Robohub.org

Prepping a robot for its journey to Mars

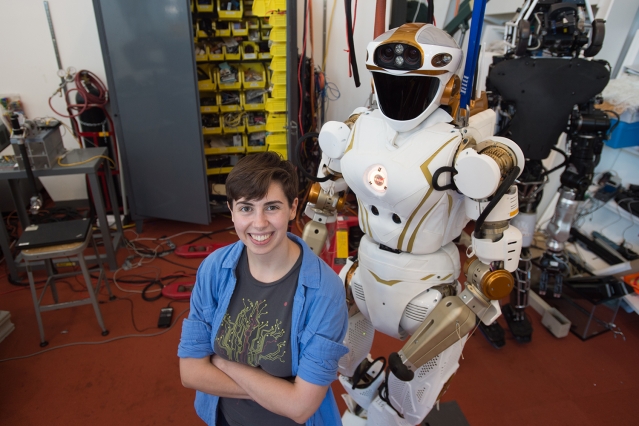

Sarah Hensley is preparing an astronaut named Valkyrie for a mission to Mars. It is 6 feet tall, weighs 300 pounds, and is equipped with an extended chest cavity that makes it look distinctly female. Hensley spends much of her time this semester analyzing the movements of one of Valkyrie’s arms.

As a fourth-year electrical engineering student at MIT, Hensley is working with a team of researchers to prepare Valkyrie, a humanoid robot also known as R5, for future space missions. As a teenager in New Jersey, Hensley loved to read in her downtime, particularly Isaac Asimov’s classic robot series. “I’m a huge science fiction nerd — and now I’m actually getting to work with a robot that’s real and not just in books. That’s like, wow.”

Hensley is studying Valkyrie for an advanced independent research program, or SuperUROP, as one of only three undergraduate students in the Robot Locomotion Group in MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory. Most of her colleagues are graduate-level researchers and postdocs with extensive experience working on complex humanoids. The group is led by professor of electrical engineering and computer science Russ Tedrake, who successfully programmed Valkyrie’s predecessor (named Atlas) to open doors, turn valves, drill holes, climb stairs, and drive a car for the DARPA Robotics Challenge in 2015.

Valkyrie has 28 torque-controlled joints, four body cameras, and more than 200 individual sensors, Hensley says. The robot can walk, bend its joints, and turn a door handle. “This is one of the most advanced robots in the world. And it’s 20 feet from my desk,” she adds.

That’s largely because Valkyrie has a long way to go before it leaves for Mars. MIT is one of three institutions, including Northeastern University and the University of Edinburgh, that NASA selected to develop software enabling the robot to perform space-related tasks — open airlock hatches, attach and remove power cables, repair equipment, and retrieve samples. Oh yeah, and get to its feet when it falls down.

Hensley, who started in the lab over the summer, is intrigued by the challenge of harmonizing the movements of such a highly complex system. “I am trying to solve a very tricky problem,” she says. She’s working out how best to control Valkyrie’s elbow movements by comparing two potential approaches. One uses a main controller to gather information from the various motor systems within the arm, and then uses that data to make accurate movement decisions. The other approach is decentralized, and leaves it to each motor system to decide and act on its own.

Hensley gets animated discussing the alternatives. “Is it better to have multiple decision makers with access to different information? Or is better to have one decision maker choosing all of the motor inputs?” she asks. Hensley has already been accepted into a master’s degree program in electrical engineering at MIT. She hopes to be able to continue her work on Valkyrie.

Every day, Hensley leaves Tau Epsilon Phi, her co-ed fraternity house in the Back Bay; walks across the Massachusetts Ave. bridge to the Stata Center; and plants herself in front of two large monitors in the robotics lab. She analyzes a wealth of scientific literature and writes code for computer simulations of the equations that move the robot’s arm. Sometimes she gets up for peppermint tea, or to peer around the corner of her cubicle at Valkyrie.

One thing is certain, says Hensley. Pop culture fears that machines may soon prove superior to humans are laughable. When Valkyrie is turned on and moves, Hensley says, it often “kind of shivers and falls down. One thing you realize working in this lab is that we are really far away from the robot apocalypse,” she quips. “Sometimes robots work, and sometimes they don’t. That’s our challenge.”

tags: Artificial Intelligence, Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), Electrical Engineering & Computer Science (eecs), Mars, NASA, Research, robotics, robots, School of Engineering, Space