Robohub.org

DARPA announces new challenges, teams, and research goals for the DRC’s finale in June 2015

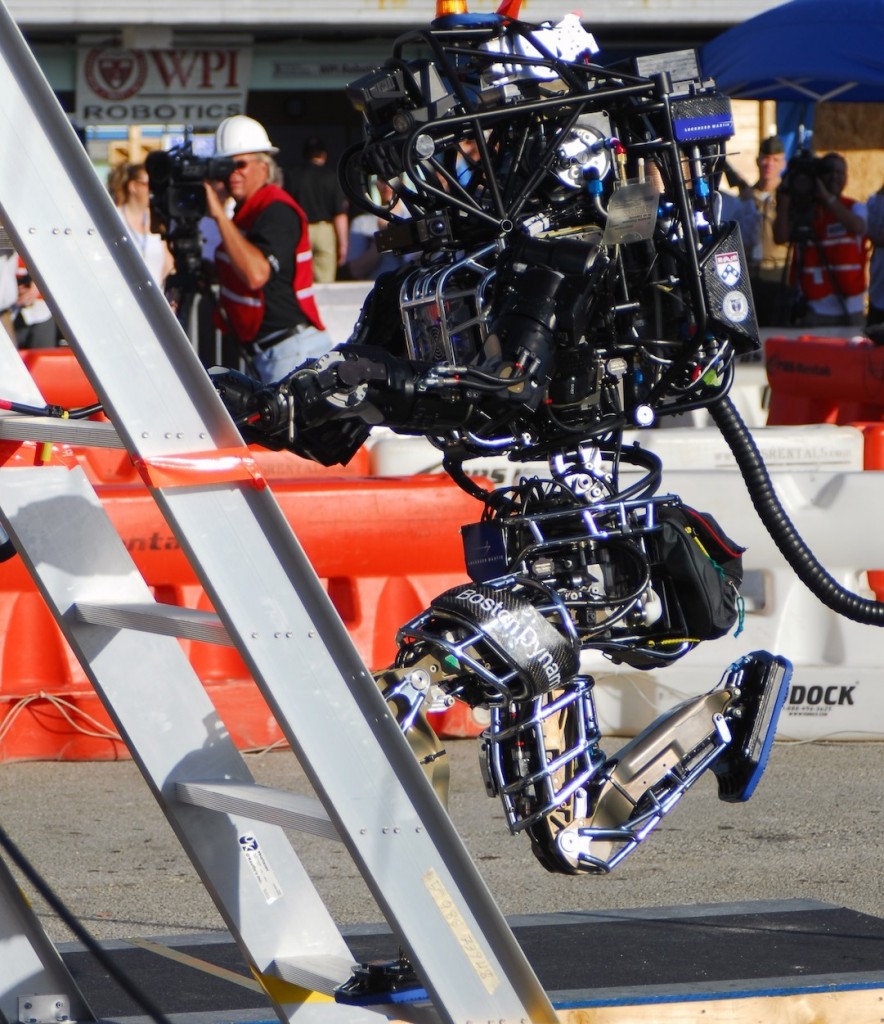

ATLAS climbs a ladder in December’s DRC Trials. Source: DARPA

Teams of roboticists from around the globe will convene in Los Angeles for the third and final round of the DARPA Robotics Challenge on June 5th and 6th, 2015. For this phase, DARPA will be cutting the safety tethers, power cords, and network connections that previously assisted robots. The roster of participants has also changed, with Japan, Korea, and the EU electing to sponsor teams and Team SCHAFT, winners of the last phase, deciding to withdraw from the competition. DRC Program manager Gill Pratt explained that by raising the stakes and expanding participation, DARPA is hoping to foster the development of more advanced autonomous behavior for robots that operate in complex environments.

June 5-6, 2015

Fairplex

Pomona, California

Pre-qualified teams

Team IHMC Robotics

Team KAIST

Team MIT

Team RoboSimian

Team Tartan Rescue

Team THOR

Team TRACLabs

Team Trooper

Team VALOR

Team ViGIR

Team WPI‐CMU

Teams pending qualification

Team HKU

Pratt started the announcement by explaining how the Challenge has already exceeded his expectations. At the DRC Trials held last December (check out our beginner’s guide if this is news to you), organizers expected the winning team could maybe score about 15 points, but four teams exceeded that number and SCHAFT won 27. Now that participants have shown what they’re capable of, DARPA wants to push them further.

