Robohub.org

The making of sci-fi adventure Robot Overlords

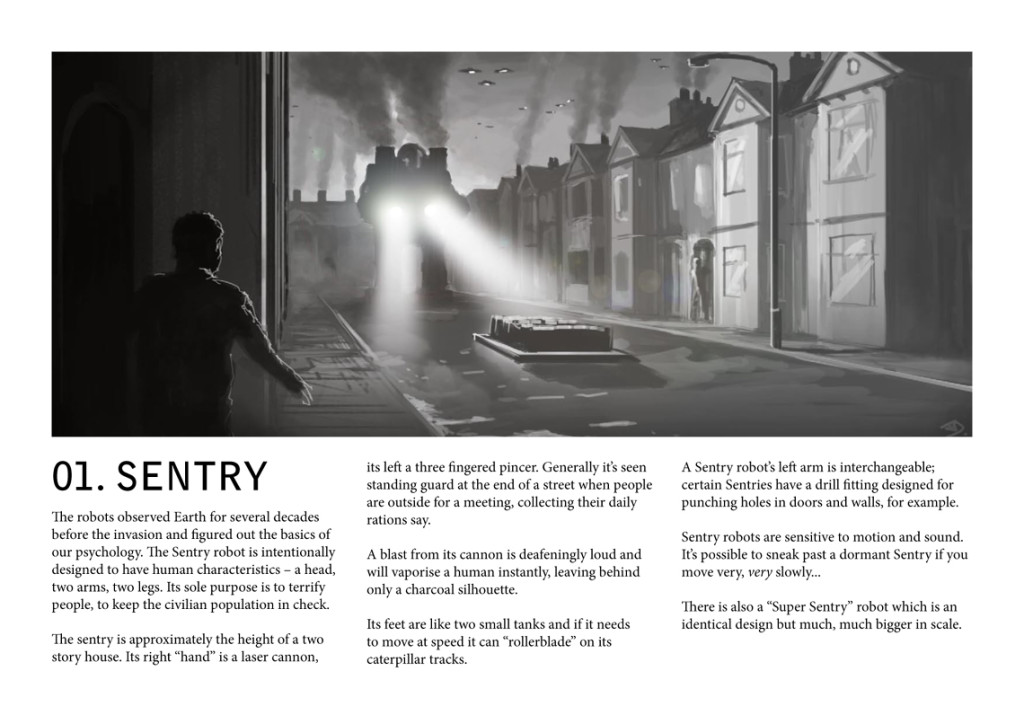

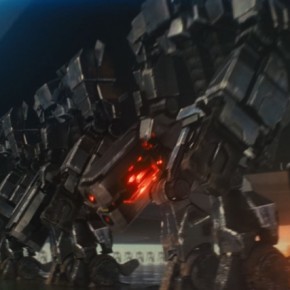

In the low-budget British sci-fi adventure, Robot Overlords, alien automatons rule the streets and ordinary citizens are locked under curfew in their homes. Just by stepping outside, you risk being vaporised by a hulking Sentry, or picked off by a lethal Sniper.

Amid the ruins of civilisation, Sean Flynn (Callan McAuliffe) leads his group of young friends on a quest to join the resistance forces that are standing against the robot invaders. Hot on their heels, however is their old teacher – now treacherous robot collaborator – Robin Smythe (Ben Kingsley) and his captive Kate (Gillian Anderson). Who will prevail? Man or machine?

Amid the ruins of civilisation, Sean Flynn (Callan McAuliffe) leads his group of young friends on a quest to join the resistance forces that are standing against the robot invaders. Hot on their heels, however is their old teacher – now treacherous robot collaborator – Robin Smythe (Ben Kingsley) and his captive Kate (Gillian Anderson). Who will prevail? Man or machine?

