Robohub.org

The social car: Simplifying autonomous action with Thing Theory

Automating vehicles simplifies operation for humans but also increases complexity. In order to negotiate a safe journey within a crowded transportation system, cars must communicate messages not only to various parts of themselves but possibly also to other cars. Successful social cooperation requires each agent, person and vehicle to have a common view of critical information. Thing Theory is proposed as a network model that can help cars make sense of a multitude of messages.

People have had to adjust and change in response to vehicles and automation, and early automobiles were often seen as anti-social intrusions to street life. They precipitated great divides between the public, who felt they had a right to the streets, and drivers, whose speed and power gave them dominance. There were arguments about accessing public streets and attempts to resolve these conflicts through legislation to protect the public against automobiles [1].

Today, vehicles are becoming communication devices as embedded telecommunications technologies are designed into cars. Historical debates related to the automobile have been resurrected, and perceived threats to the public are being challenged just as they were in the past, such as legislation barring drivers from phoning and texting [2].

Cars and people are already part of a highly complex interrelated social system that reproduces the infrastructure they are dependent upon. Social cooperation creates and maintains the systems that enable cars to function: road construction and repair, fuel, rubber for tires, oil, glass, metal, paint, and many other industries combine to make running a car possible. However, when a driver is isolated in a comfortable car, traveling down a beautiful road, it is unlikely that they are aware of the social system cooperation required to make their driving experience possible. If we add the potential for real time (synchronous) or shifted-time (asynchronous) message communication to the driving experience, the picture becomes far more complex.

At present, humans use mobile devices to extend their capabilities and often multitask. “Divided attention” describes a common outcome when humans focus on more than one thing at a time. Research on divided attention indicates that people using mobile devices are not generally able to concentrate well on other things in their vicinity when walking or driving whilst having a conversation that requires them to process information [3][4][5].

Mobile technology supports both asynchronous and synchronous communication with short propagation delays, resulting in multiple, multiplexed communications scenarios. When factored across a group of communicating entities, the resulting set of interactions can be described as layers of partially overlapping messaging networks between any two or more entities. As social and infrastructure domains become more automated, the need for sociability will continue to increase.

An “exploded view” of a fragment of a PoSR network. Each layer represents a different social network of the same individuals, each based on a communication channel. Source: Sally Applin

We call the dynamic structure emerging from the flow of messages, transactions, and information within and between these networks PolySocial Reality (PoSR) [6]. Communications across PoSR networks exacerbate the impact of divided attention to further extremes and it becomes greatly multiplexed. Its complexity would seem well beyond the capabilities of our physiological systems. In other words, too many messages contribute to a feeling of being overwhelmed.

This may lead to message content being ignored and not responded to, sometimes to the detriment of safety. This is compounded in automated vehicles, as these will parse internal messages (system function messages) as well as external messages, in order to negotiate a safe journey within a transportation system occupied by many other vehicles. Safety strategies take time to develop and the results of poor decisions can be critical or even fatal.

Maintaining safe driving conditions in conjunction with the PoSR environment poses a complexity problem that is likely to require the intervention of artificial intelligence (AI) agents. When cars have the potential to be “social” (interacting with themselves, their occupants, and machine-to-machine) it is likely that fragmentation may occur, due to multiple, multiplexed messages sent and received at the same or different times. In hardware terms, the ability to parse multiple messages in an automobile is certainly possible. Sensors could be added to handle necessary functionality and a processor dedicated to each subsystem, thus promoting undivided attention. However, software requires further consideration.

Trusted “Agents” may help restore order. Realizing the true potential of the connected car might be possible, or at least improved, by incorporating internal systemic decision making, with reference to agency and bi-directional interaction.Thing Theory [7] is proposed as an agent-based network model that conforms knowledge of the local context of each participating Thing-agent to a common understanding by all those within a network. Thus granting them a shared contextual understanding. Each Thing-agent gains local knowledge via its relationship to people and other agents in the environment, as well as system-subagents and meta-agents in other systems. A Thing-agent is informed of the local knowledge, which is then fit to the objectives and circumstances of all participating agents.

