Robohub.org

Schiaparelli, are you there? The high risks of space robotics again crash home

In Darmstadt, Germany, European Space Agency (ESA) teams are scrambling to confirm contact with the Entry, Descent and Landing Demonstrator Module (EDM), Schiaparelli—the spectre of Philae still haunting the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC). Whether or not ESA ever speak to Schiaparelli again, the risky business of space robotics is once more laid bare.

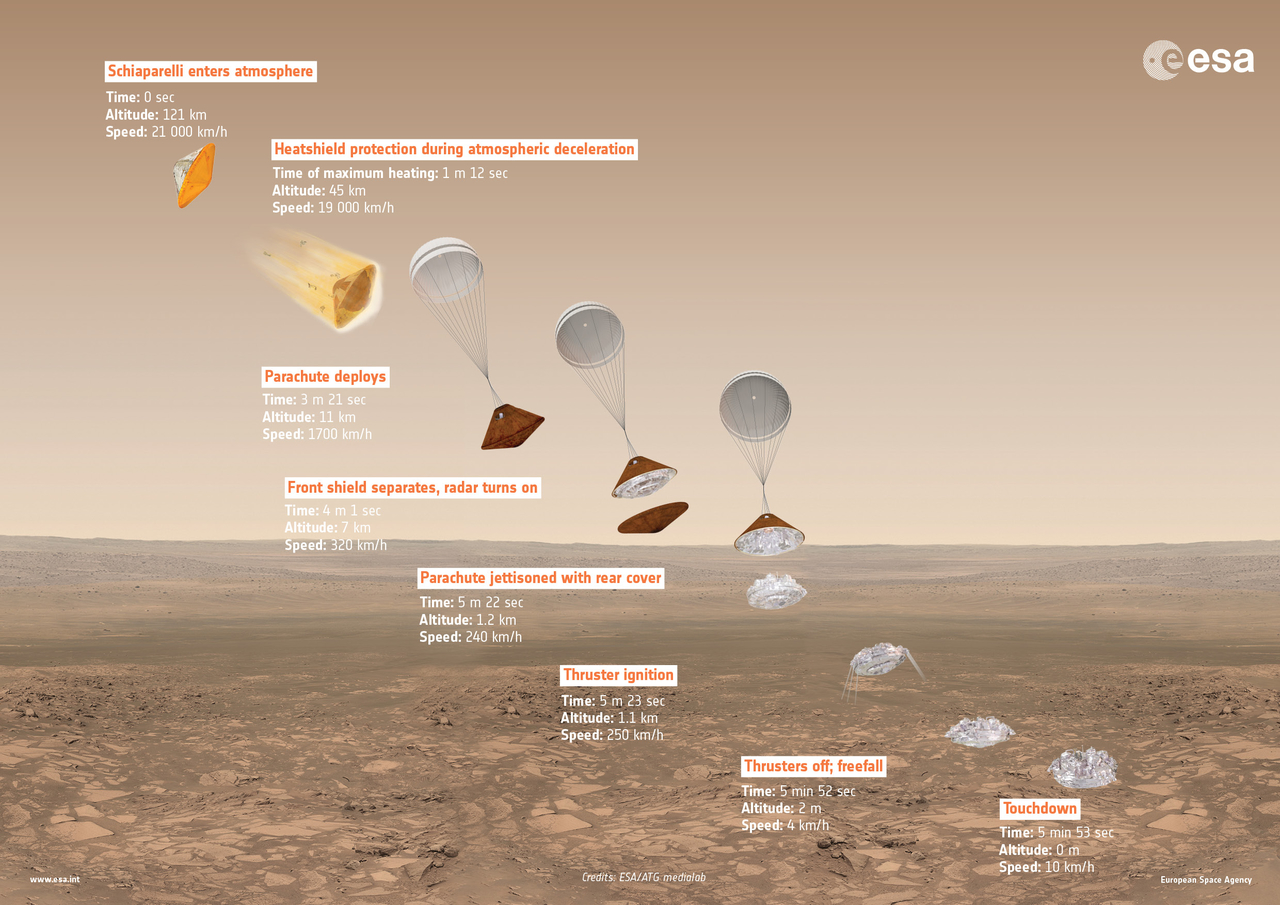

After Schiaparelli’s release from its mothership—The Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO)—the 577 kg EDM was programmed to autonomously perform an automated landing sequence, with parachute deployment and front heat shield release between 11 and 7 km above the Martian surface, all the time collecting data on the pressure, surface temperature and heat flux on its back cover as it passed through the atmosphere. Then, 1100 m from the ground, retrorocket braking was supposed to slow the EDM before a final fall from a height of 2 m, protected by a crushable structure. But sometime during this process the signal was lost. ESA_Shiaparelli’s twitter feed soon fell silent also.