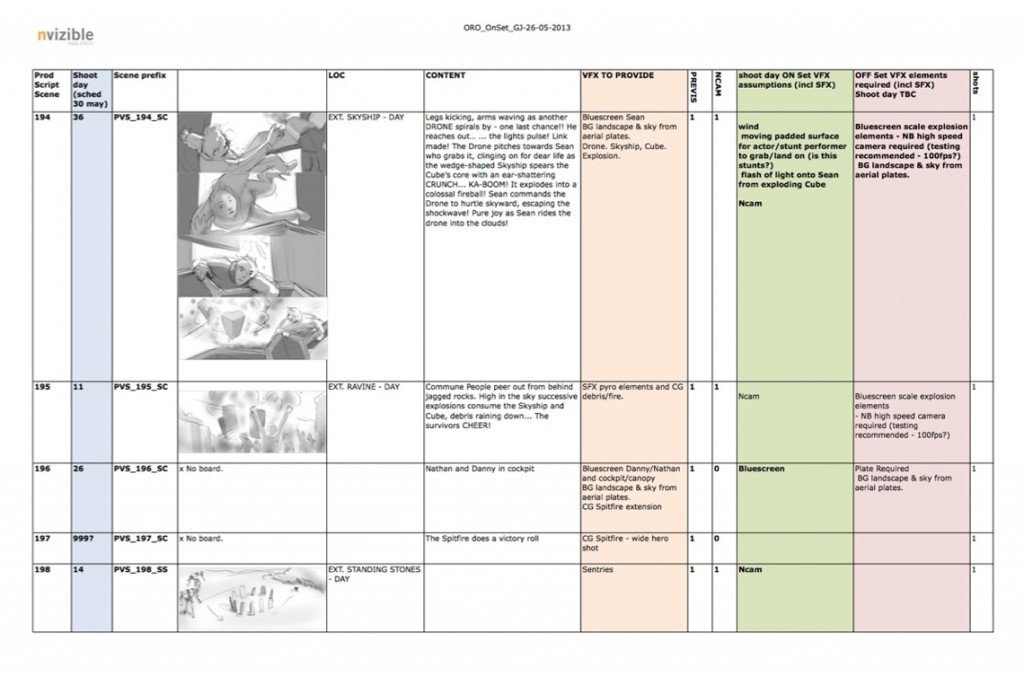

Directed by Jon Wright, Robot Overlords features some 265 visual effects shots delivered by Soho-based Nvizible, supervised by the company’s founder and co-owner, Paddy Eason. The film’s complex tracking requirements were fulfilled by Peanut FX, with additional compositing support being provided by Boundary VFX, under the supervision of Nick Lambert.

Watch a wide selection of Nvizible’s VFX shots in the official video for Robots Never Lie, written by Matt Zo for the Robot Overlords end credits

Origins of the Overlords

The original story concept for Robot Overlords came to director and co-writer, Jon Wright, in a dream. “I dreamed that I was playing cowboys and Indians with a little boy,” Wright recalled. “A huge two-storey robot came marching up the street and swung its laser cannon arm towards him, and a voice boomed out, ‘Citizen, drop your weapon immediately!’ I assumed I was just recycling a movie that I’d already seen, but eventually, I came to the conclusion that maybe it was an original idea.”

After expanding the dream concept into a two-page treatment, Wright began developing a script with co-writer Mark Stay. “Jon and I are both big fans of those 1980s Amblin movies like E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial and The Goonies,” said Stay. “But those films were always set in American suburbia – we wondered why nobody had ever set a film like that in the UK.”

“It came together very quickly, especially for a British film,” Stay continued. “Our elevator pitch was, ‘It’s like The Goonies, but with robots blowing stuff up!’ We took Jon’s treatment to Piers Tempest – one of the producers from Jon’s previous film, Grabbers. The BFI put us under their wing, and before we knew it we had some development money.”

VFX supervisor Paddy Eason was also consulted at this early stage. “I knew Jon because we did the effects for his first two films – Tormented, and an Irish monster movie called Grabbers.” Eason commented. “The first thing I received was the treatment, and the next throw of the dice for me was getting invited to be part of a group that critiqued the script – Jon calls it the ‘Tiny Think Tank’.”

The Tiny Think Tank is an initiative conceived by Wright as a means by which a group of filmmakers can gather together periodically, in order to review scripts in development. “It’s a gang of writers, actors, directors, visual effects people,” Wright explained. “There aren’t any producers or financiers involved – it’s purely creatives. We come together, read a script completely cold, then have a round-table discussion. It was inspired by Pixar. They have their team of creatives – who are also shareholders – who come together and critique each other’s films. The Tiny Think Tank is our low-budget UK version of that, and I think it’s one of the reasons Robot Overlords got made. Our script accelerated in terms of quality much more quickly than it would have done had we been writing it in isolation.”

