Robohub.org

Task Planning in robotics

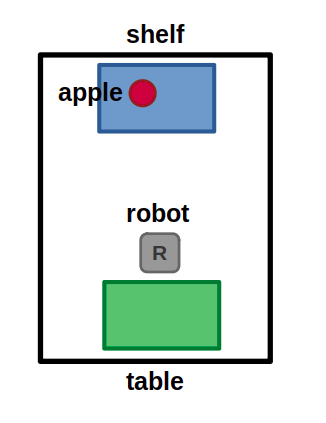

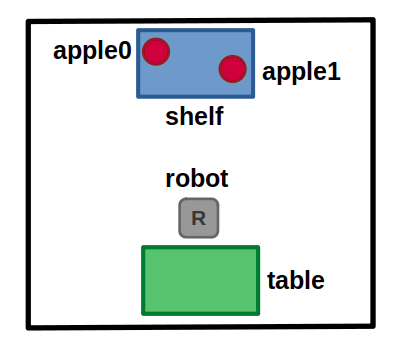

Suppose we have a robot in a simple world like the one below. Let’s consider commanding our robot to perform a task such as “take the apple from the shelf and put it on the table”.

Simple task planning example world: A robot can move between a finite set of locations, and can pick and place objects at those locations.

I would argue we humans have pretty good intuition for how a robot could achieve this task. We could describe what the robot should do by breaking the solution down into individual actions. For example:

- Move to the shelf

- Pick up the apple

- Move back to the table

- Place the apple

This is fine for our simple example — and in fact, is also fine for many real-world robotics applications — but what if the task gets more complicated? Suppose we add more objects and locations to our simple world, and start describing increasingly complex goals like “make sure all the apples are on the table and everything else is in the garbage bin”? Furthermore, what if we want to achieve this in some optimal manner like minimizing time, or number of total actions? Our reasoning quickly hits its limit as the problem grows, and perhaps we want to consider letting a computer do the work.

This is what we often refer to as task planning: Autonomously reasoning about the state of the world using an internal model and coming up a sequence of actions, or a plan, to achieve a goal.

In my opinion, task planning is not as popular as other areas in robotics you might encounter because… quite frankly, we’re just not that good at robotics yet! What I mean is that robots are complicated, and many commercially available systems are automating simple, repetitive tasks that don’t require this level of high-level planning — it would be overkill! There are many lower-level problems to solve in robotics such as standing up good hardware, robust sensing and actuation, motion planning, and keeping costs down. While task planning skews towards more academic settings for this reason, I eagerly await the not-so-distant future where robots are even more capable and the entire industry is thinking more about planning over longer horizons and increasingly sophisticated tasks.

In this post, I will introduce the basic pieces behind task planning for robotics. I will focus on Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL) and take you through some basic examples both conceptually and using the pyrobosim tool.

Defining a planning domain

Task planning requires a model of the world and how an autonomous agent can interact with the world. This is usually described using state and actions. Given a particular state of the world, our robot can take some action to transition to another state.

Over the years, there have been several languages used to define domains for task planning. The first task planning language was the STanford Research Institute Problem Solver (STRIPS) in 1971, made popular by the Shakey project.

Since then, several related languages for planning have come up, but one of the most popular today is Planning Domain Definition Language (PDDL). The first PDDL paper was published in 1998, though there have been several enhancements and variations tacked on over the years. To briefly describe PDDL, it’s hard to beat the original paper.

“PDDL is intended to express the “physics” of a domain, that is, what predicates there are, what actions are possible, what the structure of compound actions is, and what the effects of actions are.”

– GHALLAB ET AL. (1998), PDDL – THE PLANNING DOMAIN DEFINITION LANGUAGE

The point of languages like PDDL is that they can describe an entire space of possible problems where a robot can take the same actions, but in different environments and with different goals. As such, the fundamental pieces of task planning with PDDL are a task-agnostic domain and a task-specific problem.

