Robohub.org

Snake-inspired robot uses kirigami to move

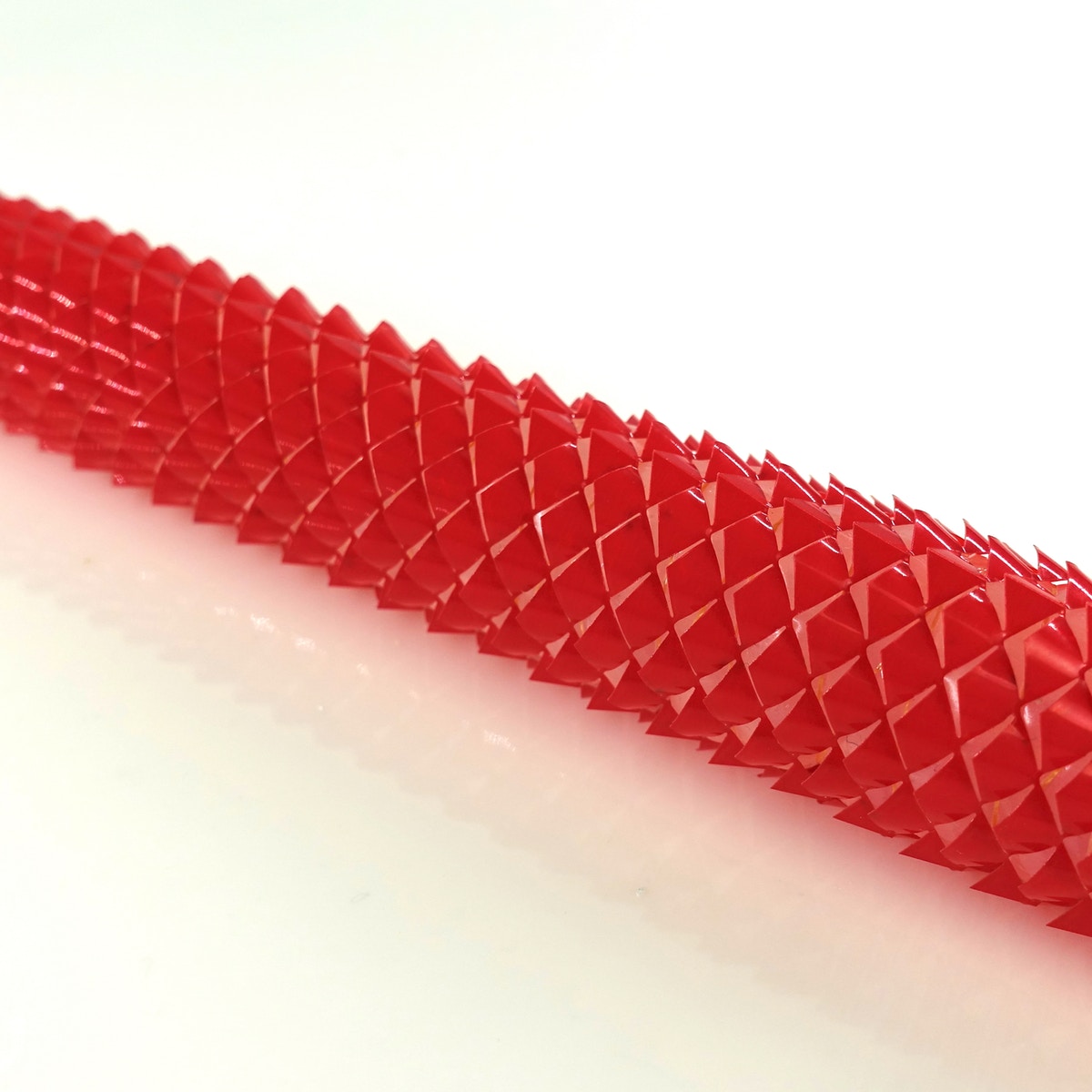

This soft robot is made using kirigami — an ancient Japanese paper craft that relies on cuts, rather than origami folds, to change the properties of a material. As the robot stretches, the kirigami is transformed into a 3D-textured surface. Credit: Ahmad Rafsanjani/Harvard SEAS

By Leah Burrows

Who needs legs? With their sleek bodies, snakes can slither up to 14 miles-per-hour, squeeze into tight spaces, scale trees, and swim. How do they do it? It’s all in the scales. As a snake moves, its scales grip the ground and propel the body forward — similar to how crampons help hikers establish footholds in slippery ice. This so-called “friction-assisted locomotion” is possible because of the shape and positioning of snake’s scales.

Now, a team of researchers from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University and the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) has developed a soft robot that uses those same principles of locomotion to crawl without any rigid components. The soft robotic scales are made using kirigami — an ancient Japanese paper craft that relies on cuts, rather than origami folds, to change the properties of a material. As the robot stretches, the flat kirigami surface is transformed into a 3D-textured surface, which grips the ground just like snake skin.

The research is published in Science Robotics.

“There has been a lot of research in recent years into how to fabricate these kinds of morphable, stretchable structures,” said Ahmad Rafsanjani, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS and first author of the paper. “We have shown that kirigami principles can be integrated into soft robots to achieve locomotion in a way that is simpler, faster, and cheaper than most previous techniques.”

The researchers started with a simple, flat plastic sheet. Using a laser cutter, they embedded an array of centimeter-scale cuts, experimenting with different shapes and sizes. Once the sheet was cut, the researchers wrapped it around a tube-like elastomer actuator, which expands and contracts with air like a balloon.

