or trade show to see that diversity in robotics is severely lacking.

Source: Scientific American. Diversity in Science: Where are all the Data?

There are many reasons why this matters, and to name them all here only gets us caught in the hamster wheel of justification. Can’t we get past that? Put simply:

Diversity matters because the future genius behind the next big development in robotics might just have been belittled out of the field by an insensitive elementary school math teacher, or frustrated out of a career in robotics by the proverbial glass ceiling. There is just too much intellectual capital at stake — and too many research problems to solve — to ignore the issue.

How can we broaden participation in the field?

First, data matters — because without it we have nothing to measure our progress against. True, there are studies on diversity in STEM (such as this NSF report) but there is little information out there about how many women, minorities and people with disabilities participate specifically in robotics education and employment. Meanwhile, though evidence suggests that while diversity in the broadly defined sciences is slowly improving, it may in fact be reversing in fields like engineering and computer science (e.g. the number of computer science degrees in engineering dropped by 12% between 1991 and 2013). What is responsible for this downward trend? How does this map onto the field of robotics? Finer grained tracking of participation in the field at the government and institutional level would set a baseline against which to measure progress, and could help shape educational policies to encourage more people of differing backgrounds to enter, and stay in, the field. (If you are looking for evidence, however, a great start can be found in this post by Andra Keay.)

Mentorship — It’s difficult to overestimate the value of mentorship, and its effects are catalytic when it happens at a variety of levels: at the student/peer group level, with ones’ parents and school teachers/professors, and reaching up to the highest levels in academia and business. How many young people were inspired to pursue a career in robotics when Will.I.Am from the Black Eyed Peas gets onstage at a FIRST competition to rally the students? How many young women were encouraged by seeing the women of ICRA’s 2015 organizing committee at the tops of their careers?

Collaboration — Consider the huge range of application areas that robotics is trying to address, and the fact that many of these applications are either specifically designed for or highly relevant to the very communities that are underrepresented in robotics: exoskeletons and robotic prosthetics for the disabled, robots for removing landmines in war torn countries, or drones that monitor drought conditions in subsaharan Africa or deforestation in the Amazon, to name a few.

Does it not make sense to develop technology solutions in conjunction with these communities? In the words of Bernadine Dias, founder of TechBridgeWorld, the key is “changing technology to fit communities rather than forcing communities to change to fit technology.” This is how innovative initiatives like Cybathlon – a competitive sporting event that teams disabled athletes with teams of roboticists to develop advanced assistive devices — take root. And they are all the more powerful when the end-users themselves are directly involved in the research, such as the work being done by Kavita Krishnaswamy in collaboration with Tim Oates on robotic assistive devices for people with severe disabilities.

Funding — Bernadine Dias said that the biggest lesson she has learned working with developing and disadvantaged communities is “how incredibly resourceful people are. We travel the world and we work with communities where I just cannot imagine what I would have done in that situation, and they come up with very brilliant ways to do things.” Similarly, AbdulAziz wrote about to us about the obstacles he faces as he builds a robotics ecosystem where none currently exists, but he also about his advantage: “low developing and operation cost.”

Yet whether it’s about supporting a local hacker space for inner city kids, or doing field research in a developing region of the world, at the end of the day it all comes down to funding. Expertise costs money, and paying for people’s time is difficult when resources are limited. Even a volunteer’s travel costs can be insurmountable. In this way, lack of funding also undermines efforts in mentorship and collaboration. And while seed funding can get exciting projects off the ground, it’s the decidedly unsexy sustained funding for long term operating costs that are mostly like to make a difference in the end.

Jonathan Ledgard, Director of Afrotech, a future Africa initiative based at EPFL tells us that “Inventiveness often comes from the margins, but we need to invest much more seriously in the tools that allow for inventiveness, which is why ultimately a Facebook Internet providing drone over Burundi with free access to astrophysics MOOCs may have more effect than any gestures.”

The elephant in the room

Ahmed Mohamed’s school board stands behind its original response to the ‘bomb’, stating that “Out of an abundance of caution, we had to take action.” The latest development in the story is that Mohamed’s parents are reportedly withdrawing him from the school. This is to be expected: the fury of attention and the divisiveness would be overwhelming to anyone at this age. Most teens would rather fit in than be the centre of a national controversy.

It may come as a surprise, but for some, Ahmed’s story is familiar. Mahmoud AbdelAziz, founder of EG Robotics and coordinator of the Minesweepers competition for developing de-mining robots in war torn regions wrote to tell us that: “Ahmed’s issue, for me, is a normal situation. Through the robotics competitions I organize in Egypt, I know many students who faced the same situation due to lack of knowledge from the police.” (You can read about his fascinating efforts to build a robotics ecosystem in Egypt here.)

Personally, I have heard organizers of other competitions describe the difficulty foreign teams can face trying to bring equipment and people over borders, and professors describe their frustration at having their students’ visa applications rejected when they have applied to attend a conference in order to present their first paper — a critical milestone for any young academic.

These stories and Ahmed Mohamed’s share a common theme: they are not so much about ‘ignored potential’ as they are about ‘potential perceived as threat’. Would Ahmed have been arrested if he were a nerdy white kid? What these stories remind us is that racial stereotyping is not just career limiting in an abstract sense.

The handcuffs make it all too real.

Many thanks to the Robohub core team — especially Andra Keay, Sabine Hauert and Yannis Erripis — for their help shaping this essay, as well as Mahmoud AbdulAziz and Jonathan Ledgard for generously taking the time to share their thoughts.

tags: c-Politics-Law-Society, robohub focus on diversity