Robohub.org

Why Google’s robot personality patent isn’t what it appears to be

Google’s new patent: Less about creating robot personalities than collecting yours.

Google’s new patent: Less about creating robot personalities than collecting yours.

Now, I don’t know about you, but a patent on personality seems like a patent on DNA, as if Google had announced, “All your souls are belong to us.” It made me a little jumpy because my company writes personalities for voice-control systems, be they robot, IoT appliances or avatars. Maybe, I thought, this will stunt the growth of the robotics industry and we will finally be faced with Evil.

What about all the people developing robots? Maybe they would save us. Maybe, on the other hand, all the heroic robots from 1970s would save us. A robotic personality isn’t a new concept, afterall.

I wasn’t the only one to sit up and raise an eyebrow. To get a sense of perspective I asked Alexander Reben (robotics artist and engineer) what he thought. He replied, via email, that “what Google has laid out in this patent appears to almost define the field of social robotics. It seems to be quite broad claiming to cover aspects which maybe obvious to those in the field.” Kate Darling (researcher of robot ethics and intellectual property) also thought it was quite broad.

Diana Cooper, who specializes in the legalities and and ethics of robotics (she’s Head of UAS and Robotics Practice Group at LaBarge Weinstein), was more optimistic. She wrote, “I can see this technology being very beneficial, particularly when robots are tasked with assisting in providing treatment to vulnerable populations such as children with disabilities. On a broader scale, I am optimistic that the personalization of robots will counteract society’s anxiety about robots and lead to increased consumer adoption.”

Andra Keay, of Silicon Valley Robotics, pointed out, “I think that Google are a little confused about what a robot is. To quote from one section of the patent: ‘something with processing capabilities and sensors‘ … If there weren’t pictures, I’d have assumed the patent was describing a phone or tablet.”

Personality, like the GUI, is a user interface.

However you want to think about it, the patent was issued. So there it is.

Personality is core to user interface. Personality is – like the graphic design of a GUI – the element that not only allows the sorting and categorization of information but also allows a person to emotionally bond with a robot (or avatar or talking IoT appliance or car or whatever). Personality in a video game interface is different from personality in a business SAAS. Personality also squats at the very foundation of affective computing, human-machine interaction, and even human-human interaction.

When it comes to robots, personality might actually BE interface. If I walk into a hotel room and there’s a robot waiting to greet me, its personality will frame what we do together. If it says “Good afternoon. Would you care to order something from room service?” that’s a very different system than if it says, “Yo! Wanna throw back a few vodkas and play Call of Duty!?” Personality interface, like graphical interface, frames user interaction.

Why This Invention Is Not Patenting Personality

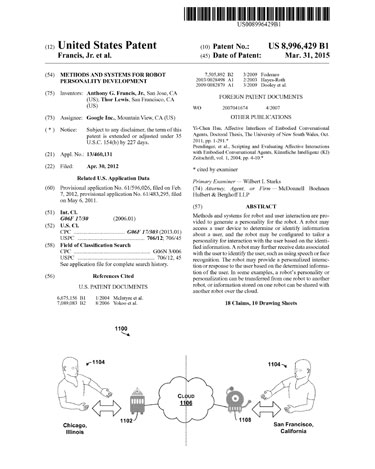

Titled, “Methods and systems for robot personality development” the patent (#US8996429B1 issued by the USPTO on March 31st, 2015) was authored by two employees at Google, one a researcher (Anthony G. Francis, Jr.), the other an R&D UX Creative Lead (Thor Lewis). Knowing their past work is important for understanding this invention – and what place the patent has in our emerging robotics ecosystem.

First, according to the work of Francis (a PhD in AI from Georgia Institute of Tech), context influences how we act. Context is something that allows us to remember, reason and then expend energy appropriately. It allows us to make the right decision at the right time. The context of a task guides its action. Francis has also spent a good deal of time looking into affective computing. And it just so happens that he’s a science fiction author.Second, Lewis (artist, 3D modeler, designer, and science fiction buff, himself), has authored other patents based around machine vision, and came to the world of AI vision from the inside out. He went from making visual things with computers to making computers visual things.

So these two get together and we may imagine their conversation in the Google Coffee shop one afternoon:

“Hey, if a robot can see a thing, like a person, and build context, then doesn’t that inform what the robot does?”

“Yeah, and maybe the robot can get a sense of who that person is based on the stored personal information via their online accounts.”

“Sure, so if the person is at a wedding or a funeral and that would change the way the robot would interact with them, right?”

“Right, and it could remember its past personalities and interactions!”

