Robohub.org

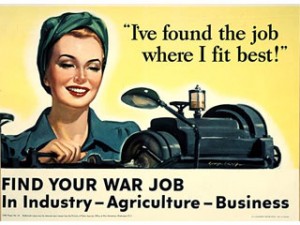

Why isn’t my mother a mechanic?

As a child, my mother had her own overalls. She grew up stripping engines and cleaning carburettors. She was the daughter of a mechanic and master builder. Then she became a librarian.

As a child, I wanted to be an astronaut. I grew up playing with punch cards and radio telescopes. My father was a physicist and astronomer. I built rockets, robots, computers and oscilloscopes with him. Then I became a film maker.

Eventually I returned to the study of rockets and robots but from the perspective of trying to understand why our sciences seemed to be gendered and what happens at the intersections of society and technology.

In Technologies of the Gendered Body, Anne Balsamo wrote “My mother was a computer” to launch a meditation on the gender implications of information technologies as she touches on the changing social status and meaning of occupations. For example, clerking was once a male occupation, now primarily female. And some traditionally female crafts have at times been male only guilds, eg. knitting.

In My Mother Was a Computer, N. Katherine Hayles takes this sentence as her title; ‘as a synecdoche for the panoply of issues raised by the relation of Homo sapiens to Robo sapiens, humans to intelligent machines’. Hayles takes the gender and status implications of our changing technologies in society and raises them to a discussion on our kinship relations to machines, engaging with Moravec’s ‘postbiological’ future.

I love robots because they teach us what it is to be human. Robotics explores our inner space. Our automatons and artificial intelligences imitate life. So we have to work out what it is we are imitating and every choice we make building an imitation being says something about what we think we are, and what we think we aren’t. So who we are, as well as our society, shapes our technologies, while our technologies change the world.

Hayles’ trilogy of books, Writing Machines, How We Became Posthuman and My Mother Was a Computer describe an arc that starts at the binary opposition of embodiment and information, engages with the materiality of literary texts and then extends the ideas of ‘intermediation’ into computation. She takes Latour’s call for a turn from ‘matters of fact’ to ‘matters of concern’ literally, as Hayle’s ‘materiality’ is the intersection between matter and meaning, or “dynamic interactions between physical characteristics and signifying strategies”.

This is a call echoed by Rodney Brooks and Raffaello D’Andrea amongst others, that we start asking social questions more than technological ones in robotics. By extension, a social question is a business one because if someone needs something then they will value it. Not always as highly as they ought, but nonetheless we’ve had enough ‘build it and they will come’! While there are some technical questions (and some people) who are best in an abstract realm, there are many unanswered pragmatic ones.

The materiality of robotics is my area of study, both in the broadest sense of how do some robotic designs come in to being and not others, and also in the minute details of whether or not the materials used in robotics affect the demographics of robot designers.

Robotics is gendered. While women are more equally represented these days in health, medicine and biological sciences, it is clear that engineering and the physical and computing sciences are still heavily male biased. [insert all the books, articles and reports written on gender inequality in STEM here.] This hasn’t changed much over time either. And for the record, this is still the case in politics, finance and business.

I watch this trend up close in Silicon Valley and both the VC and startup worlds are heavily male dominated. It seems as though rapid innovation exacerbates innate biases at a systemic level [insert another long list of articles and books here]. Of course, there are many fabulous women in both startups and in robotics. Of course, some women achieve success, recognition and reward. It’s just that overall, the odds are not in your favor if you are female, and you shouldn’t have to work twice as hard to overcome them. Do you even want to do what so many men do? Maybe some women want different work lives? Maybe some women want different robots?

It’s time to talk more loudly about both gender and biology. I believe that biology plays a strong part in these differences and we risk becoming a society that refuses to talk about difference – because we want to respect everyone’s equality.

Our anodyne culture makes it hard to celebrate different mindedness and different bodiedness. This is worrisome, especially as our ability to tinker with our selves increases. Let’s not do a Dr Lawrence Summers here and shoot the message because we don’t like the messenger.

There are many reasons why women are not in robotics and getting them more engaged in school is only one answer. We must simultaneously address improving the pipeline at every point right up to promotion to CEO or Board, better family life balance, more equitable pay (especially in light of women’s higher rate of p/t or interrupted work), more role models, less innate bias and finally, better value given to areas traditionally female, which will in turn allow more women to import their skills and experience into areas which are, so far, traditionally male.

My mother isn’t a mechanic, but she is a maker. She taught me kitchen chemistry and real cooking. My mother made clothing from necessity and then for pleasure. She taught me 3d modelling, design, aesthetics and problem solving skills in the process. When I was young, I wanted to follow in my father’s footsteps. I wanted to be a physicist, an astronaut, a test fighter pilot and explore outer space.

I gave up when I entered my teens. There was no career pathway for women in space, no role models, no encouragement.

That has changed now, but the deeper lesson I learned was that in the world we have unequal access to technology, by gender or by race or global location. I saw this with the spreading of computer technology and the internet. In some parts of the world you don’t have access to technology — and if you can’t shape the building of new technologies, it’s hard to be an innovator.

Maybe innovation needs more makers and fewer mechanics. Maybe my mother was happy never becoming a mechanic. But she never got the promotions or the pay that she deserved. And her skills as a maker are far less valued than those of a mechanic.

My siblings followed in my father’s footsteps and got PhDs in the ‘hard’ sciences. By contrast, my mother and I are just Masters, and masters of the ‘soft’ sciences. But we are also makers. And I believe that the Maker movement is one way of encouraging us to value more varied contributions to science/technology. At every level of expertise, I would like to see more women making robots, which in turn may lead to more interesting robotics — a robotics that is useful and appealing to the rest of the world.