As part of the Tiny Think Tank, Paddy Eason was able to offer a level of opinion and criticism not commonly afforded people in the visual effects profession. “I had some suggestions from my own visual effects point of view,” Eason remarked. “But I also put some story ideas out to Jon and Mark. As a visual effects person, that’s not normally part of your remit. In fact, on many shows, to put forward story ideas would be viewed as a breach of etiquette. So it was delightful to be invited to give that kind of feedback.”

Nvizible’s association with Robot Overlords developed further when the company became a production partner on the project. Nevertheless, they were still required to bid for the work. “Robot Overlords was a regular production with a bond company and other financiers, so it had to be seen not only that our bid was value for money, but also that our costs weren’t unrealistically low,” Eason pointed out. “Also that, if the unthinkable happened and we dropped the ball, there would be somewhere else to go to get the work done. Obviously it didn’t come to that!”

Key to the success of Robot Overlords was the convincing creation of the alien machines that have descended from outer space to occupy planet Earth. Design concepts for the mechanical marauders developed naturally alongside the story.

“The Robot Empire is stretched across the galaxy,” explained Stay. “If you compare it to the Roman Empire, the Earth is like Caledonia – it’s the last place any of them want to be. Resources are stretched thin. So the Sentries, for example, are quite sorry figures. They walk with a kind of stoop, and they’ve got chips and dents and dinks in their armour, because they’ve been here for three years and survived a war.”

According to the storyline, the Robot Empire studies the inhabitants of each planet they plan to subjugate, and designs an automated invasion force specifically to tap into the psychological profiles of that planet’s inhabitants. This bespoke engineering approach is evident in the design of the Sentries: two-storey, bipedal robots with small heads and enormous, hulking arms.

According to co-writer Mark Stay, the robot Sentries are designed to tap into our instinctive fear of “people with tiny brains and big muscles”.

“In studying us, the robots have discovered that we’re frightened of people with tiny brains and big muscles,” explained Stay. “That informed the design of the Sentry. Our other robots – like the Snipers and Air Drones – are very functional, each with a specific purpose. ”

A different psychological insight led to the design of the Mediator – a kind of robot diplomat that acts as an interface between human beings and their automated oppressors. “The Mediator is made to resemble a child, because they’ve observed that, on the whole, adults don’t behave aggressively towards children,” Jon Wright remarked. “But it’s been designed by an alien species who aren’t familiar with the minutiae of how we react, how our culture is organised. So they’ve got it a bit wrong. They’ve attempted to make something likeable, but they’ve actually made something that’s extremely creepy.”

Early conceptual designs for the robots were developed by storyboard and concept artist, Gabriel Schucan. “Jon and I sat with Gabriel,” Stay recalled. “We scribbled ideas, and he would develop them and send drawings back to me and Jon. That was still very early on in the writing of the script.”

Also at this early stage, the team created the “Robot Compendium”, a manual containing a piece of key art for each robot, drawn by Jack Dudman, along with a description of the machine’s capabilities. “The Robot Compendium, helped us to sell in the script to investors,” remarked Stay. “So it was a really important document for us.”

During the story development process, visual effects constraints influenced what might be achievable, both practically and financially. “While we were still talking about the script, we started doing visual effects breakdowns in a very loose, back-of-an-envelope way,” said Eason. “Some scenes would turn out to be looking very expensive, and that was fed back into the writing process. For example, there was a scene in the woods with our heroes being chased by robots called Octobots. That was quite heavy-duty in terms of visual effects, and wasn’t particularly important in the story. So it was elbowed fairly early on.”

The Overlords Become Real

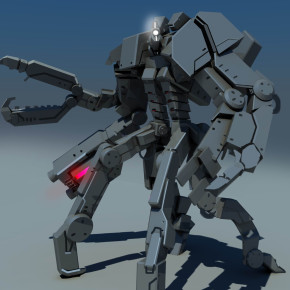

Once Robot Overlords was greenlit, the initial robot concepts were handed over to designer and illustrator Paul Catling, known for his work on films including Guardians of the Galaxy, Captain America: The First Avenger and the Harry Potter series.

“Paul is incredibly productive,” Eason remarked. “He did lots and lots of pen-and-ink designs, just exploring how the robots might look. Early on, some of them were much more organic-looking, and skeletal, and frightening in a slightly Satanic kind of way. Ultimately, we decided the robots should be slightly crude-looking. We wanted to avoid comparisons with Transformers – Jon wanted our robots to look much more industrial. We also wanted them to be slightly reminiscent of WWII Nazi technology.