Using our robot example, we can define:

- Domain: The task-agnostic part

- Predicates: (Robot ?r), (Object ?o), (Location ?loc), (At ?r ?loc), (Holding ?r ?o), etc.

- Actions: move(?r ?loc1 ?loc2), pick(?r ?o ?loc), place(?r ?o ?loc)

- Problem: The task-specific part

- Objects: (Robot robot), (Location shelf), (Location table), (Object apple)

- Initial state: (HandEmpty robot), (At robot table), (At apple shelf)

- Goal specification: (At apple table)

Since domains describe how the world works, predicates and actions have associated parameters, which are denoted by ?, whereas a specific object does not have any special characters to describe it. Some examples to make this concrete:

- (Location ?loc) is a unary predicate, meaning it has one parameter. In our example, shelf and table are specific location instances, so we say that (Location table) and (Location shelf) are part of our initial state and do not change over time.

- (At ?r ?loc) is a binary predicate, meaning it has two parameters. In our example, the robot may begin at the table, so we say that (At robot table) is part of our initial state, though it may be negated as the robot moves to another location.

PDDL is an action language, meaning that the bulk of a domain is defined as actions (sometimes referred to as operators) that interact with our predicates above. Specifically, an action contains:

- Parameters: Allow the same type of action to be executed for different combinations of objects that may exist in our world.

- Preconditions: Predicates which must be true at a given state to allow taking the action from that state.

- Effects: Changes in state that occur as a result of executing the action.

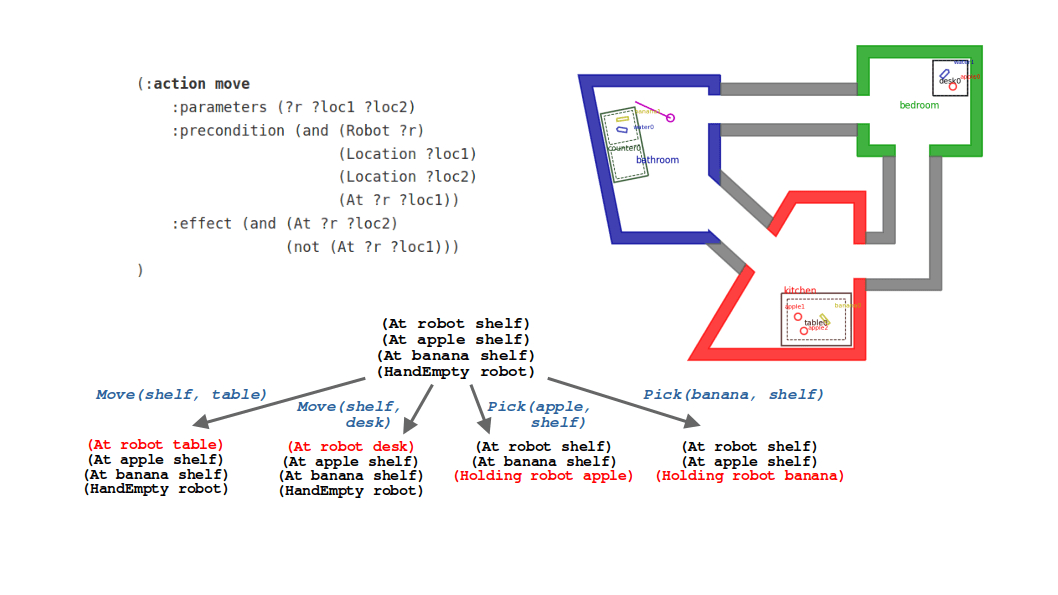

For our robot, we could define a move action as follows:

(:action move

:parameters (?r ?loc1 ?loc2)

:precondition (and (Robot ?r)

(Location ?loc1)

(Location ?loc2)

(At ?r ?loc1))

:effect (and (At ?r ?loc2)

(not (At ?r ?loc1)))

)

In our description of move, we have

- Three parameters ?r ?loc1, and ?loc2.

- Unary predicates in the preconditions that narrow down the domain of parameters that make an action feasible — ?r must be a robot and ?loc1 and ?loc2 must be locations, otherwise the action does not make sense.