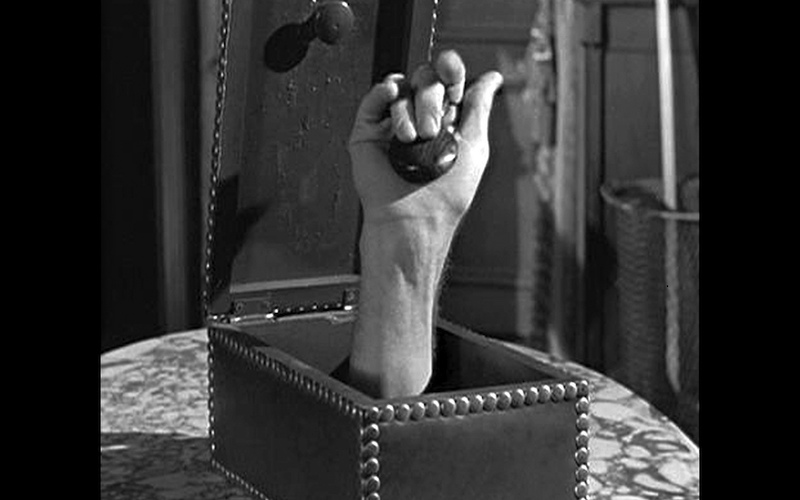

Thing Theory was inspired by the notion of the character “Thing” from “The Addams Family,” a 1960s television show based on a comic of the same name created by Charles Addams. Thing is characterized as a disembodied hand (and forearm) that has been with the family for many years and is described as both a “family retainer” and “friend.” Thing inhabits a series of tabletop boxes in different rooms of the house [8] that could be compared to a type of roughly cobbled physical network. It communicates with the family by gestures, sign language, notes, or tapping out messages in Morse code. Thing serves the family by accessing a nearby portal, in the precise room or context needed. Thing is not only a ubiquitous agent, but also an anticipatory one that migrates within the environment. The sensing, response, and location-awareness of Thing is a useful aspirational model for a network agent in a static or moving, location-aware, smart environment.

Thing functions as a communal agent, developing relationships and shaping knowledge and responses for different actors (people and sensors) within the system that it serves. While this presents privacy and security issues, the development of partial identity brokers (so we are sure who we are transacting with) and validating information (so that auto-spoofers cannot easily “hack” traffic) can ameliorate these privacy and security concerns. A Thing-agent can serve a real need to revise and design processes so that these are not so brittle, fragile, or unidirectional.

As vehicles become automated, AI will play a larger role (even replacing human drivers), it is critical to formulate a plan for handling PoSR, the complex multiplexed communications environment that emerges, and, with it, newfound forms of agency.

Thing Theory is one possible approach, that can also improve security and maintain privacy. Resolution can be achieved with two approaches. The first would be in the form of a virtual or emergent Thing-agent, (where the systems comprising each car are constructed from a constantly aggregating information feed) to create a plausible POV for other cars on the road. Alternatively, a series of literal Thing-agents belonging to the road would effectively direct traffic, replacing or augmenting current “Things” such as traffic signals, roundabouts, and road markers.

Ultimately, if nothing is done to resolve the PoSR outcomes from the complexity of automotive automation, there won’t be much movement on roads due to the inability of vehicles to cooperate with each other. If semi-autonomous and autonomous vehicles are to successfully integrate into our communications systems, there must be a way for them to communicate with other vehicles (and other humans) in a cooperative “social manner.” Thing Theory could foster this cooperation by enabling more streamlined and smarter message handling between internal vehicle communication structures, as well as with other vehicles on the road.

References:

[1] R. Kline and T. Pinch, “Users as agents of the technological change: The social construction of the automobile in the rural United States,” Technology and Culture, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 763-795, Oct., 1996.

[2] ] “Countries that ban cell phones while driving,” cellular-news.com. 2009: http://www.cellular-news.com/car_bans/ accessed 3 September 2012.

[3] S. McEvoy. M.Stevenson & A. McCartt et. al., “Role of mobile phones in motor vehicle crashes resulting in hospital attendance: a case-crossover study.” bmj331, 428 (available on-line:

[4] I. Hyman, S. Boss, B. Wise, K. McKenzie, and J. Caggiano, “Did you see the unicycling clown? Inattentional blindness while walking and talking on a cell phone,” Applied Cognitive Psychology, vol 24, pp. 597-607, Oct. 2009.

[5] D.L. Strayer and W.A. Johnston, “Driven to distraction: Dual-task studies of simulated driving and conversing on a cellular phone,” Psychological Science, vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 462–466, Nov. 2001.

[6] S.A. Applin and M.D. Fischer, “A cultural perspective on mixed, dual and blended reality,” in Proc. 16th Int. Conf. Intelligent User Interfaces – IUI’11, Workshop on Location-Based Services in Smart Environments – LAMDa’11 (Palo Alto, CA), Feb. 13-16, 2011. New York, NY: ACM, 2011, pp. 477-478.

[7] S.A. Applin and M.D. Fischer, “Thing theory: Connecting people to location-aware smart environments,” in Proc. 18th Int. Conf. Intelligent User Interfaces – IUI’13, Workshop on Location-Based Services in Smart Environments – LAMDa’13 (Santa Monica, CA), Mar. 19-22, 2013. New York, NY: ACM, 2013, pp. 115-118. DOI: 10.1145/2451176.2451228

[8] The Addams Family, “Lurch Learns to Dance,” 1964, S01E13.

This article is an adapted summary of: S. Applin and M. Fischer (2015). Resolving Multiplexed Automotive Communications: Applied Agency and the Social Car. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine (Volume 34, Issue 1), pp. 65-72.

Draft version | Full version (firewall)

More publications can be found at: http://www.posr.org/wiki/publications

tags: Automotive, autonomous driving, c-Research-Innovation, robocars