Robohub.org

Robotic cubes shapeshift in outer space

MIT PhD student Martin Nisser tests self-reconfiguring robot blocks, or ElectroVoxels, in microgravity. Photo: Steve Boxall/ZeroG

By Rachel Gordon | MIT CSAIL

If faced with the choice of sending a swarm of full-sized, distinct robots to space, or a large crew of smaller robotic modules, you might want to enlist the latter. Modular robots, like those depicted in films such as “Big Hero 6,” hold a special type of promise for their self-assembling and reconfiguring abilities. But for all of the ambitious desire for fast, reliable deployment in domains extending to space exploration, search and rescue, and shape-shifting, modular robots built to date are still a little clunky. They’re typically built from a menagerie of large, expensive motors to facilitate movement, calling for a much-needed focus on more scalable architectures — both up in quantity and down in size.

Scientists from MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) called on electromagnetism — electromagnetic fields generated by the movement of electric current — to avoid the usual stuffing of bulky and expensive actuators into individual blocks. Instead, they embedded small, easily manufactured, inexpensive electromagnets into the edges of the cubes that repel and attract, allowing the robots to spin and move around each other and rapidly change shape.

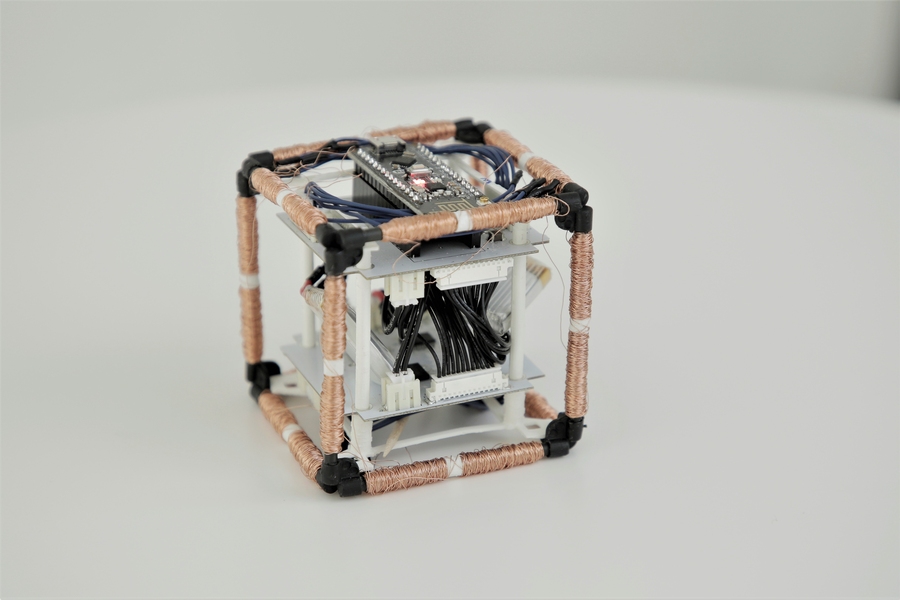

The “ElectroVoxels” have a side length of about 60 millimeters, and the magnets consist of ferrite core (they look like little black tubes) wrapped with copper wire, totaling a whopping cost of just 60 cents. Inside each cube are tiny printed circuit boards and electronics that send current through the right electromagnet in the right direction.

Unlike traditional hinges that require mechanical attachments between two elements, ElectroVoxels are completely wireless, making it much easier to maintain and manufacture for a large-scale system.

ElectroVoxels are robotic cubes that can reconfigure using electromagnets. The cubes don’t need motors or propellant to move, and can operate in microgravity.

To better visualize what a bunch of blocks would look like while interacting, the scientists used a software planner that visualizes reconfigurations and computes the underlying electromagnetic assignments. A user can manipulate up to a thousand cubes with just a few clicks, or use predefined scripts that encode multiple, consecutive rotations. The system really lets the user drive the fate of the blocks, within reason — you can change the speed, highlight the magnets, and display necessary moves to avoid collisions. You can instruct the blocks to take on different shapes (like a chair to a couch, because who needs both?)

The cheap little blocks are particularly auspicious for microgravity environments, where any structure that you want to launch to orbit needs to fit inside the rocket used to launch it. After initial tests on an air table, ElextroVoxels found true weightlessness when tested in a microgravity flight, with the overall impetus of better space exploration tools like propellant-free reconfiguration or changing the inertia properties of a spacecraft.

By leveraging propellant-free actuation, for example, there’s no need to launch extra fuel for reconfiguration, which addresses many of the challenges associated with launch mass and volume. The hope, then, is that this reconfigurability method could aid myriad future space endeavors: augmentation and replacement of space structures over multiple launches, temporary structures to help with spacecraft inspection and astronaut assistance, and (future iterations) of the cubes acting as self-sorting storage containers.

“ElectroVoxels show how to engineer a fully reconfigurable system, and exposes our scientific community to the challenges that need to be tackled to have a fully functional modular robotic system in orbit,” says Dario Izzo, head of the Advanced Concepts Team at the European Space Agency. “This research demonstrates how electromagnetically actuated pivoting cubes are simple to build, operate, and maintain, enabling a flexible, modular and reconfigurable system that can serve as an inspiration to design intelligent components of future exploration missions.”

To make the blocks move, they have to follow a sequence, like little homogeneous Tetris pieces. In this case, there are three steps to the polarization sequence: launch, travel, and catch, with each phase having a traveling cube (for moving), an origin one (where the traveling cube launches), and destination (which catches the traveling cube). Users of the software can specify which cube to pivot in what direction, and the algorithm will automatically compute the sequence and address of electromagnetic assignments required to make that happen (repel, attract, or turn off).

For future work, moving from space to Earth is the natural next step for ElectroVoxels, which would require doing more detailed modeling and optimization of these electromagnets to do reconfiguration against gravity here.

“When building a large, complex structure, you don’t want to be constrained by the availability and expertise of people assembling it, the size of your transportation vehicle, or the adverse environmental conditions of the assembly site. While these axioms hold true on Earth, they compound severely for building things in space,” says MIT CSAIL PhD student Martin Nisser, the lead author on a paper about ElectroVoxels. “If you could have structures that assemble themselves from simple, homogeneous modules, you could eliminate a lot of these problems. So while the potential benefits in space are particularly great, the paradox is that the favorable dynamics provided by microgravity mean some of those problems are actually also easier to solve — in space, even tiny forces can make big things move. By applying this technology to solve real near-term problems in space, we can hopefully incubate the technology for future use on earth too.”

Nisser wrote the paper alongside Leon Cheng and Yashaswini Makaram of MIT CSAIL; Ryo Suzuki, assistant professor of computer science at the University of Calgary; and MIT Professor Stefanie Mueller. They will present the work at the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation. The work was supported, in part, by The MIT Space Exploration Initiative.

tags: c-Research-Innovation, modular