Robohub.org

Survey shows public attitude towards robotics generally positive, but evokes mixed feelings

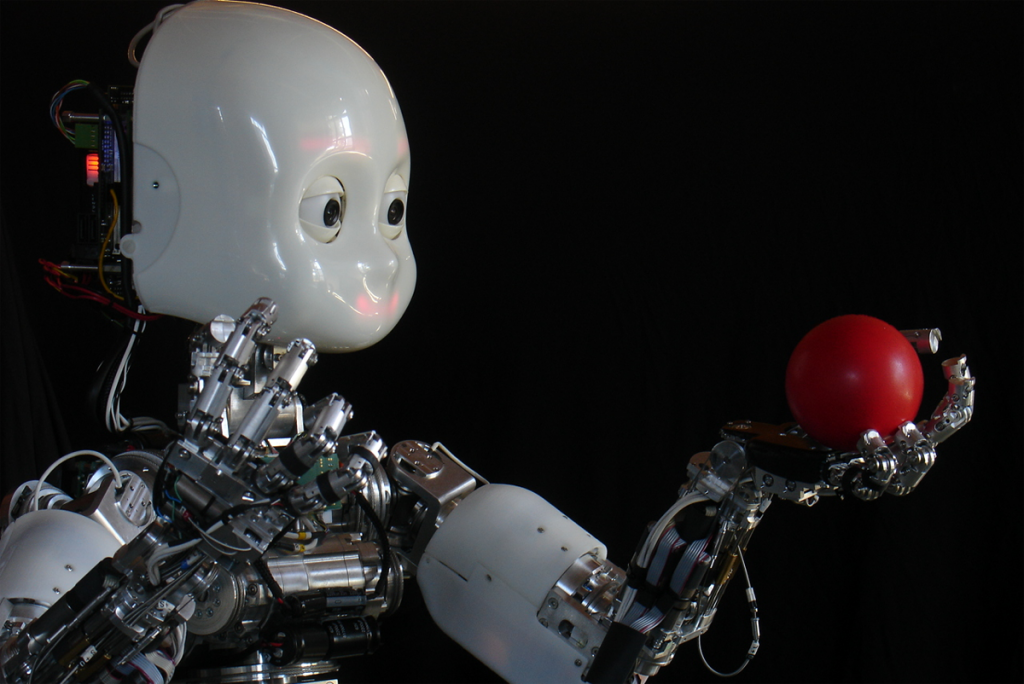

iCub (Image credit: Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia)

The British Science Association released a survey about British public’s attitudes toward robotics and AI. Their headlines state:

- 60% of people think that the use of robots or programmes equipped with artificial intelligence (AI) will lead to fewer jobs within ten years.

- 36% of the public believe that the development of AI poses a threat to the long term survival of humanity.

Other highlights include:

- 46% oppose the idea of robots or AI being programmed with a personality.

We would not trust robots to do some jobs…

- 53% would not trust robots to perform surgery

- 49% would not trust robots to drive public buses

- 62% would not trust trust robots to fly commercial aircraft

However, we would trust them to do…

- 49% want robots to perform domestic tasks for the elderly or the disabled

- 48% want robots to fly unmanned search and rescue missions

- 45% want robots to fly unmanned military aircraft

- 70% want robots to monitor crops

There are also results showing predictable divisions along the lines of gender and age. For example, only 17% of women are optimistic about the development of robots whereas 28% of men are, and 55% of 18-24 year olds could see robots as domestic servants in their household; however, 28% could see having a robot as a co-worker, and 10% could even imagine a robot being a friend.

The UK-RAS network issued a reply by saying while there is need to examine these issues and carefully plan our future, there’s nothing to worry about. They cite a European Commission report showing there is no evidence for automatisation having a negative (or a positive) impact on levels of human employment, pointing to genuine benefits of robots in the workplace about how robots ‘‘can help protect jobs by preventing manufacturing moving from the UK to other countries, and by creating new skilled jobs related to building and servicing these systems.’’

The popular press also seized upon the issue of robots and AI replacing human labour – though a lot of this in recent weeks has been in response to other studies and speeches.