When the actuator expands, the kirigami cuts pop out, forming a rough surface that grips the ground. When the actuator deflates, the cuts fold flat, propelling the crawler forward.

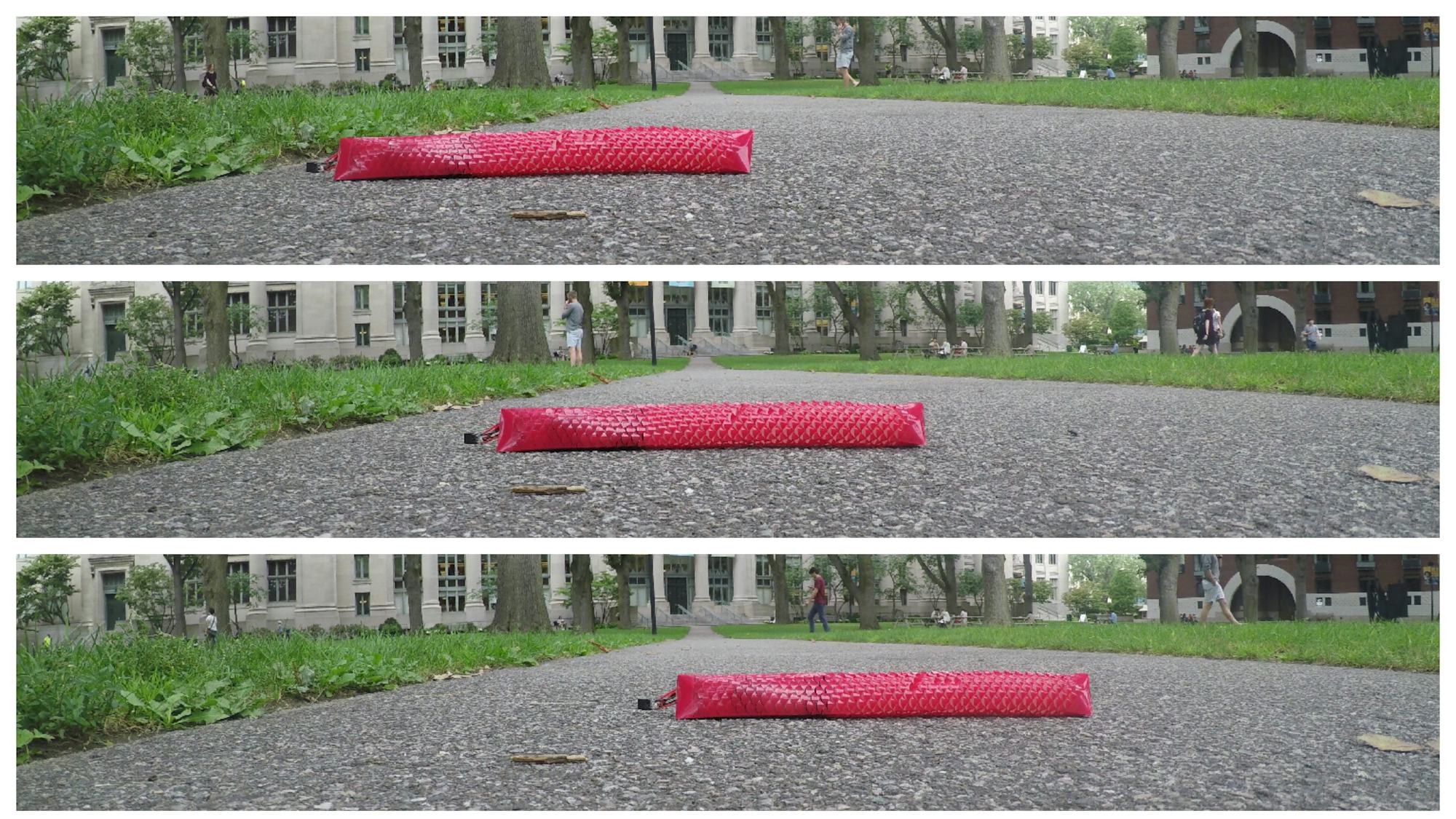

Wyss and Harvard researchers have built a fully untethered, soft robot, with integrated on-board control, sensing, actuation and power supply packed into a tiny tail. Credit: Ahmad Rafsanjani/Harvard SEAS

The researchers built a fully untethered robot, with its integrated on-board control, sensing, actuation, and power supply all packed into a tiny tail. They tested it crawling throughout Harvard’s campus.

The team experimented with various-shaped cuts, including triangular, circular, and trapezoidal. They found that trapezoidal cuts — which most closely resemble the shape of snake scales —gave the robot a longer stride.

“We show that the locomotive properties of these kirigami-skins can be harnessed by properly balancing the cut geometry and the actuation protocol,” said Rafsanjani. “Moving forward, these components can be further optimized to improve the response of the system.”

“We believe that our kirigami-based strategy opens avenues for the design of a new class of soft crawlers,” said the paper’s senior author Katia Bertoldi, Ph.D., an Associate Faculty member of the Wyss Institute and the William and Ami Kuan Danoff Professor of Applied Mechanics at SEAS. “These all-terrain soft robots could one day travel across difficult environments for exploration, inspection, monitoring, and search and rescue missions, or perform complex, laparoscopic medical procedures.”

This research was co-authored by Yuerou Zhang; Bangyuan Liu, a visiting student in the Bertoldi lab; and Shmuel M. Rubinstein, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Applied Physics at SEAS. It was supported by the National Science Foundation.

tags: herotagrc