Robohub.org

Space for the masses as helium balloons and remote control planes reach through the stratosphere

Helium balloons are being used to carry people, experiments and satellite launchers into near space. Image courtesy of Zero2Infinity

Space will soon be within the grasp of everyday people, small countries, researchers or start-up companies thanks to a fleet of low-cost launch vehicles under development across Europe.

From remote control drones that can fire rockets into orbit from the edge of space, to giant helium balloons that could carry tourists, science experiments or satellite launchers into the stratosphere, small-scale start-ups are stepping into the control room and embarking on a new low-cost space race.

It represents an exciting new wave of space travel, following in the vapour trails of private companies such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX or Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic.

The IssueThe EU is aiming to encourage private companies to develop low-cost launch systems as part of its Space Strategy for Europe announced in October this year.

The objective of EU funding for research into space technologies is to enable Europe to access space independently and affordably, and strengthen the capability of European scientists and engineers.

Between 2014 and 2020, it plans to spend over EUR 12 billion on three space programmes – satellite navigation, earth observation and space research.

Where once only global superpowers with vast budgets could go, Europe’s entrepreneurs and innovators will soon be travelling for a fraction of the cost.

One of these innovators is Zero 2 Infinity, a Spanish start-up working on helium balloon-borne spacecraft.

‘It’s the cheaper way because it’s more efficient, you need fewer engineers to build it,’ explained Jose Mariano Lopez-Urdiales, chief executive.

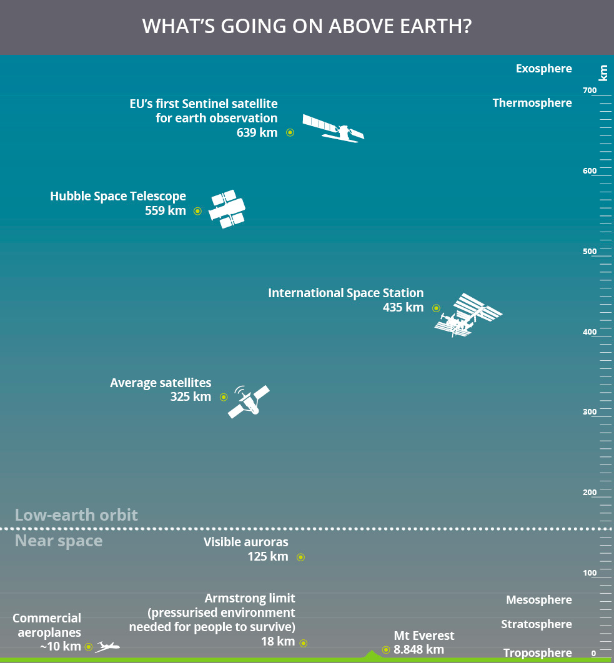

Near space

The idea is that the balloon would carry a passenger pod into what is known as near space, somewhere between 20 km and 100 km above the earth’s surface, or carry its small rocket-powered Bloostar spacecraft which it could then launch much higher into low-earth orbit.

Zero 2 Infinity customers are already balloon launching satellites for short periods of high-altitude testing, and the company has EUR 140 million in expressions of interest for full satellite launches.

It was the leader of the EU-backed HELIUM project, which developed the concept for a near-space European laboratory that allows orbiting research at 36 km, and the life support system for the two pilots in the initial six-hour flights.

Although space tourists could soon be using the balloon launch system to take selfies in near space, the first passengers are likely to be scientists, according to Lopez-Urdiales.

Aiming higher than the balloon satellite launcher’s range of 600 km, Europe’s ALTAIR project is readying the blueprints for a remote-controlled aircraft which would use a rocket launch module to blast sub-200 kilogramme satellite payloads into orbit and take off in 2020 at the earliest.

Runway

ALTAIR’s launch system — similar to Virgin Galactic’s piloted White Knight 2 space tourism aircraft in appearance and general function — would take off from a runway, before ferrying satellites up to an altitude of 12-15 km and igniting its rocket payload.

But the similarities end there. ALTAIR project manager Nicolas Bérend says the project is focused on affordable, remote-controlled launches, calling on the experience of French space centres CNES and Onera, creators of the Eole automated launch aircraft demonstrator which is the project’s precursor.

By the end of the EU-funded program in 2018, the six-country collaboration will have a final concept for the unmanned aircraft, its hybrid propulsion engine rocket launcher and ground operations, and will demonstrate its launch technology by doing suborbital tests using a scale model.

‘If Europe does not take the chance now, then we may lose this possibility.’Bertil Oving, Netherlands Aerospace Centre

By removing the human pilot and designing a facility geared towards a high launch frequency and minimal staffing, they hope to bring down the costs enough to make the project economically viable.

‘It is essential to the project’s success to restrict launch costs to around EUR 4 million, a price the team’s market analysts consider to be a competitive launch price,’ said Bérend.

That should give them access to a growing market for small satellite launches, often in the form of so-called CubeSats, nanosatellites normally no more than 10 centimetres wide, a market where Europe is lagging behind at the moment.

Even though Europe covers large-to-medium launches with its Ariane 6 and Vega rockets, and suborbital rockets from the Andøya launch site in Norway, it has no small-satellite solution.

‘The small satellites are all launched outside of Europe with Russian or Indian launchers,’ said Bertil Oving, of the Netherlands Aerospace Centre. ‘There is a small-satellite market, it’s booming and if Europe does not take the chance now, then we may lose this possibility.’

He is the coordinator of SMILE, an EU-funded project designing a small-scale launcher for satellites of up to 50 kg.

SMILE will design and start component testing of a standard-format rocket, along with the necessary upgrades to the Andøya facility, by 2019, keeping costs below EUR 50 000 per kilogramme launched, and hopefully cutting the expensive wait for satellites to be able to piggyback on one of the larger rockets.

3D printing

Larger rockets benefit from an economy of scale, and SMILE’s competitiveness would come from advances in reusable components, automated composite manufacturing, 3D printing and also high-volume production.

‘The payload versus the total mass becomes smaller when the launcher is smaller, so it’s a cost aspect challenge,’ said Oving.

He said SMILE is pushing advances in reusable liquid-fuelled engines and its automated manufacturing advances would have automotive and aviation industry uses, but he thinks the biggest implications of low-cost, low-orbit access will be for consumers.

‘The idea for small satellites like CubeSats is to approach them like FedEx & DHL,’ he said. ‘We will simply bring it to where you want to have it.’

European organisations may soon make it easier to get equipment into near space and low-earth orbit.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also want to read these Horizon related articles:

- EU’s Horizon 2020 has funded $179 million in robotics PPPs

- Keeping a robotic eye on pollution

- Protecting European wine: Vinbot rover optimises harvest and quality

- A helping hand for high-tech firms

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: Horizon 2020, innovation, Space