Robohub.org

Octopus points to the future for keyhole surgery

by Rex Merrifield

by Rex Merrifield

Keyhole, or minimally invasive, surgery can offer many benefits over more traditional, open operations, including reduced risk of infections, quicker recovery times and less scarring. But internal organs can get in the way when hard robotic arms are used, given that access can be very limited and soft tissue can sometimes move in unexpected ways.

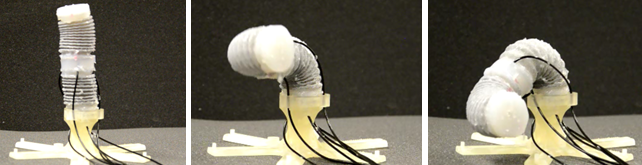

The EU-funded STIFF-FLOP project has designed, built and operated a soft robotic arm that can squeeze into the body, manoeuvre gently around soft tissue, reconfigure itself, and stiffen to perform tasks that need force.

‘The aim is to develop soft robotics systems that can elongate, bend and move around organs,’ said project coordinator Professor Kaspar Althoefer who conducted the research at King’s College London, UK, and is now at Queen Mary University of London, UK.

‘The octopus provided some inspiration. It has no bones or skeletal structure, and it can squeeze through very narrow openings, but stiffen when required,’ he said.

The robotic arm works through a combination of air and granules. When air is pumped in, the granules inside it are able to move freely and allow both flexibility and a large range of motion. When the air is sucked out again, the granules clump together, making the structure stiff and rigid in the required position.

The system also helps surgeons to deal with complex soft tissue movements and uncertain situations, such as when organs shift, or move with the patient’s breathing and heartbeat.

With keyhole surgery, the instruments are inserted through narrow openings and they have to pivot around that small incision. And because the surgeon is unable to use a hand directly to feel inside the body, for example to identify the borders of a tumour, a successful operation is dependent on visual feedback from a camera at the end of the robotic arm.

Researchers have developed a prototype of an arm that can stiffen or become flexible on demand. Image courtesy of StiffFlop

So among the next steps is developing technology allowing surgeons to receive feedback from the operation site through touch, a field known as haptics.

In addition to joysticks and data gloves, haptic devices include possibilities such as vibratory actuators and pressure pads on the surgeon’s arm to simulate the feeling of operating through a much larger incision.

Dr Helge Wurdemann, project manager of STIFF-FLOP, said: ‘In particular, haptics has great potential to offer benefits to surgeons but, more importantly, to patients’ outcomes, when it comes to interventions that are less and less invasive.’

Cadaver

The STIFF-FLOP project put the soft robotic arm through a series of successful tests on a cadaver. The collaborators are now developing it further, with a view to possibly testing it in veterinary surgery, and eventually in operations on live people.

‘We have demonstrated the feasibility of the approach and so we would like to try it out on a living system, though that will require much further development,’ Prof. Althoefer said.

Other EU-supported researchers have been working to improve the software that controls surgical robots and tools such as graspers or scalpels and provide the surgeons who use them with the sense of touch when tissue is palpated, grasped or cut.

‘Any kind of design choice, any kind of device, any new control system, has to be grounded in what we as motor neuroscientists understand about how people control motion and perceive information,’ said Dr Ilana Nisky, senior lecturer in the Department of Biomedical Engineering and head of the Biomedical Robotics Lab at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel.

It can squeeze through very narrow openings, but stiffen when required. Professor Kaspar Althoefer, King’s College London, UK

‘From the side of the surgeon, we are developing the software that will make them feel as if they are present there, so that it is really natural,’ added Dr Nisky, whose TELEPRESENCE SURGERY project has been developing new control software for existing robotic surgical equipment.

Her research has found that very experienced surgeons operating with robotic equipment use a far greater ‘toolbox’ of hand and arm movements in carrying out operations than novices do. While experience obviously brings increased skill, the contrast was much bigger than expected and was present even in the performance of very basic motor tasks that do not require surgical knowledge. Those findings provided inspiration for further developments in robotic arms and controls.

‘We hope that eventually robots will make it easier to learn how to use them too,’ Dr Nisky said. ‘Lead surgeons can do marvellous things with the robots, and by improving the controls and systems we hope that will shorten the learning curve for novices and they will be able to master complicated procedures faster.’

More info:

tags: c-Health-Medicine, cx-Research-Innovation, EU