- Another precondition that is state-dependent: (At ?r ?loc1). This means that to perform a move action starting at some location ?loc1, the robot must already be in that location.

Note that in some cases, PDDL descriptions allow for typing, which lets you define the domain of actions inline with the parameters rather than explicitly including them as unary predicates — for example, :parameters ?r – Robot ?loc1 – Location ?loc2 – Location … but this is just syntactic sugar.

Similarly, the effects of the action can add new predicates or negate existing ones (in STRIPS these were specified as separate addition and deletion lists). In our example, after performing a move action, the robot is no longer at its previous location ?loc1 and instead is at its intended new location ?loc2.

A similar concept can be applied to other actions, for example pick and place. If you take some time to process the PDDL snippets below, you will hopefully get the gist that our robot can manipulate an object only if it is at the same location as that object, and it is currently not holding something else.

(:action pick

:parameters (?r ?o ?loc)

:precondition (and (Robot ?r)

(Obj ?o)

(Location ?loc)

(HandEmpty ?r)

(At ?r ?loc)

(At ?o ?loc))

:effect (and (Holding ?r ?o)

(not (HandEmpty ?r))

(not (At ?o ?loc)))

)

(:action place

:parameters (?r ?o ?loc)

:precondition (and (Robot ?r)

(Obj ?o)

(Location ?loc)

(At ?r ?loc)

(not (HandEmpty ?r))

(Holding ?r ?o))

:effect (and (HandEmpty ?r)

(At ?o ?loc)

(not (Holding ?r ?o)))

)

So given a PDDL domain, we can now come up a plan, or sequence of actions, to solve various types of problems within that domain … but how is this done in practice?

Task planning is search

There is good reason for all this overhead in defining a planning domain and a good language to express it in: At the end of the day, task planning is solved using search algorithms, and much of the literature is about solving complex problems as efficiently as possible. As task planning problems scale up, computational costs increase at an alarming rate — you will often see PSPACE-Complete and NP-Complete thrown around in the literature, which should make planning people run for the hills.

State-space search

One way to implement task planning is using our model to perform state-space search. Given our problem statement, this could either be:

- Forward search: Start with the initial state and expand a graph until a goal state is reached.

- Backward search: Start with the goal state(s) and work backwards until the initial state is reached.