Although the design of the Sentry was inspired directly by Wright’s inspirational dream, it nevertheless went through a lengthy development process. “One of the original tests we did for the Sentry was a lot more like Robby the Robot,” Wright revealed. “Then he developed into more of an Iron Giant character – we just pushed that design to make it slightly more peculiar. He’s slightly lop-sided, and made up of different geometric shapes. That was partly driven by the plot device of having them fold up into cubes, which was our way of showing that they’ve been deactivated.”

The Mediator robot was played by Craig Garner, whose appearance was enhanced in post-production to give the actor’s skin an unsettling plastic sheen. For some scenes, frames were removed to create staccato movements.

The Mediator, in contrast, was conceived from the beginning as a machine that looked like a human – but not too much like a human. “Right from the beginning, we wanted deliberately to put the Mediator in the uncanny valley, rather than try to avoid it,” Wright noted. “We gave the actor, Craig Garner, perfect false teeth, trimmed his hairline to a perfectly straight line, gelled his hair rock-solid, and tried to remove all of his imperfections and blemishes with make-up. Then that was enhanced in post-production with clean-up, skin glows, making his eyes uniform. Sometimes we’d take out every other frame to give him a kind of clockwork, staccato movement.”

“The bulk of the Mediator work was done in the grade by the colourist, Gareth Spensley, on his Baselight,” Eason elaborated. “However, the software we use at Nvizible for skin work is a suite of NUKE tools that we use as part of our ‘Nhance’ service. These allow us to selectively filter out features of a certain size – for example, wrinkles or spots – while retaining everything else, like image grain, shadows and regular skin texture.”

Robots at Nvizible

With the exception of the Mediator, Nvizible further developed the robot designs in their CG workspace. This process was facilitated by initial 3D work done by Paul Catling. “As Paul progresses his designs, he starts working in 3D,” explained Eason. “He’ll do a render, then go on top of it in Photoshop and paint lighting effects and so on to turn it into an illustration. But the underlying geometry is there. He even rigs it a little so he can move the arms and legs around to come up with certain key poses. So he ended up with some pretty well-realised CG models, which he then gave to us. We had to rebuild them, but they gave us a head-start.”

Nvizible’s robot models were built, rigged and animated primarily using Maya, with additional sculpting work done using ZBrush. “The Sentry ended up being a very complicated rig, with hundreds of moving parts,” Eason noted. “But it does play the biggest part in the film.”

Texturing was applied in MARI, using photographic reference chosen to support the story point that the robots have been operating in a hostile environment for many years, and are therefore both weathered and battle-worn. “There was no decoration on the robots – no painted symbols or information; it was all slabby, raw, metal, moving parts,” Eason noted. “We took photographs of similar unadorned, mechanical things, like old steam engines, big industrial lifts, big heavy things made out of cast iron. Part of the fun was making them nice and weathered – chipped and broken – which also helped to give them scale.”

Many key scenes featuring the robots were shot using a real-time camera-tracking system provided by Nvizible’s sister company, Ncam. The Ncam system allows a camera operator to view pre-visualised CG assets through the viewfinder, adjusted to conform to the parameters of the lens and superimposed in the correct position over the live-action.

“Ncam works without any tracking markers. It lets you see a previs version of your visual effects assets through the camera, or at video village,” Eason explained. “Ncam combines the live video feed from the camera with a render from a workstation, all in real-time, showing your VFX asset in situ. It could be anything from a set extension to a creature.”

Ncam was used during the film’s opening sequence, in which a crazed man runs down a suburban street shouting defiance at his robot oppressors. An Air Drone flies down, warning the man to return to his home; when the man ignores the robot, it vaporises him.

“My view with visual effects is to say, ‘Go ahead and do everything practically that you can, and we’ll deal with it in post.’ Rain? No problem!” – Paddy Eason, Nvizible.

The sequence was shot on location in Bangor, on the outskirts of Belfast, Northern Ireland, using primarily hand-held cameras. Following Wright and Schucan’s storyboards, Nvizible created previs for the sequence, using survey data of the location gathered by members of their Belfast office.