He explained that robot hardware was, across the board, robust, and teams did surprisingly well with grasping and dexterity, mobility, and human-robot interface design. But it’s time to solve, in Pratt’s words, “the really hard part of the robotics problem.” He wants humans and robots to be able to collaborate more effectively in the field by leveraging the unique capabilities of both. To see this happen, he’s changing the rules to force teams to rely less upon the remote control of individual joints and motions and instead implement task-based interfaces that incorporate advanced perception, minimal human guidance, and complex autonomous behavior.

The trial will still involve two attempts at eight tasks. But there’s a twist: robots will now only have an hour to perform all eight consecutively. In the last round, robots attempted each stage separately and were allotted 30 minutes for each task. The tasks have yet to be finalized, but details will be sparse until the teams converge in California for the competition. Seven tasks will be derived from the challenges of the last round, but one surprise task will be introduced at the competition. Pratt pointed out that robots will be “at least four times faster than the trials, and perhaps even faster.”

“We think the robot being able to survive a fall is difficult but not too hard. We have little information on the difficulty of getting up. This is a very new thing we’re trying, very high risk, for those machines that do fall down, it’s going to be really neat to see how they handle it, because […] humans will not be able to teleoperate the machine with any reasonable performance.”

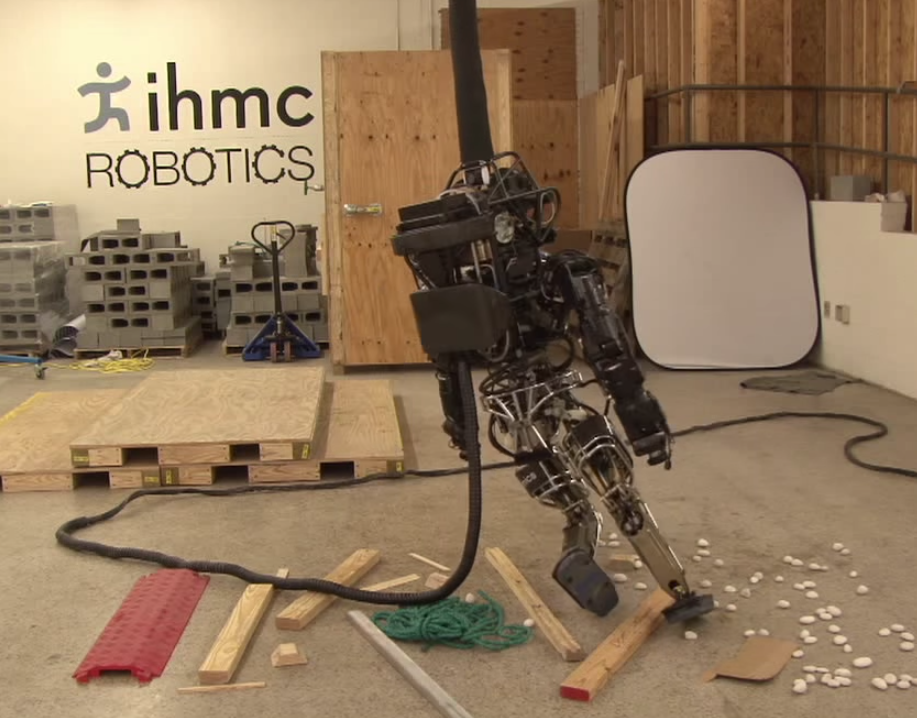

At the DRC trials last December, the robots often moved excruciatingly slow and depended upon the careful control of remote human operators. Even with this divine guidance, they still fell down on their safety tethers quite often. But these handicaps will be gone in the next round. DARPA organizers want to see how well a robot can perform in the field without an umbilical cord, so they’re cutting the robots’ physical and electrical tethers. They’ve also decided that robots will entirely lose their network connection “for a substantial fraction of the time available” explaining this had the goal of preventing direct teleoperation.

In the December trials, robots were connected to tethers that kept them from crashing with the ground. In the next round, robots will lose their leases, fall down, and — hopefully — pick themselves back up. Source: Team IHMC

Pratt explained that these requirements were added to more accurately simulate the challenges faced by disaster robots at Fukushima-Daiichi. Robots depended upon limited battery power and thick concrete and steel-reinforced walls in the plant made network connectivity intermittent at best. And there certainly weren’t any safety lines to prevent the robots from falling.