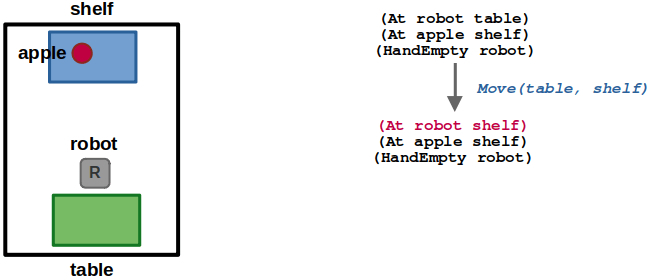

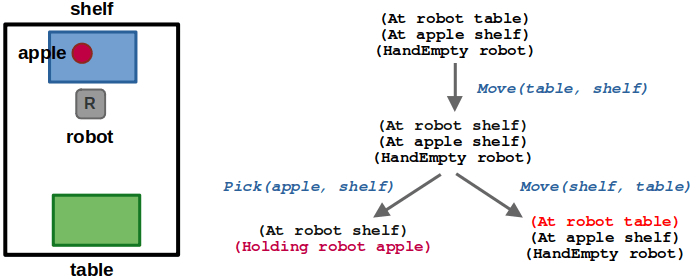

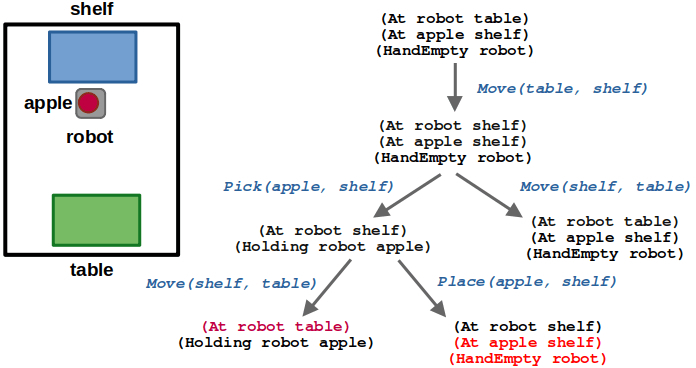

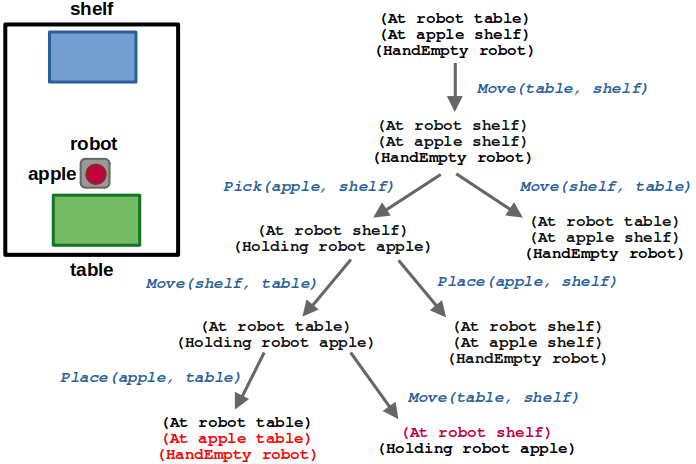

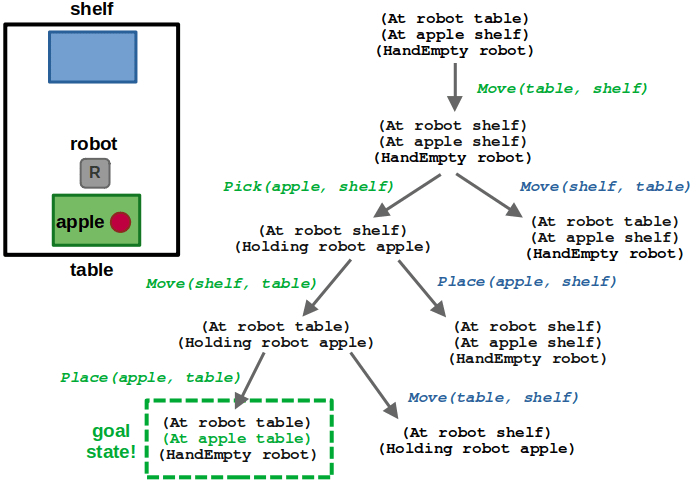

Using our example, let’s see how forward state-space search would work given the goal specification (At apple table):

(1/6) In our simple world, the robot starts at the table. The only valid action from here is to move to the shelf.

(2/6) After moving to the shelf, the robot could either pick the apple or move back to the table. Since moving back to the table leads us to a state we have already seen, we can ignore it.

(3/6) After picking the apple, we could move back to the table or place the apple back on the shelf. Again, placing the apple would lead us to an already visited state.

(4/6) Once the robot is at the table while holding the apple, we can place the apple on the table or move back to the shelf.

(5/6) At this point, if we place the apple on the table we reach a goal state! The sequence of actions leading to the state is our resulting plan.

