Robohub.org

Emergent behavior by minimizing chaos

By Glen Berseth

All living organisms carve out environmental niches within which they can maintain relative predictability amidst the ever-increasing entropy around them (1), (2). Humans, for example, go to great lengths to shield themselves from surprise — we band together in millions to build cities with homes, supplying water, food, gas, and electricity to control the deterioration of our bodies and living spaces amidst heat and cold, wind and storm. The need to discover and maintain such surprise-free equilibria has driven great resourcefulness and skill in organisms across very diverse natural habitats. Motivated by this, we ask: could the motive of preserving order amidst chaos guide the automatic acquisition of useful behaviors in artificial agents?

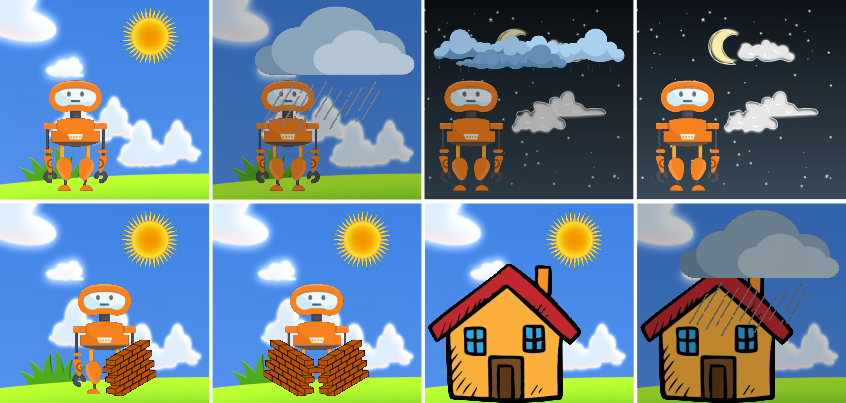

How might an agent in an environment acquire complex behaviors and skills with no external supervision? This central problem in artificial intelligence has evoked several candidate solutions, largely focusing on novelty-seeking behaviors (3), (4), (5). In simulated worlds, such as video games, novelty-seeking intrinsic motivation can lead to interesting and meaningful behavior. However, these environments may be fundamentally lacking compared to the real world. In the real world, natural forces and other agents offer bountiful novelty. Instead, the challenge in natural environments is allostasis: discovering behaviors that enable agents to maintain an equilibrium (homeostasis), for example to preserve their bodies, their homes, and avoid predators and hunger. In the example below we shown an example where an agent is experiencing random events due to the changing weather. If the agent learns to build a shelter, in this case a house, the agent will reduce the observed effects from weather.

We formalize homeostasis as an objective for reinforcement learning based on surprise minimization (SMiRL). In entropic and dynamic environments with undesirable forms of novelty, minimizing surprise (i.e., minimizing novelty) causes agents to naturally seek an equilibrium that can be stably maintained.