What does this survey tell us

Simply, there is still a problem with people’s perceptions of robotics and AI that must be addressed and it seems we are not heading in the right direction. A Eurobarometer survey on the public’s attitudes to robotics conducted in late 2014 shows that 64% had a generally positive view of robots (which, if added to the 36% in the BSA survey that believes robots and AI are a threat to the future of humanity, just about accounts for everyone). In that 2014 study, however, 36% of respondents thought a robot could do their job and only 4% thought a robot could fully replace them. Clearly this is area of heightened concern.

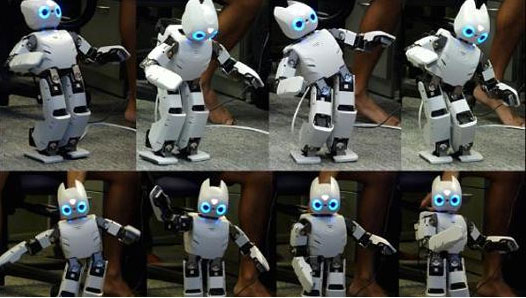

A Robear robot developed by state-backed research institute Riken can lift a person into and out of bed, potentially offering great help to increasingly aging care workers. | RIKEN

A 2013 Sciencewise survey reported almost exactly the same general results: 67% held a generally positive view, though reports 90% would be uncomfortable with the idea of children or elderly parents being cared for by a robot. Compared to the 49% that want robots to help take care of the disabled and elderly in the latest study there might be some progress there. Or people are so desperate to deal with an increasingly ageing population they’re happy to dispense with caring for elderly relatives. However, a 2012 Eurobarometer report told us that 70% of Europeans were generally positive about robots.

it shows there has been little movement in attitudes towards robotics, and in fact an increase in anxiety that robots will displace more humans in the workforce

These comparisons are very rough and cannot tell us much without more rigorous analyses (and the BSA hasn’t provided a link to the full survey). It does it show there has been little movement in attitudes towards robotics, and perhaps an increase in anxiety that robots will displace more humans in the workforce. Without more specific scrutiny it’s hard to say what we’ve got here. It could well be the case that what we have is unremarkable. Though it may be encouraging to see that a majority of Europeans are consistently positive in their perception of robots and AI, there is still a sizeable minority that could prove very disruptive to the development of future applications of robotics and AI, whose anxieties cannot – and should not – be ignored.

One way to alleviate a great deal of these concerns, particularly regarding the loss of jobs, is to explicitly address the vital question in the public imagination: what does this increasing automatisation mean in societies? Because it is not in any way inevitable that more working robots and AI means more poverty for unemployed humans. We get to choose what the consequences are of this mechanisation; these decisions will be taken by human beings and not left to the whims of sentient robots or even the indifference of disembodied market forces. If we decide to divide the advantages of automatisation more equally (for example, with the introduction of a Universal Basic Income), then it could be a very good thing indeed.

Again, without more scrutiny, it is difficult to judge what these numbers mean. It seems to suggest that the public are very ambivalent about the forthcoming developments in robotics and AI: if 46% oppose the idea of robots or AI being programmed with a personality, then it could mean that around 54% of people could be perfectly fine with emotionally engaged robots. If half of us don’t want robots driving public buses (49%, according to the BSA survey), half might be happy for the them to do so.

We might look at this study and say that we are ambivalent about robots and AI – that means, not ‘indifferent’ (as ambivalent is often, incorrectly, taken to mean now), but that we have mixed feelings. However, this could be a terrible misreading of the numbers. What if people aren’t deeply ambivalent, but radically schizophrenic? If 50% are reporting that they are worried the other 50% might not be – they might even be enthusiastic about future possibilities.

Professor scientist and a robot.

Again, there is no evidence in this study to support this notion, necessarily. There is clearly a need for more research into the specific concerns – and their sources – in order to properly address these issues, and to understand these anxieties more thoroughly (which will need a very different sort of study). However, the majority of cultural record offers some unique insights: sci-fi films show us that we are not at all indifferent to robots and AI, or ambivalent. There is no middle ground. When it comes to robots and AI we are either deeply terrified OR wildly optimistic. We seem to be convinced robots will either spell certain doom for the human race or our last, our greatest, hope for salvation from all of the terrible things that threaten us (including, inevitably, other robots and ourselves).

Such diametrically opposed perceptions – such dread or aspiration – do not facilitate the sort of reasoned, rational, debate that will be necessary to properly assess both the challenges and the opportunities that real robots and AI represent, outside the pages and reels of science fiction.

tags: c-Politics-Law-Society