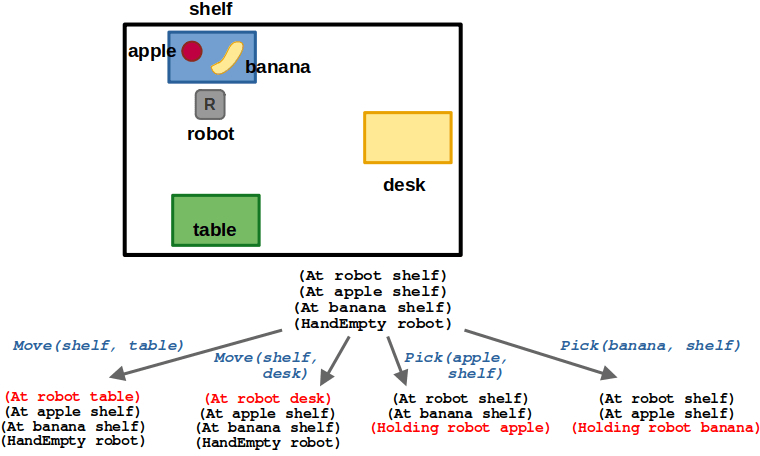

(6/6) As the number of variables increases, the search problem (and time to find a solution) grows exponentially.

Deciding which states to expand during search could be purely based on a predetermined traversal strategy, using standard approaches like breadth-first search (BFS), depth-first search (DFS), and the like. Whether we decide to add costs to actions or treat them all as unit cost (that is, an optimal plan simply minimizes the total number of actions), we could instead decide to use greedy or hill-climbing algorithms to expand the next state based on minimum cost. And finally, regardless of which algorithm we use, we probably want to keep track of states we have already previously visited and prune our search graph to prevent infinite cycles and expanding unnecessary actions.

In motion planning, we often use heuristics during search; one common example is the use of A* with the straight-line distance to a goal as an admissible heuristic. But what is a good heuristic in the context of task planning? How would you define the distance to a goal state without a handy metric like distance? Indeed, a great portion of the literature focuses on just this. Methods like Heuristic Search Planning (HSP) and Fast-Forward (FF) seek to define heuristics by solving relaxed versions of the problem, which includes removing preconditions or negative effects of actions. The de facto standard for state-space search today is a variant of these methods named Fast Downward, whose heuristic relies on building a causal graph to decompose the problem hierarchically — effectively taking the computational hit up front to transform the problem into a handful of approximate but smaller problems that proves itself worthwhile in practice.

Below is an example using pyrobosim and the PDDLStream planning framework, which specifies a more complex goal that uses the predicates we described above. Compared to our example in this post, the video below has a few subtle differences in that there is a separate class of objects to represent the rooms that the robot can navigate, and locations can have multiple placement areas (for example, the counter has separate left and right areas).

- (At robot bedroom)

- (At apple0 table0_tabletop)

- (At banana0 counter0_left)

- (Holding robot water0)

pyrobosim example showing a plan that sequences navigation, pick, and place actions.

Alternative search methods

While forward state-space search is one of the most common ways to plan, it is not the only one. There are many alternative search methods that seek to build alternate data structures whose goal is to avoid the computational complexity of expanding a full state-transition model as above. Some common methods and terms you will see include:

- Plan-space planning (PSP): see these slides for a good example

- Planning graphs: most notably the Graphplan algorithm

- Partial-order planning: most notably the Partial Order Planning Forwards (POPF) algorithm.

