Robohub.org

Robot caregivers: How much interaction with a robot is socially acceptable?

With the continuous increase in life expectancy and the number of people aged 65+ on the rise, it is no wonder that many roboticists have been discussing the use of robot as companion/caregiver for elderly. Here’s a reality check: the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration on Aging projected that by 2030, the number of seniors over 65 will be 72.1 million. That’s 19% of the population – a significant increase from the 13% it was in 2009 (39.6 million). In Japan, the country with the world’s oldest population (22.3% of the population is over 65), the problem of meeting the increased demand of caregiving has been labelled the “Japan elder crisis” and has triggered the launch of many projects to tackle the issue, including substituting/augmenting human caregivers with robotic ones.

One such pioneering project is Paro, a social robot that resembles a baby harp seal. Paro shows promise in lifting the spirits of elderly adults, especially in those patients with dementia or depression. A more recent project is Smiby, a low-tech baby robot developed by Chukyo University’s robotics department in collaboration with Togo Seisakusyo Corporation. Smiby requires human “parents” to attend to it as if it were an infant child, providing its users a sense of companionship, bonding and, hopefully, happiness.

Other robots, such as GeriJoy (USA) and GiraffPlus (EU), aim to reduce feelings of loneliness and isolation.

GeriJoy, a start-up founded by two Massachusetts Institute of Technology researchers, combines pet therapy, avatars and tablet computing to provide virtual pet companions for elderly adults. The caregiver provided by GeriJoy is a trained “helper” located in the Philippines who communicates with elderly clients through an avatar of a cute dog or cat on a tablet app. Streaming audio and visual data help remote caregivers to check on the clients, telling them when to spark up a conversation or prompt their charges to take medication, eat and exercise. GiraffPlus, an EU-based project, is a telepresence robot (consisting of a tablet screen attached to a wheeled cart) that allows caregivers and family members to videoconference with their charges and loved ones.

These fluffy, social, and interactive robots are not without their problems, and bring with them pressing ethical issues for the healthcare community as expressed by a number of experts in the field.

Tom Sorell, a professor of politics and philosophy who leads the Interdisciplinary Ethics Research Group at the University of Warwick in the UK, argues that an ethical framework should be developed for robotic caretakers that respect the elderly person’s autonomy and decision-making. Amanda and Noel Sharkey, computer scientists at the University of Sheffield, have highlighted the need to balance the benefits of robotic companions with the potential risks of treating elderly adults like children, or deceiving those with dementia.

Furthermore, in her latest journal publication, Amanda Sharkey says: “At the same time, insensitive use of assistive robots could have a negative effect on the access of vulnerable seniors to certain capabilities … Increased use of assistive robots in general could lead to a reduced number of interactions with humans, and so reduce older people’s opportunities for social interaction and affiliation with others”.

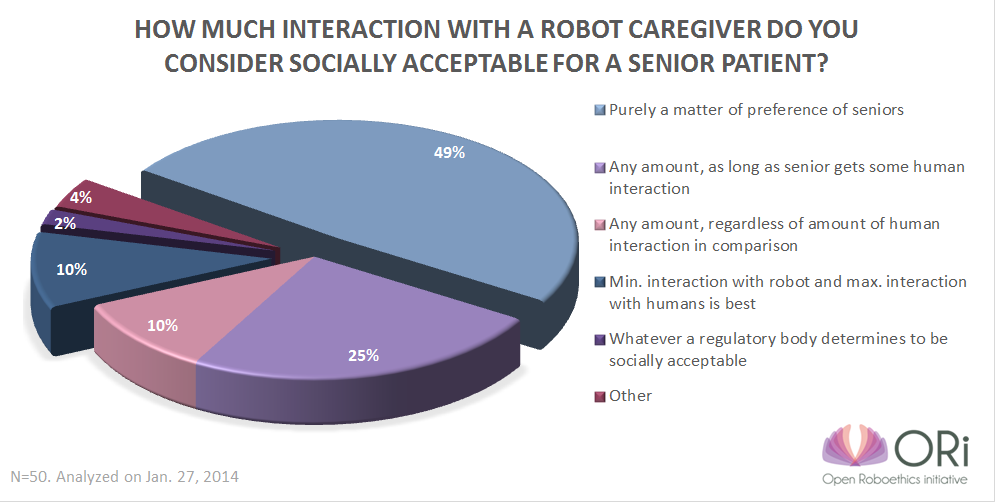

As we continue to explore this topic this, our latest poll question was about how much interaction between a senior and a robot caregiver is socially acceptable. Here are the results:

First, according to the results, our readers do not feel strongly about the need to regulate the amount of interaction seniors have with robot caregivers: almost half (48%) of the respondents said that this is purely a matter of preference of the individual seniors. In addition, 34% of our respondents stated that any amount of interaction with a robot is acceptable, although more people sharing this view qualified this with the phrase “as long as the senior gets some human interaction on a regular basis.”

First, according to the results, our readers do not feel strongly about the need to regulate the amount of interaction seniors have with robot caregivers: almost half (48%) of the respondents said that this is purely a matter of preference of the individual seniors. In addition, 34% of our respondents stated that any amount of interaction with a robot is acceptable, although more people sharing this view qualified this with the phrase “as long as the senior gets some human interaction on a regular basis.”

More interestingly, only 2% of the respondents chose the option that involved a regulatory body to determine the right amount of interaction. Is this because people do not feel that the amount of interaction with robots is something that should be regulated in any way, or because people do not have faith in regulatory bodies to make appropriate decisions for us? The dominant support for the use of senior’s preferences seems to suggest the former. Also worth noting is the fact that only 10% of the respondents said that maximum interaction with humans and minimum interaction with robots is best.

This indicates that the majority of our respondents, most of whom are roboticists or related to robotics in some way, trust seniors to make preferential choices by themselves on this topic, and that the amount of interaction with care robots is not seen to pose a major point of concern.

This question we posed to poll-takers did not take into account the cognitive capabilities of the senior in question. Would our view of how much seniors should interact with care robots change as we consider seniors with varying degrees of cognitive capabilities? And how to address the fact that cognitive abilities deteriorate with age? More for us to think about in a future poll.

Do you have questions or topics you’d like ORi and Robohub to cover in our poll-based discussions? Send us an email (ajung@openroboethics.org).

The results of the poll presented in this post have been analyzed and prepared by Camilla Bassani, with the help of AJung Moon, Shalaleh Rismani, Rohan Nuttall, Joost Hilte, and Julio Vazquez at the Open Roboethics initiative.

tags: c-Politics-Law-Society, cx-Research-Innovation, ethics, human-robot interaction, PARO