During the night shoot, interactive lighting was coordinated by Fraser Taggart, director of photography, to simulate the glow from the Air Drone’s blue hover-jets, while practical rain simulated a torrential downpour. “Rain gives you a huge amount of visual texture, so it’s a lovely thing to have,” observed Eason. “Generally speaking, my view with visual effects is to say, ‘Go ahead and do everything practically that you can, and we’ll deal with it in post.’ Hand-held cameras? No problem! Rain? No problem! We’ll add CG rain, and we’ll make sure it’s composited behind your rain. But there were a couple of shots where the camera was looking up into the sky, where it would have been too much of a nightmare to have rain falling into the lens, so I did ask them to shoot dry versions to give us the option.”

Practical pyrotechnics were used for the moment when the man is blown up by the robot, somewhat in the manner of a human firework. “We shot the plate with the actor, a clean plate with no actor, and a third plate with the pyro going off,” Eason revealed. “We used a similar camera move each time, but there was no motion control – which is fine as long as everyone’s on the same page. The practical pyro gave us real interactive lighting, and a good clue of how the rain is lit up. We enhanced it with additionally-shot bluescreen pyro elements afterwards.”

For the shots featuring the Air Drone, Ncam was used extensively to aid the shooting of the live-action plates. “It was exciting to see the reaction of the camera operator,” Eason recalled. “Like a lot of people, he was a bit sceptical about Ncam – sometimes people view it as a bit of an encumbrance. But when he realised he was actually able to see the hovering Drone through his viewfinder, and walk around it and choose angles, he was really excited and impressed.”

In one close-up shot, the camera executes a 180° move around the muzzle of the Air Drone’s gun, with the camera racking focus on the barrel. “I don’t think you’d have shot that plate without Ncam,” Eason asserted.

In one close-up shot, the camera executes a 180° move around the muzzle of the Air Drone’s gun, with the camera racking focus on the barrel. “I don’t think you’d have shot that plate without Ncam,” Eason asserted.

While the live-action plates were used for most scenes featuring the flying robot, Nvizible created some backgrounds using 360° HDRI panoramas shot on location by VFX assistant Erran Lake, using a DSLR camera. “Sometimes the plate done with the movie camera might be nice, but technically very difficult,” Eason explained. “So we would create our own version of that using my stitched stills, and put the rain in ourselves.”

Ncam was used for a scene in which a giant robot Sentry pursues Connor (Milo Parker) down a suburban street.

As director, Jon Wright appreciated the freedom afforded by Ncam, notably during a sequence in which a gigantic Sentry chases a boy down a suburban street. “You’re able to shoot something as if it was actually there, so it unlocks your shooting style,” he commented. “We were able to imbue those shots with a hand-held quality, and be quite cavalier about the way we shot. Normally when you shoot a visual effect like that, and there’s nothing there, you’re worried about not framing it up properly.”

“It was quite difficult to set up, positioning the robot and getting good tracks on the camera,” Wright continued, “but it meant we were able to do a running hand-held shot backwards with the boy, framing up the robot above him. The Sentries are massive, so they tend to go out of frame. If there’s nothing there, it makes the operator nervous and they tend to err on the side of caution and give you a slightly peculiar, lop-sided frame. If they can see the thing, they frame it much more naturally, and you get a much more interesting shot.”

“I imagine in years to come this will be fairly standard practice,” Wright concluded. “The days of tennis balls on sticks are numbered.”

Watch a video of the live NCam feed as seen by the camera operator:

By the time post-production began, Robot Overlords already existed in rough-cut form, since editor Matt Platts-Mills had been present on location throughout production, cutting each day’s rushes together into a rough assembly. “It was very helpful to have Matt with us, cutting as we went,” Eason observed. “By the time the shoot was done, we were in a good position to hit the ground running on certain key visual effects scenes.”

Since much of the film had been shot hand-held using anamorphic lenses, one of the first challenges for the visual effects team was tracking. Peanut FX handled all the film’s tracking requirements, delivering 3D layouts for roughly 115 shots, mostly with 3D camera and/or object tracks for set extensions and robot integration.

“We mainly used 3DEqualizer,” commented Amelie Guyot, matchmove supervisor at Peanut. “We find it great for solving anamorphic camera tracks when lens distortion grids and camera info are available. We were provided with a lidar scan model for scenes involving a castle, which we used to perfectly match the plates – 3D scans are always very helpful, especially with anamorphic shots. We also used Autodesk’s Matchmover to calibrate sets; it’s still one of our favourite tools for image-based 3D reconstruction.”