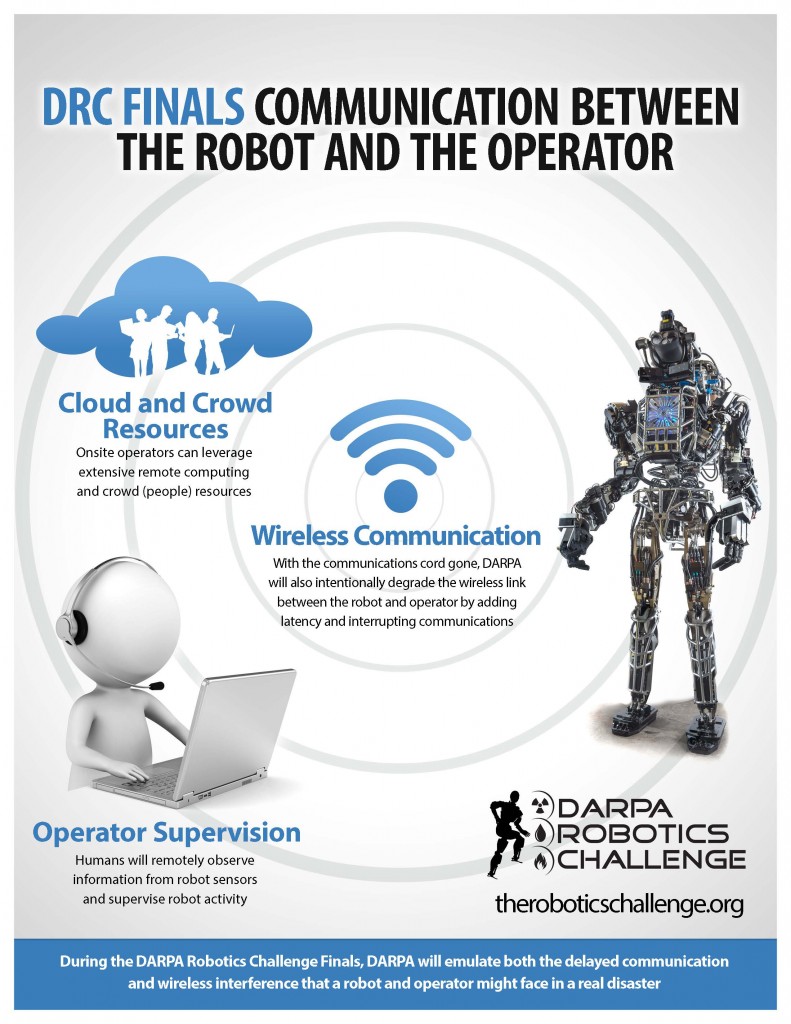

Whenever the robots have a network connection, they’ll have significantly more computing resources than were available in the last round. Organizers are curious about the new paradigm of cloud-assisted autonomy and want to see how it could be used in field robots. So robots will have access to “as much computing power, as much disk space, as much crowd-sourced expertise” as the teams desire. Robots will also be able to connect to the internet. Look for DRC robots to ask for your assistance via Facebook next summer!

In the DRC’s final round, robots will have more resources available via their network connection, but the connection will only be intermittently available. Source: DARPA

Pratt also announced that the governments of Japan, Korea, and The EU are planning to sponsor teams. In light of this funding infusion, and the surprising performance of unfunded teams in the last round, DARPA has invited more teams to join this final round of the competition. Any team that can demonstrate a robot completing several “simple” DRC tasks is invited to submit a video to the DRC website by February 2nd, 2015. Eleven teams are qualified at this moment but organizers are hoping 24 teams will participate next June.

Another important announcement today was the news that Team SCHAFT – winner of the December trials – has withdrawn from the competition to focus on commercializing its technology. Remember that Google acquired SCHAFT last December.

