Robohub.org

Adjust how you learn and quickly pick up robotics programming

“The biggest obstacle preventing robotics going mainstream is not having good programmers able to program robots,” Brian Gerkey, CEO of the Open Source Robotics Foundation.

Learning to program robots is difficult.

I mean, real robots.

I am not talking about learning to program Lego and the like. I’m talking about making a Reem robot move around a shopping mall helping people to carry their bags. Or a Fetch robot cooperate on a warehouse with humans helping them to fetch the packages.

Yes, programming of these robots is difficult.

In order to simplify the programming of those robots, frameworks have been created:

Those are the real thing. They are frameworks that are installed in real robots and used to make them work. I’m not talking about using Matlab for programming your algorithm in a robot. Matlab is not used in real life, only in academia for non-replicable results. Here we are talking about the real thing.

But don’t be get me wrong. Even if those frameworks are quite complex, anybody can learn to program robots. The question is: how long does it take?

Why does it take so long to learn how to program robots?

We have identified a series of problems that prevent quick learning of robotics.

You don’t have access to robots to play with

There are many different robots available and they are really expensive. Acquiring, maintaining, and explaining the hardware are real problems that limit class size and the learning experience of the students.

As Nikolaus Correll, Rowan Wing and David Coleman indicate in their paper, A One-Year Introductory Robotics Curriculum for Computer Science Upperclassmen:

Only a subset of the course material of a robotics curriculum can be assessed conceptually or mathematically. Demonstrating a thorough understanding of an algorithm requires implementation. Unlike purely computational algorithms, which can be assessed automatically using test-input, authentic assessment scenarios are difficult to create for a robotics class.

Hence, students can hardly practice what they are learning.

We strongly believe in the CONSTRUCTIONISM approach. Defined by Seymor Papert around 1980, the constructionism approach advocates for learning by making. That is, you are not learning when somebody is teaching you, but you are learning when you practice.

If you don’t have a robot to practise with, you cannot learn properly and at full speed.

Concepts are complex to understand

The concepts of learning how to make a robot work are complex (how to make a robot grasp, how to build a navigation program, how to make it reason, etc.), which makes the learning curve very steep.

How many of you out there use ROS? Ok, how would you explain ROS to others who know nothing about it? Difficult, isn’t it?

The most meaningful unit in robotics for a newcomer is making the robot do something. Given the student’s program to make the robot do something, the robot either does it or not. This is very clear to understand. You push this button and the robot does that (or not, if you have a failure in your program). The feedback of your performance is very clear and straight.

It is not the same to get the feedback about the robot doing an action than to do it because the compilation said you forgot to include something in the CMakeLists.

The longer it takes to associate the errors with the result in the robot, the more difficult it is for the student to close the loop of understanding, and hence, learn why or why not this works that way. This is the concept of delayed reward. The longer delayed reward, the more difficult to understand the relation cause-effect and the longer it will take to learn the concept associated.

The challenge is then to provide such feedback very quickly, even if there are many steps and concepts involved in a robot action. Hence, teaching materials cannot start by indicating how to install everything, how to compile, or how to create a download new packages.

Nobody needs to know the definition of ROS to start using it. It is not a good idea to start teaching ROS by defining what a package is, or what a workspace is, then how catkin works, then what is the ROS_MASTER_URI, etc.

All of those are important, but not at this early stage. Going at that pace will take ages to make the robot do something, and for the student to understand.

Documentation made by teachers for teachers

We found that documentation, tutorials and classes are made by people who already know robotics for people who already understand robotics. I call these type of tutorials reference tutorials. Those tutorials basically start by describing concepts one-by-one, following a hierarchy of well-defined definitions by people who already understand the subject. If you ask the reason of that concept or for what do you need it, they will tell you that you will understand later (but later is too late!).

Generally speaking, robotics is sometimes taught as if it were for the instructor. It is very structured with a clear concepts hierarchy. It is a problem that documentations of robot programming frameworks work as a reference tutorial for the engineers that wrote it. Of course, you can learn from those but it is a lot harder and much slower (I learnt ROS that way).