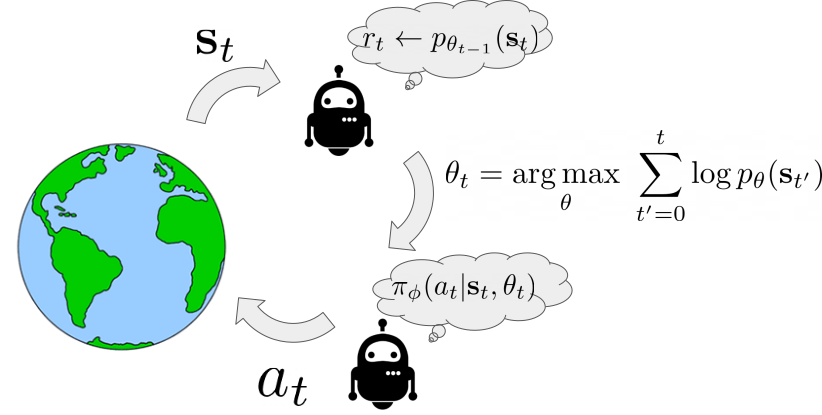

Here we show an illustration of the agent interaction loop using SMiRL. When the agent observes a state $\mathbf{s}$, it computes the probability of this new state given the belief the agent has $r_{t} \leftarrow p_{\theta_{t-1}}(\textbf{s})$. This belief models the states the agent is most familiar with – i.e., the distribution of states it has seen in the past. Experiencing states that are more familiar will result in higher reward. After the agent experience a new state it updates its belief $p_{\theta_{t-1}}(\textbf{s})$ over states to include the most recent experience. Then, the goal of the action policy $\pi(a|\textbf{s}, \theta_{t})$ is to choose actions that will result in the agent consistently experiencing familiar states. Crucially, the agent understands that its beliefs will change in the future. This means that it has two mechanisms by which to maximize this reward: taking actions to visit familiar states, and taking actions to visit states that will change its beliefs such that future states are more familiar. It is this latter mechanism that results in complex emergent behavior. Below, we visualize a policy trained to play the game of Tetris. On the left the blocks the agent chooses are shown and on the right is a visualization of $p_{\theta_{t}}(\textbf{s})$. We can see how as the episode progresses the belief over possible locations to place blocks tends to favor only the bottom row. This encourages the agent to eliminate blocks to prevent board from filling up.

Left: Tetris. Right: HauntedHouse.

Emergent behavior

The SMiRL agent demonstrates meaningful emergent behaviors in a number of different environments. In the Tetris environment, the agent is able to learn proactive behaviors to eliminate rows and properly play the game. The agent also learns emergent game playing behavior in the VizDoom environment, acquiring an effective policy for dodging the fireballs thrown by the enemies. In both of these environments, stochastic and chaotic events force the SMiRL agent to take a coordinated course of action to avoid unusual states, such as full Tetris boards or fireball explorations.

Left: Doom Hold The Line. Right: Doom Defend The Line.

Biped

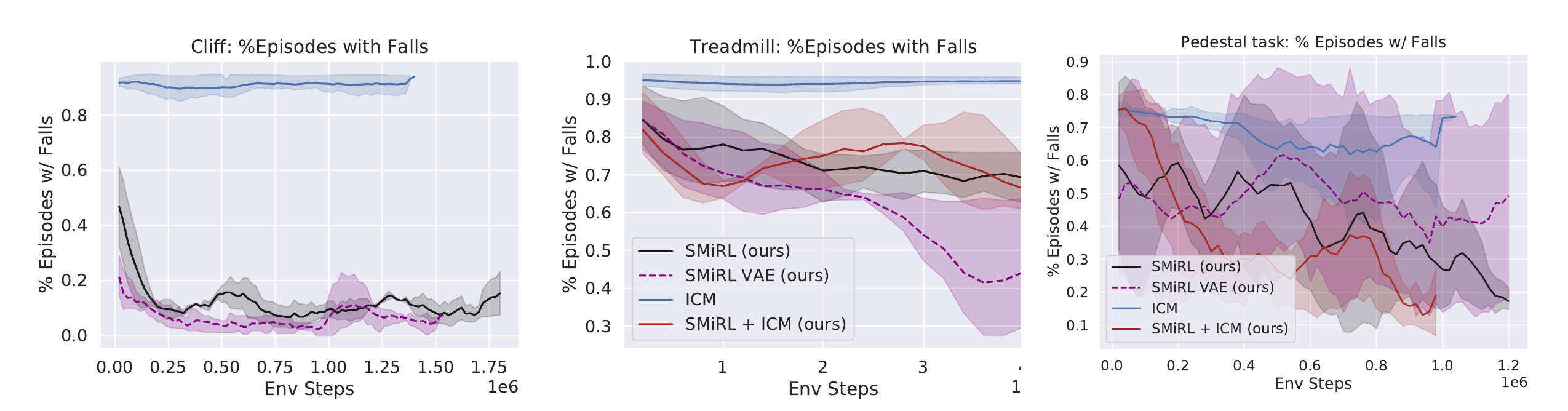

In the Cliff environment, the agent learns a policy that greatly reduces the probability of falling off of the cliff by bracing against the ground and stabilize itself at the edge, as shown in the figure below. In the Treadmill environment, SMiRL learns a more complex locomotion behavior, jumping forward to increase the time it stays on the treadmill, as shown in figure below.

Left: Cliff. Right: Treadmill.