“Tracking was a concern early on,” Eason admitted, “but the guys at Peanut absolutely rocked it and did a brilliant job.”

Tracking for “Robot Overlords” was handled by Peanut FX, who worked meticulously to deal with director Wright’s extensive use of hand-held cameras, and some challenging sequences in which the robots interact directly with humans and their technology.

During post-production, Jon Wright made himself available to the Nvizible team on a regular basis. “I made a point of remaining on the film throughout the time that Nvizible were working on the visual effects, so I could go in and out of their offices at my leisure,” the director stated. “It saves a lot of work if you’re seeing updated shots regularly – you tend to have less waste. I don’t know how to run Nuke or anything, but I think I’m quite geeky, and have a good understanding of how effects work. I can tell if something’s going to be quick to do, or time-consuming. I think maybe some directors don’t have that.”

With regard to the animation of the robots, Wright paid particular attention to the way the movement of the metal invaders expressed their character – or rather, their lack of it. “There’s a tendency to anthropomorphise robots,” Wright observed. “Our robots are quite implacable, so it was important to strip out emotion.”

Even given this direction, nevertheless Wright found that individual animators inevitably had their own take on how the robots should move. “After a bit I could guess quite accurately who’d animated what, because they bring their own personality to it,” he commented. “It got to a point where I would say, ‘I know this shot would be great for this animator,’ on the basis of what they’d done before.”

Lighting the CG robots brought its own set of challenges, due to the difficulty of making metallic objects look both highly reflective and convincingly three-dimensional. “It’s a bit of a double-edged sword,” Eason remarked. “If you’ve got good HDRIs for everything, you get good reflections, but because most of what you see with metal is based on reflections, it’s hard to make stuff that’s physically juicy, with a nice keylight and a nice fill light. You’re always fighting that chrome robot thing, where it all looks a bit floaty and unlit.”

Riding the Skyship

One of the most difficult visual effects sequences occurs at the film’s climax, when Sean finds himself riding through the skies on the front of the enormous robot Skyship.

“They were really hard shots, because they were extremely ambitious,” Wright admitted. “I’d imagine that even the likes of ILM working for J.J. Abrams would have found those shots tough to get right.”

Once again, NCam was used to combine a previs version of the Skyship with the live-action as it was being shot on a small studio set. “The set had a slight bounce, which made things interesting,” Eason recalled. “We ended up replacing all the practical set with CG, although it was useful to have it there for reference, shadow catching and so on.”

The film’s ambitious climactic scenes, during which Sean (Callan McAuliffe) rides on the exterior of the massive Skyship, proved particularly challenging.

In post-production, the low-resolution Skyship model was replaced by its high-resolution counterpart. “The main challenges with the Skyship came in look-dev, working out how to make a big shiny collection of metal blocks look big and scary and cool,” Eason commented. “In reality, large steel things tend to look like concrete, so we had to cheat the physics of the renders quite a bit. We had a lot of fun with the Skyship engines – big jets of dirty orange and blue fire. Our FX lead, Wayde Duncan Smith, did a great job of simulating all that stuff in Houdini.”

Because the sequence featured multiple camera angles, with moves that were very specific to the animation of the various characters and craft, it was deemed unfeasible to shoot live-action background plates. Instead, generic aerial plates of landscapes were shot using an array of DSLR cameras.

“We flew the route in a chopper several times, shooting 160° panoramas using three Canon 5Ds, shooting stills at 3fps,” Eason revealed. “We fed these image sequences through a pipeline of undistortion, stitching, stabilising, optical flow and re-projection, to make beautiful background plates of moving land for all the flying Skyship shots. It was hard work, but our Nuke artist, Antoine Jannic, absolutely nailed it.”

Watch a video of a completed shot from the Skyship sequence:

Enter the Spitfire

Also featured during the film’s finale is that most British of icons – a Supermarine Spitfire. The old-school technology of the WWII fighter plane proves pivotal in the battle against the robots, whose jamming devices have grounded more sophisticated jet aircraft.

The production shot live-action of the historic plane on the ground using a mock-up provided by Gateguards UK. An authentic Spitfire was also made available for one day of the shoot by The Aircraft Restoration Company, Duxford. In addition, Nvizible built a CG Spitfire which they used for additional aerial shots.

