Robohub.org

Robohub turns three!

Robohub turns three today, and what a year it’s been! Just last month we got our 7000th twitter follower, saw a viral post garner over 18K page views, and launched two new video series (here and here). All this momentum is no doubt thanks to the many, many incredible volunteers who dedicate their time and energy to contributing content and making Robohub happen. Earlier this year our co-founder Sabine Hauert was invited to contribute a commentary in Nature about why good science communication is so important to robotics and AI. We’ve elaborated on that article below.

Robohub turns three today, and what a year it’s been! Just last month we got our 7000th twitter follower, saw a viral post garner over 18K page views, and launched two new video series (here and here). All this momentum is no doubt thanks to the many, many incredible volunteers who dedicate their time and energy to contributing content and making Robohub happen. Earlier this year our co-founder Sabine Hauert was invited to contribute a commentary in Nature about why good science communication is so important to robotics and AI. We’ve elaborated on that article below.

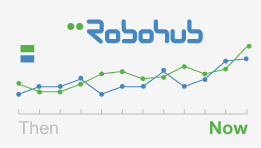

938 unique visitors in 09/2012

21,238 unique visitors in 09/2013

49,926 unique visitors in 09/2014

80,772 unique visitors in 09/201515 contributors as of 09/2012

66 contributors as of 09/2013

148 contributors as of 09/2014

300+ contributors as of 09/2014Most popular posts in our 3rd year

- Watch flying machines weave a rope bridge you can walk on

- Artificial General Intelligence that plays Atari video games: How did DeepMind do it?

- Why is Japan the first to get Dyson’s new 360 Eye?

Focus series launched in our 3rd year

Reducing the hype by becoming the messenger

[An adapted version was first published in Nature, 521, 415–418, 2015, by Nature Publishing Group.]

There was a recent article entitled “Hunting as a pack” about my work simulating nanoparticles to treat cancer. I immediately received a worried email from a colleague about the risk that the public would be reminded of nanobots that take over the world. The article was good, but the title was hype.

The reality is that it happens all the time: hyped headlines lead readers to fear or over-inflate their expectations of robotics, and usually experts blame the media. Often the reaction is to stop communicating with the public altogether.

The problem is that the public includes taxpayers, policy makers, investors, and those who could benefit from the technology. What they often hear is a one-sided discussion about the latest in robotics that leaves them worried about their jobs, and fearful of AI. Policy makers consider laws that will stifle the development of hypothetical technology, and meanwhile we spend our dinner parties explaining that we are not designing a Terminator robot. This is frustrating for experts who work for years to develop technology that could help us as we grow old, improve our healthcare, make our daily jobs safer, and more efficient, and allow us to explore new frontiers in space or beneath the oceans.

What’s the solution to all the hype about robots? I believe that robotics experts need to be messengers. With the advent of social media, experts now have a direct channel to the public and can use it to provide expert views and help drive a balanced discussion. We can talk about the latest developments and limitations, provide the big picture, and demystify the technology. It’s also a great way to drive crowdfunding campaigns, recruit future students, and connect with colleagues. I recruited my first PhD student through social media!

Why aren’t we doing it more? First, many experts have never tweeted, blogged, or made a YouTube video. Second, it’s seen as “yet another thing to do”, and experts don’t have any extra time. Third, it takes years to build a following that makes the effort worthwhile.

Empowering robotics and AI professionals to communicate will therefore require training, support, and incentives. The first step is to provide crash-courses in science communication, such as the ICRA 2015 social media workshop that Robohub organized this year to teach the basics about how to produce regular content on social media with minimal time commitment.

We also make communication easy by taking video cameras to conferences to capture research results and technology spotlights; it takes experts who are already presenting at the conference less than five minutes to stand in front of the camera and pitch their work to the public – and the results are easily uploaded to YouTube, where their work suddenly gains far greater reach (remember our webcams at ICRA and IROS?). We also welcome articles, opinions, and crowdfunding pitches directly written by the experts.

We also make communication easy by taking video cameras to conferences to capture research results and technology spotlights; it takes experts who are already presenting at the conference less than five minutes to stand in front of the camera and pitch their work to the public – and the results are easily uploaded to YouTube, where their work suddenly gains far greater reach (remember our webcams at ICRA and IROS?). We also welcome articles, opinions, and crowdfunding pitches directly written by the experts.

Professional science communicators and journalists are brought in to help shape the messages, make them clear and concise, and avoid pitfalls. The trick here is to make sure the expert is driving the story with the help of an expert communicator, rather than having the communicator running the show. Models like The Conversation — a news website that only publishes content written by academics — do this very well, and we strive to emanate this. The end result is an article that the expert wants to feature on their homepage, because they feel it does a good job explaining their work.

How is Robohub doing? Take our annual reader survey!

And finally, thanks to you, our readers, we’ve also built a strong dissemination pipeline, so that anyone who blogs or tweets in their corner is relayed through a common portal that amplifies their reach to tens of thousands of followers.

While I can list all the benefits of science communication, the incentive really needs to come from the main stakeholders in robotics, such as funding agencies and institutes. If citations are the measure of success for grants and academic progression, how can we also value shares, views, comments, or likes? Rodney Brooks’ famous work on the subsumption architecture gathered nearly 10,000 citations in roughly 30 years; the video of his latest robot Sawyer garnered over 60,000 views in one month.

Which one will have more impact in today’s public discourse?

Stakeholders have shown a clear interest in outreach and science communication, requesting dedicated sections in grant proposals and allocating funding for communication efforts. Each project typically develops its own strategy, resulting in pockets of communication that have limited reach.

If every funding agency in the world gave 0.1% of their funding to an effort to bring together these disjointed communications, we could speak more loudly. If we could build a common strategy around training, support, and incentives that is centered around the idea of experts as communicators, we could empower a future generation of roboticists that are deeply connected to the public and able to hold their own in a discussion about the future of robotics and AI.

Not every expert needs to be a communicator, but if enough of us are, we can make the voice of our community heard. This is essential if we are to prevent misconceptions from driving policy, funding decisions, and public perception.

Robohub is a community, and a community’s strength lies in its engagement. Here’s what you can do to get involved:

- Sponsor a focus series. Does your industry, research group, or association have something important to share? A sponsored focus series is a great way to create a conversation around a dedicated topic and generate awareness about emerging technologies and issues.

- Let us drive communication for your organization. Does your organization need help communicating? We can provide a web infrastructure and dedicated content in collaboration with your team.

- Hire us to give a communications workshop. Our top notch team of science communicators can train your organization on how to communicate about robotics effectively and use social media to your advantage.

- Become a contributor. If you are an expert in some aspect of robotics, then we want to hear from you!

- Spread the word. Like us! Join our circle! Tweet our stories! Upvote!

- Go ahead and republish. Robohub believes in the free flow of information, so unless otherwise noted, you can republish our articles online or in print for free as long as you don’t edit or sell them separately.

- Donate. Robohub is non-profit and relies on support from grants and from the community. Your donations help us pay the salaries of our dedicated staff, maintain the website and explore new content initiatives.

- Fill out our annual reader survey. Your feedback will help us as we apply for grants and philanthropic sponsors to support Robohub.

Thanks to all our readers and contributors for making it such a great year! Here’s to many more.

tags: communicating robotics