Comparison to Intrinsic motivation:

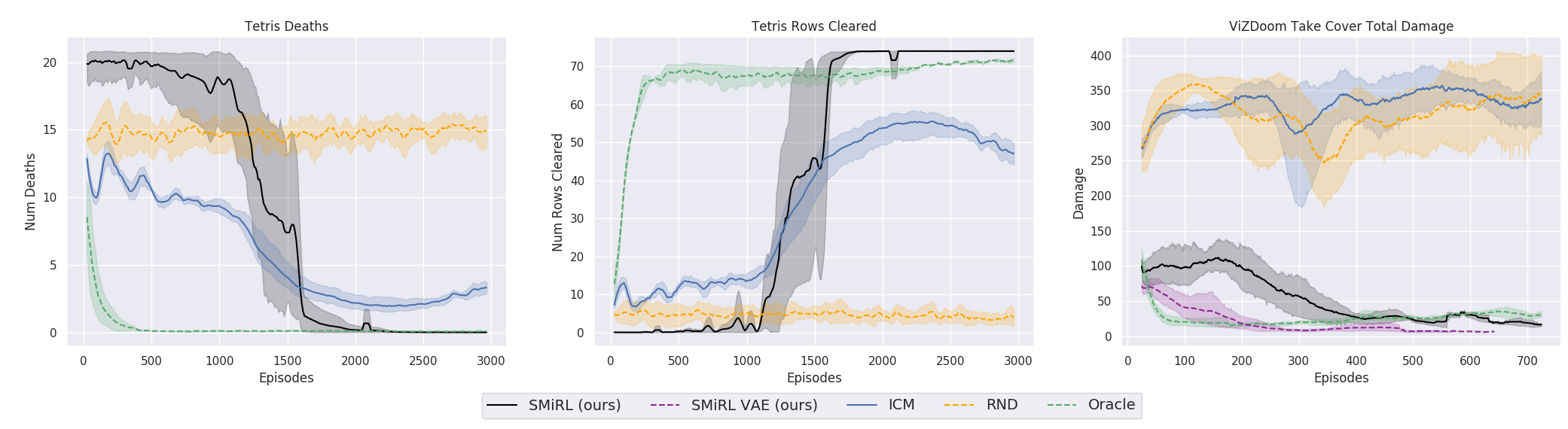

Intrinsic motivation is the idea that behavior is driven by internal reward signals that are task independent. Below, we show plots of the environment-specific rewards over time on Tetris, VizDoomTakeCover, and the humanoid domains. In order to compare SMiRL to more standard intrinsic motivation methods, which seek out states that maximize surprise or novelty, we also evaluated ICM (5) and RND (6). We include an oracle agent that directly optimizes the task reward. On Tetris, after training for $2000$ epochs, SMiRL achieves near perfect play, on par with the oracle reward optimizing agent, with no deaths. ICM seeks novelty by creating more and more distinct patterns of blocks rather than clearing them, leading to deteriorating game scores over time. On VizDoomTakeCover, SmiRL effectively learns to dodge fireballs thrown by the adversaries.

The baseline comparisons for the Cliff and Treadmill environments have a similar outcome. The novelty seeking behavior of ICM causes it to learn a type of irregular behavior that causes the agent to jump off the Cliff and roll around on the Treadmill, maximizing the variety (and quantity) of falls.

SMiRL + Curiosity:

While on the surface, SMiRL minimizes surprise and curiosity approaches like ICM maximize novelty, they are in fact not mutually incompatible. In particular, while ICM maximizes novelty with respect to a learned transition model, SMiRL minimizes surprise with respect to a learned state distribution. We can combine ICM and SMiRL to achieve even better results on the Treadmill environment.

Left: Treadmill+ICM. Right: Pedestal.

Insights:

The key insight utilized by our method is that, in contrast to simple simulated domains, realistic environments exhibit dynamic phenomena that gradually increase entropy over time. An agent that resists this growth in entropy must take active and coordinated actions, thus learning increasingly complex behaviors. This is different from commonly proposed intrinsic exploration methods based on novelty, which instead seek to visit novel states and increase entropy. SMiRL holds promise for a new kind of unsupervised RL method that produces behaviors that are closely tied to the prevailing disruptive forces, adversaries, and other sources of entropy in the environment.

This article was initially published on the BAIR blog, and appears here with the author’s permission.

tags: herotagrc