Jon Wright (right) directs the action around the museum-piece Supermarine Spitfire, on location in the Isle of Man.

“We used the mock-up Spitfire in a remote, disused quarry location on the Isle of Man,” explained Eason. “Then we also had the real Spitfire fly out to us for the day. We positioned it on the airfield and dressed it similar to how the mock-up had been in the quarry. It was a huge privilege to have a real museum-piece there, and a dream for us in terms of creating our CG Spitfire for the flying shots, because we were able to get perfect reference, taking thousands of photographs, right down to every rivet.”

Eason was doubly delighted when he found himself booked in for a flight in a two-seat Spitfire. “The producer, Piers Tempest, knew I was a big fan of Spitfires, and he made a casual comment: ‘We’ll get you a flight in it.’ I didn’t believe it would ever happen, but a couple of months later it was arranged for me to go to the Imperial War Museum at Duxford. I got to fly around, and control the Spitfire, and everything. Ostensibly it was to record audio inside the plane – I was wired for sound – but also it was just a marvellous day out.”

Looking back at his experience of working on Robot Overlords, Mark Stay noted the benefits brought by the collaborative process: “I’ve been involved in the whole procedure in a way that many other writers aren’t usually. I was writing the novelisation at the same time, so I would email Paddy to ask questions like, ‘What colour are the engines?’ He would invite me over to Nvizible so I could sit in on VFX test screenings, and I would be there furiously scribbling all this stuff down for the novel. I’ve been really blessed with the access that I’ve had.”

“It was a delightful experience, because of our creative involvement from beginning to end,” Paddy Eason added. “I love the fact that it’s quite an unusual British film – very charming and quirky, starting at a very small personal scale and ending up quite epic and extraordinary.”

The film’s ambition is something that Jon Wright is proud of. However, he remains sanguine about the challenges involved in bringing such a film to the screen.

“It’s a bit of a shame that we aren’t really making these kinds of movies in Britain and Ireland, and that British cinemagoers almost prefer to go and see American films over British films. And we’ve got all our best filmmakers going across the water to do remakes,” Wright commented. “But the truth is, when you make a movie like this, you go up against massive Hollywood blockbusters, and it’s difficult to deliver in the way that they deliver. So we tried to focus on character, and give the film a different tone to a typical Hollywood movie at the moment – not dark and moody, but kind of light-hearted and optimistic. Our kids swear a lot and are playful, rather than being the earnest, soul-searching types you get in typical American YA movies.”

Echoing Wright’s thoughts, Eason recalled, “I remember one meeting we had early on, where we pitched the project to quite a well-known film producer. This producer said, ‘If you pull it off, I’ll eat my hat.’ So now we’re going to get a nice hat-shaped cake made for him!”

Having enjoyed limited theatrical release across the UK through Signature, Robot Overlords may also be gaining momentum as a TV series. “We have strong interest from two big broadcasters, in the US and the UK,” Wright revealed. “In 2015, television is probably the way to go with this sort of project. We could really explore into the human politics of the situation – life under enemy occupation. Obviously, the occupation is going on across the entire planet, so there’s a million different directions you could expand the story into. And ten hours of television is probably more exciting than another 90-minute film. It could be very good – watch this space.”

Robot Overlords is now available on DVD.

- Robot Overlords on Facebook

- Nvizible

- Peanut FX

- Boundary VFX

- Jon Wright at IMDb

- Paddy Eason at IMDb

- Mark Stay – Unusually Tall Stories

- Amelie Guyot at IMDb

- The Foundry – NUKE, MARI

- Autodesk – Maya, Mudbox, Matchmover

- Pixologic – ZBrush

- Side Effects – Houdini

Special thanks to Marek Steven, Alex Coxon, Piers Tempest and Phil Guest. “Robot Overlords” photographs and video copyright © 2015 and courtesy of Tempo Productions and Nvizible.

If you liked this article, you may also be interested in:

- The robots in Ex Machina: VFX Q&A with Andrew Whitehurst

- True AI, or clever simulation? Transcendence movie has Johnny Depp crossing the Singularity

- 12 favorite robot movies – new and old

- The real soft robots that inspired Baymax, with Chris Atkeson

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: c-Arts-Entertainment, entertainment, film, robohub focus on arts and entertainment, sci-fi