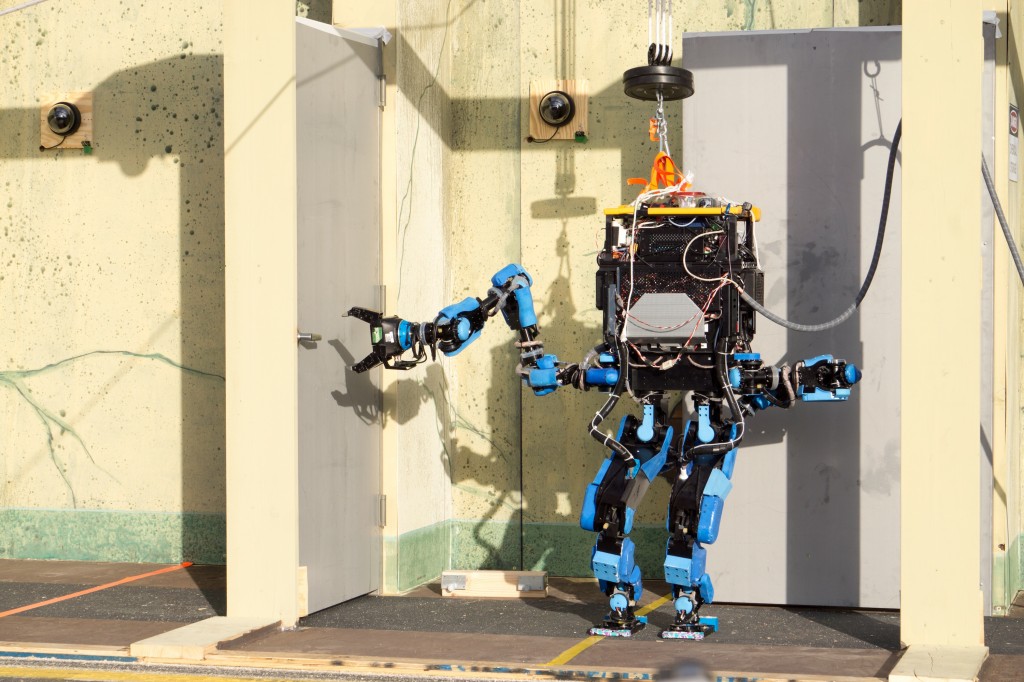

SCHAFT, who won the last round by 7 points, won’t be competing in LA next June. Instead, SCHAFT’s technology might soon appear in a Google robot. Source: DARPA

Considering executives’ assertions that Google had no plans to become a military contractor and the rumor that started circulating in January, SCHAFT’s disaffiliation from DARPA isn’t too surprising. As announced in March, the funding to which SCHAFT was entitled will be distributed among two previously-unfunded teams, THOR and ViGIR.

“[DARPA hopes] companies will pick up the technology developed in the DRC, develop it further, commercialize it, and the results will be cheap enough to make reasonably-priced disaster robots.”

By making the challenge so demanding and offering a $2 million prize, DARPA is hoping to lay the technological foundation for more autonomous and capable robots in the commercial market. In fact, DARPA will measure the success of the competition in part by the commercial investments in robotics that it inspires. To help DRC technology reach the market, DARPA and some participating teams plan to publish the lessons they learned in the challenge in academic journals.

Left: Team Stanford’s Stanley, the winning car of DARPA’s 2005 Grand Challenge.

Right: The Google Car, developed by a team led by Sebastian Thrun, former leader of Team Stanford. Sources: DARPA, Google

It’s reasonable to expect success — by hosting the Grand Challenge in 2003, DARPA turned the key on autonomous vehicles. Google acquired the winning team from Stanford, so you can trace their autonomous car’s lineage back to DARPA. With SCHAFT’s announcement and Google’s acquisitions of it and Boston Dynamics, history is repeating itself. Dr. Pratt’s vision of the DRC’s legacy seems to be materializing before the competition even finishes.

If you liked this article, you may also be interested in:

- DARPA’s Gill Pratt on Google’s robotics investments

- Robots Podcast: The DARPA Robotics Challenge

- Beginner’s guide to the humanoid robot challenge (DRC)

- Robots, soldiers and cyborgs: The future of warfare

- DARPA’s Virtual Robotics Challenge a practical step forward on the long road toward disaster-response capable humanoids

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

For more DRC reading, see our interview with Dr. Pratt.

tags: Boston Dynamics, c-Events, cx-Military-Defense, cx-Research-Innovation, DARPA, DRC