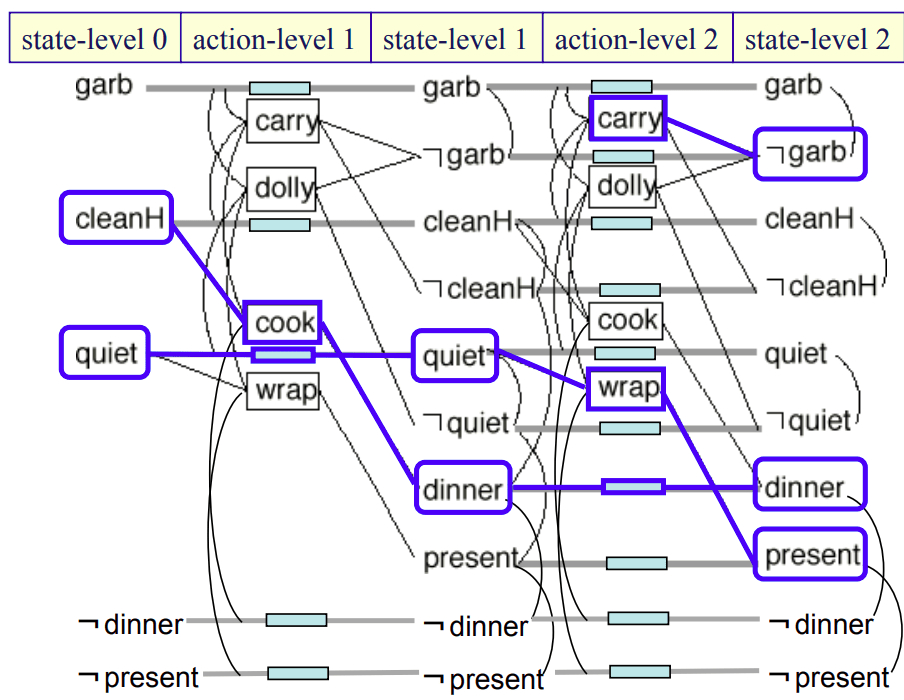

In general, these search methods tend to outperform state-space search in tasks where there are several actions that can be performed in any order relative to each other because they depend on, and affect, mutually exclusive parts of the world. One of the canonical simple examples is the “dinner date example” which is used to demonstrate Graphplan. While these slides describe the problem in more detail, the idea is that a person is preparing a dinner date where the end goal is that dinner and a present be ready while the house is clean — or (dinner present ¬garb). By thinking about the problem in this planning graph structure, we can gain the following insights:

- Planning seeks to find actions that can be executed independently because they are mutually exclusive (mutex). This where the notion of partial ordering comes in, and why there are computational gains compared to explicit state-space search: Instead of separately searching through alternate paths where one action occurs before the other, here we simply say that the actions are mutex and we can figure out which to execute first after planning is complete.

- This problem cannot be solved at one level because cooking requires clean hands (cleanH) and wrapping the present requires quiet, whereas the two methods of taking out the garbage (carry and dolly) negate these predicates, respectively. So in the solution below, we must expand two levels of the planning graph and then backtrack to get a concrete plan. We first execute cook to remove the requirement on cleanH, and then perform the other two actions in any order — it does not matter.

- There is an alternative solution where at the first level we execute the wrap action, and at the second level we can execute cook and dolly (in either order) to achieve the goal. You can imagine this solution would be favored if we additionally required our dinner date hero to have clean hands before starting their date — gross!

Planning graph for the dinner date problem [Source].

Straight lines are preconditions and effects, lines with boxes are no-operation (no-op) links, and curved lines are mutual exclusion (mutex) links.

One solution to the problem is highlighted in blue by backtracking from the goal state.

Towards more complex tasks

Let’s get back to our mobile robot example. What if we want to describe more complex action preconditions and/or goal specifications? After all, we established at the start of this post that simple tasks probably don’t need the giant hammer that is a task planner. For example, instead of requesting that a specific object be placed at a specific location, we could move towards something more general like “all apples should be on the table”.

New example world containing objects, apple0 and apple1, which belong to the same object type (apple).

To explore this, let’s add predicates denoting objects belonging to categories. For example, (Type ?t) can define a specific type and (Is ?o ?t) to denote that an object belongs to such a type. Concretely, we could say that (Type apple), (Is apple0 apple), and (Is apple1 apple).

We can then add a new derived predicate (Has ?loc ?entity) to complete this. Derived predicates are just syntactic sugar — in this case, it helps us to succinctly define an entire space of possible states from our library of existing predicates. However, it lets us express more elaborate ideas in less text. For example:

- (Has table apple0) is true if the object apple0 is at the location table.

- (Has table apple) is true if at least one object of type apple is at the location table.

If we choose the goal state (Has table apple) for our example, a solution could involve placing either apple0 or apple1 on the table. One implementation of this derived predicate could look as follows, which makes use of the exists keyword in PDDL.