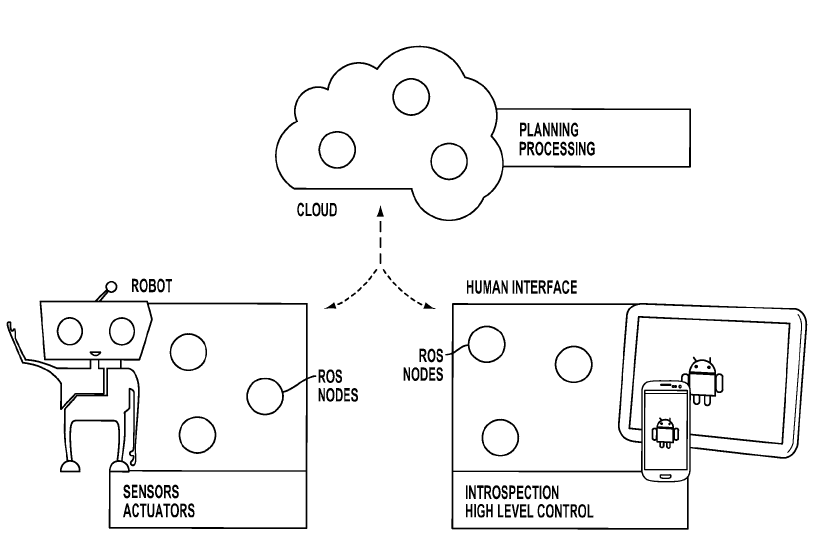

“Totally! And it would live in the Cloud!”

“Awesome!”

“Hey, you got a pen?”

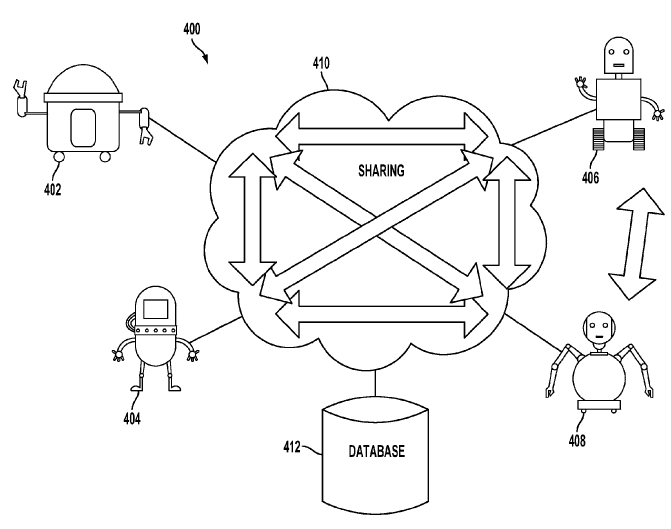

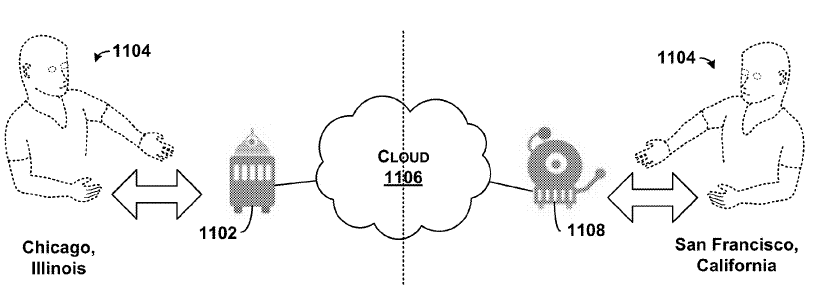

As I read the patent I realized that this isn’t an invention for personality. This is an invention for how to modify a personality in a context. The way that the robot looks, moves, sounds and feels (and touch is mentioned, too), all impact the personality, which can be transferred via the cloud, so personalities can be uploaded, downloaded, shared, and modified. But the patent isn’t as broad as it might first appear. This isn’t inventing personality, per se. It’s inventing how a personality builds context and interacts. The last word of the patent’s title explains that this is not about what personality is, but how personality is developed.

How To Develop A Personality

There are a few pithy lines in the invention. “Personality may be thought of as a personification in the sense of human characteristics or qualities attributed to a non-human thing.” Then the authors set out how those characteristics develop in a context.

Multiple devices are cross-referenced. This allows the robot to collect information on a user and cross-reference data to build context. This means that GoogleBot can now tell that I like to eat cake at a wedding, but not at a funeral, and then modify its personality to align with that context. It will know to offer me cake when people are getting married, not buried.

The patent reviewer, in the “Reasons for Allowance” notes that: “processing to obtain ‘data’ as opposed to information theoretic ‘information’ occurs in response to ‘obtaining’ the information.” This is specifically cited as a part of cloud services as they relate to collecting visual information. Thus the patent differs itself from prior art.