I do believe we do not work this way. One thing is the way we structure information once we know the whole space, and another is the way we structure it when we are learning. Very different things.

The solution we propose

The method we propose is to make the students forget as many concepts as possible and concentrate on doing things with the robots. Complex concepts will be taught later when the student has the base. This approach is based on how we learn and not in how we order our thoughts once we have them.

We propose a solution to speed the learning that provides the following steps:

1. In media res. That is the trick Star Wars used to make the movie more appealing (new Star Trek movies have copied successfully, I think).

This means, start in the middle, not the edges. The idea is to put the student in the middle of the knowledge to learn and make it move to the sides, discarding a lot of things in the way to the side.

2. Learning by doing. Not by reading or by typing, by working on a robot.

This is the successful case of Code Academy. There you can learn to code by doing and quickly observing the result of what you have done.

We must have the same type of environment for robotics learning. Do, then observe on the robot the result of your program.

3. A step by step guide. Showing only what is required for the next action of the robot, and removing out of the equation what is not required/useful at that specific learning moment (even if important for the success of the step).

For example, you must have a catkin_ws in order to launch a ROS package, but we do not believe that we must explain to a new student how to create a catkin_ws. Instead, we provide it done ready to be used, and once he becomes used to it, then we show how to create your own.

Implementation

At The Construct, we have integrated all those ideas into a platform that allows students to quickly learn (in 5 days) any concept of robotics programming. I mean, for real robots!