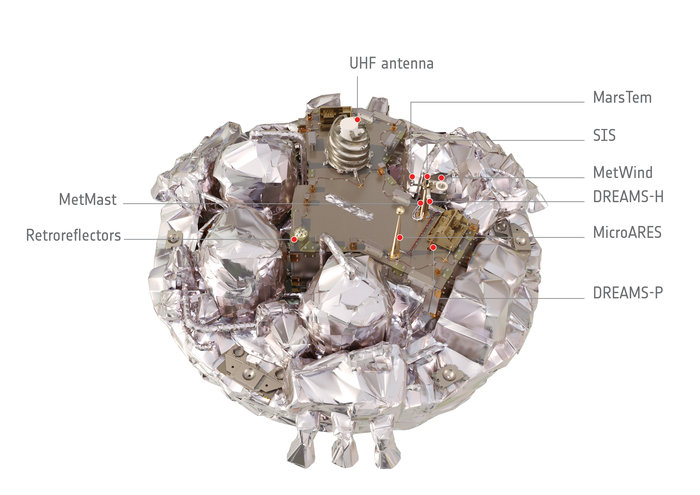

If Schiaparelli reached the surface safely, its batteries should be able to support operations for three to ten days, offering multiple opportunities to re-establish a communication link and collect data from its suite of sensors designed to measure wind speed and direction, humidity, pressure, atmospheric temperature, transparency of the atmosphere, and atmospheric electrification. But if contact is never restored, it’ll be a hefty blow to ExoMars and ESA’s aim of testing key technologies in preparation for their contribution to subsequent missions to Mars, including a planned 2020 rover that will carry a drill and a suite of instruments dedicated to exobiology and geochemistry research.

Such robotic technology has the potential to stretch our cosmological horizon, and perhaps even detect traces of extra-terrestrial life. But there’s a cost. The ExoMars program runs up a bill totaling €1.3 billion, and such failures (if a failure it be) naturally raise questions of risk versus reward, particularly in tight economic times. Michael Johnson of the Pervasive Media Studio, Bristol, and founder of PocketSpacecraft.com, once told me during an interview: “About 50% of space missions fail after launch.” He shrugged. “That’s life… This is a high risk, high reward activity.”

In no other field of robotics is the potential of catastrophic failure so present and accepted. But how long can this attitude be maintained? The consensual public funding of—and indeed existence of—future space missions is parasitic upon the success of space robots and automated technology, and vice versa. Can you hear us Schiaparelli?

…

Come in, Schiaparelli.

…?

BUT ALL IS NOT LOST. The difficulties surrounding the mission’s EDM might potentially overshadow the successes of its TGO, which successfully performed the long 139-minute burn required to be captured by Mars, and has entered an elliptical orbit around the Red Planet. TGO’s Mars orbit Insertion burn lasted from 13:05 to 15:24 GMT on 19 October, reducing the spacecraft’s speed and direction by more than 1.5 km/s. The TGO is now on its planned orbit around Mars, primed with a suit of scientific equipment to measure the Martian atmosphere from on high. You win some, you lose some. This 50:50 success rate exemplifies the apparent nature of space robotics.

Click here to keep up to date with the latest ExoMars developments.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also be interested in:

- Drone learns to see in zero-gravity

- Robots Podcast #217: LunaRoo, with Jürgen Leitner

- The four coolest NASA robots

- Exoskeletons: From helping people walk to controlling robots in space

- NASA Space Robotics Challenge prepares robots for the journey to Mars

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: Automation, ESA, Mars, Philae, robot, rover, Space