But why would a robot personality development patent be useful to Google? This is core to Google’s advertising business model. GoogleBot will know whether I prefer to eat cereal in the morning or evening, what kind of cereal, what kind of milk, what kind of bowl, what kind of spoon, table, and the timing it takes me to eat that cereal. And just like the business model of web searches from the late 1990s, Google will then be able to sell that data to the many advertisers that support Google’s highly valuable business. Not just cereal of course, but shoes, shirts, shit, shinola and all the other things we consume, produce, and interact with in our daily lives. This context means that the GoogleBot will become one of the most powerful marketing, advertising, and search mechanisms ever built.

A personality that can consolidate our data is one that truly knows us.

GoogleBot’s adaptive personality can consolidate our data and that consolidation knows us. The GoogleBot, with its emphasis on vision, will be able to tell what other cereals I like, what other bowls I use, what other shirts I wear and when I leave for work. By simply observing it will (like search, email, docs, voice, Google+, and the host of other services that Google offers) know me. What is key to context – and to the value of Google’s USD$50 billion-a-year advertising system – is the consolidation of channels of information.

Channel aggregation is a proven and valuable business model. Apple did something similar. When Apple released the iPad (leashed to iTunes and other services), they consolidated the movie channel, the video rental store, the movie theater, and the television into a single device. Apple allowed us to consume more by aggregating media delivery channels.

Apple aggregates output channels to facilitate media sales and Google aggregates input channels to facilitate advertising sales.

Remember that your data is Google’s product, and they sell it to their customers. Imagine a Google Search engine housed in a little teddy bear that modified what it presented based on your past searches. Now imagine that the little teddy bear understood how you felt about those searches, and why. And it told you so, moved, sounded, and even felt a bit different as a result. Now imagine that the context of your search, via this sensitive, sweet robot that is a cuddly animal with an immense, encyclopedic brain, is now completely understanding you and adapting to your needs. Add the Google AdSense, flavor with Google Analytics, stir in Nest, DoubleClick, Uber, 23andMe, residential fiber, and the other Google goodies, and you’ve got something like the Google Panda Robot that was announced the same day the patent was issued (and no, this wasn’t an April fool’s joke). The Amazon Echo appears to be following a similar model, as I mentioned in a previous article.

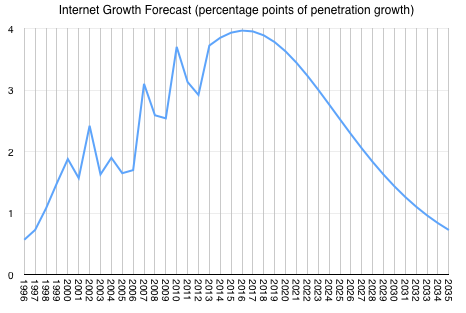

Google has to solve some important problems in the coming year, so this robotics approach is also timely. Internet penetration growth rate is set to peak in 2016. Since Google’s P&L is proportional to Internet usage, they need to invent some new models. Their three existing models – consumer devices, ad-supported consumer services, and software-as-a-service – are approaching maximum impact, and we can expect that they will consolidate all three into this robotic personality that will develop so as to offer each aggregated input channel when it is most contextually appropriate. Google can now consolidate the contexts of buyer-seller to complete the holy circuit of advertise-search. And the context of personality is the interface.

To Know Me is To Own Me

If we thought that value was inherent in goods themselves, then we were wrong. As advertisers have long known, the personal information of what cereal I like is far more valuable than the cereal itself. It will be the opposite of what we thought, especially if what is valuable is what the robot collects. The personal information collected to determine if we like cereal or not will be far more valuable than the cereal itself. So like Shroedinger’s cat, the robot will look for our personality in the box, and our personalities will shift as a result. The context will change and this sensitive interface is will adapt because it was invented to do so. Just like search on Google’s webpage, the robot’s personality is more about collection than display.

Google collects our personalities by cross-referencing our context; this new patent is about cross-referencing context to reflect personalities back to us. And this allows for an improved collection method.

So while Google’s recent patent at first appears to be a method for displaying robot personalities, it is actually a means of collecting our personalities, and therefor our purchasing decisions. It’s not that Google will own our souls, but they will own our personalities, and therefor our decisions.

“All your decisions are belong to us” is writ large upon the sky. But for now this is only a patent, and despite the appearance of the cute teddy-bear robots, our decisions are still left up to us.

At least for now.

If you liked this article, you may also be interested in:

- Why are JIBO, Pepper, Siri, Google Now and Cortana so important?

- The robots behind your Internet shopping addiction: How your wallet is driving retail automation

- Google commits $1.36 billion for NASA facility, to house their robotics, space and flight technologies

- Google news: Rubin leaves; Pichai promoted to #2; and Google invests in Magic Leap

- Google adds to DeepMind, acquiring 2 UK startups and partnering with Oxford U

- Robots Podcast: Privacy, Google, and big deals

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: c-Politics-Law-Society, cx-Consumer-Household, Google, human-robot interaction