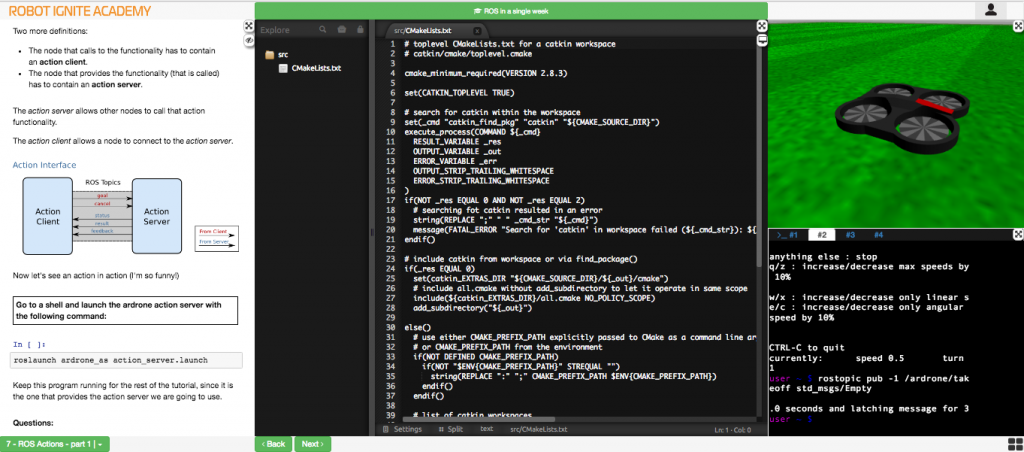

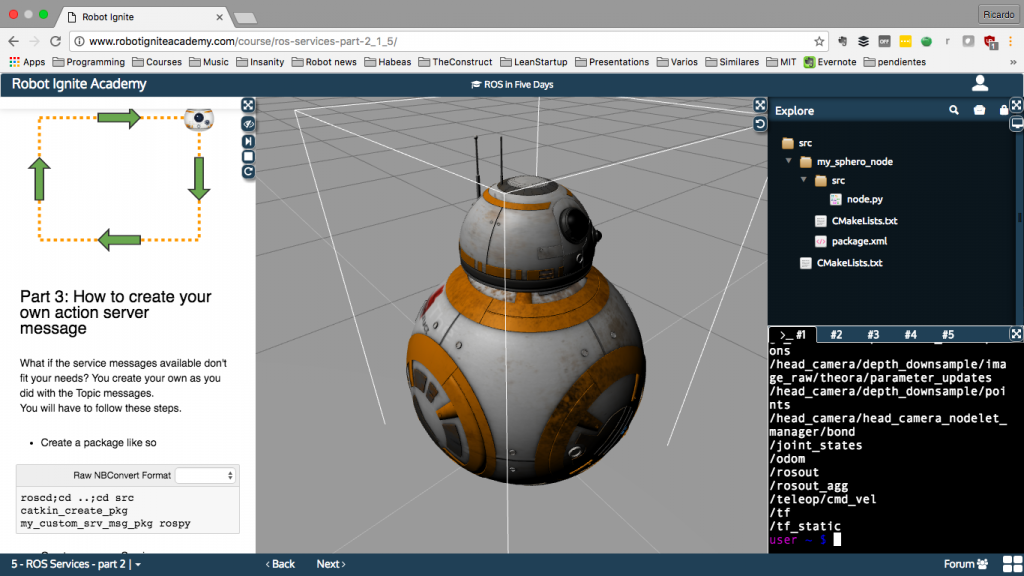

Our platform is called Robot Ignite Academy, and we like to call it the Code Academy for Robotics. We integrated step by step explanations with a robot simulation and program development environment, everything inside a web browser (hence you can learn using any type of device).

At Ignite Academy, students will learn complex robotics concepts by:

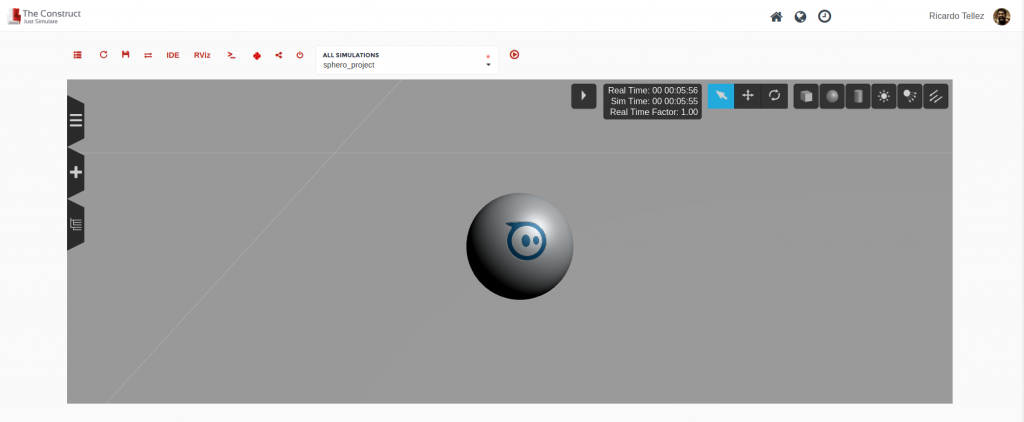

- Using simulations of the real robots. Many. Examples include Turtlebot-2, Husky, Sphero, Wam, quadcopters… even BB-8! Students use a simulation of the robots as if they had the robot.

- Use a step-by-step lesson process that engages the student on doing something with the robot after every step, in order to check that he is understanding the explanation.

- Use the description not only to explain, but also to do. Include interactions in the explanation. For example, generate graphics dynamically on the explanation based on what the robot is doing at that moment.

- Forget about certain basic concepts (for example, what is ROS… who cares? You don’t need to know what is ROS in order to use it and make a robot work) We believe that once you have mastered the real thing, getting those concepts will be easy peace. But if you put them on the pile of things you have to learn together with the others, it makes the whole thing difficult to swallow.

All that without having to install anything in your computer, and with simulations at the core of the learning system, not only as something additional.

In our system, the simulation is at the center. We provide different simulated robots that the student has to practice with. They use simulation as if they had the real robot, with the difference that they don’t have to care about building it. It is just provided and ready to be used.

Conclusion

We are providing the Ignite Academy platform online, for anyone. Students can use it for their personal learning. Teachers can use it for teaching during the class. Companies can use it to upgrade their workers.

What is also important to state is that you don’t have to care about installing anything. Connect using a web browser from any type of computer and start learning.

tags: c-Education-DIY, The Construct