(:derived (Has ?loc ?entity)

(or

; CASE 1: Entity is a specific object instance, e.g.,

; (Has table apple0)

(and (Location ?loc)

(Obj ?entity)

(At ?entity ?loc)

)

; CASE 2: Entity is a specific object category, e.g.,

; (Has table apple)

(exists (?o)

(and (Obj ?o)

(Location ?loc)

(Type ?entity)

(Is ?o ?entity)

(At ?o ?loc)

)

)

)

)

Another example would be a HasAll derived predicate, which is true if and only if a particular location contains every object of a specific category. In other words, if you planned for (HasAll table apple), you would need both apple0 and apple1 to be relocated. This could look as follows, this time making use of the imply keyword in PDDL.

(:derived (HasAll ?loc ?objtype)

(imply

(and (Obj ?o)

(Type ?objtype)

(Is ?o ?objtype))

(and (Location ?loc)

(At ?o ?loc))

)

)

You could imagine also using derived predicates as preconditions for actions, to similarly add abstraction in other parts of the planning pipeline. Imagine a robot that can take out your trash and recycling. A derived predicate could be useful to allow dumping a container into recycling only if all the objects inside the container are made of recyclable material; if there is any non-recyclable object, then the robot can either pick out the violating object(s) or simply toss the container in the trash.

Below is an example from pyrobosim where we command our robot to achieve the following goal, which now uses derived predicates to express locations and objects either as specific instance, or through their types:

- (Has desk0_desktop banana0)

- (Has counter apple1)

- (HasNone bathroom banana)

- (HasAll table water)

pyrobosim example showing task planning with derived predicates.

Conclusion

This post barely scratched the surface of task planning, but also introduced several resources where you can find out more. One central resource I would recommend is the Automated Planning and Acting textbook by Malik Ghallab, Dana Nau, and Paolo Traverso.

Some key takeaways are:

- Task planning requires a good model and modeling language to let us describe a task-agnostic planning framework that can be applied to several tasks.

- Task planning is search, where the output is a plan, or a sequence of actions.

- State-space search relies on clever heuristics to work in practice, but there are alternative partial-order methods that aim to make search tractable in a different way.

- PDDL is one of the most common languages used in task planning, where a domain is defined as the tool to solve several problems comprising a set of objects, initial state, and goal specification.

- PDDL is not the only way to formalize task planning. Here are a few papers I enjoyed:

- Task Planning in Robotics: an Empirical Comparison of PDDL-based and ASP-based Systems by Jiang et al. (2018) discusses Answer Set Programming (ASP) in addition to PDDL, but also is a fantastic introduction to task planning in general.

- Towards Manipulation Planning with Temporal Logic Specifications by He et al. (2015) introduces problems similar to our examples, but search is based on automata synthesized from Linear Temporal Logic (LTL) specifications.

After reading this post, the following should now make a little more sense: Some of the more recent task planning systems geared towards robotics, such as the ROS2 Planning System (PlanSys2) and PDDLStream, leverage some of these planners mentioned above. Specifically, these use Fast Downward and POPF.

One key pitfall of task planning — at least in how we’ve seen it so far — is that we are operating at a level of abstraction that is not necessarily ideal for real-world tasks. Let’s consider these hypothetical scenarios:

- If a plan involves navigating between two rooms, but the rooms are not connected or the robot is too large to pass through, how we do know this before we’re actually executing the plan?

- If a plan involves placing 3 objects on a table, but the objects physically will not fit on that table, how do we account for this? And what if there is some other combination of objects that does fit and does satisfy our goal?

To address these scenarios, there possibly is a way to introduce more expert knowledge to our domain as new predicates to use in action preconditions. Another is to consider a richer space of action parameters that reasons about metric details (e.g., specific poses or paths to a goal) more so than a purely symbolic domain would. In both cases, we are thinking more about action feasibility in task planning. This leads us to the field commonly known as task and motion planning (TAMP), and will be the focus of the next post — so stay tuned!

In the meantime, if you want to explore the mobile robot examples in this post, check out my pyrobosim repository and take a look at the task and motion planning documentation.

You can read the original article at Roboticseabass.com.