Robohub.org

Into the deep: Underwater machines keep an eye on climate change

The shells on crustaceans and molluscs off the Norwegian Atlantic coast are not as thick as they once were. This is because of ocean acidification, where increased carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere is absorbed by water, which raises its acidity. Researchers on the EU-funded FixO3 project, which finishes in 2017, are able to keep track of the growing CO2 and rising acidity levels in the water where these creatures live thanks to a device in the Norwegian Sea which collects data round the clock from as deep as 2 000 metres.

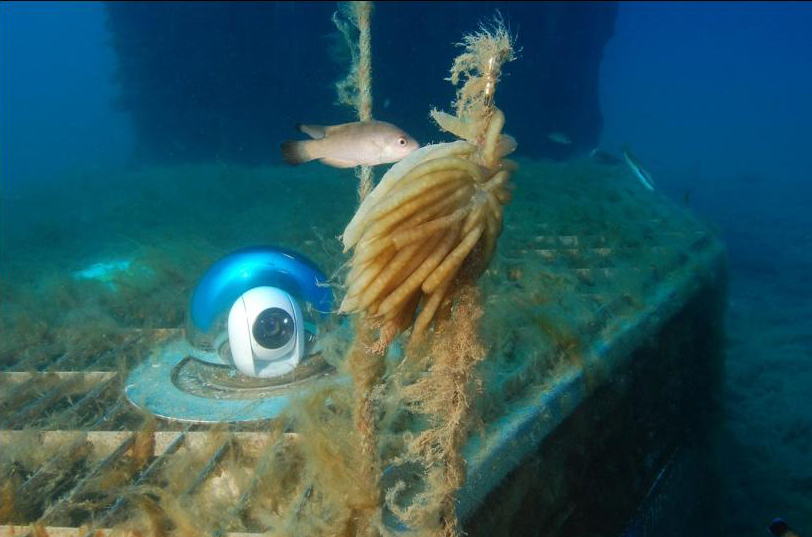

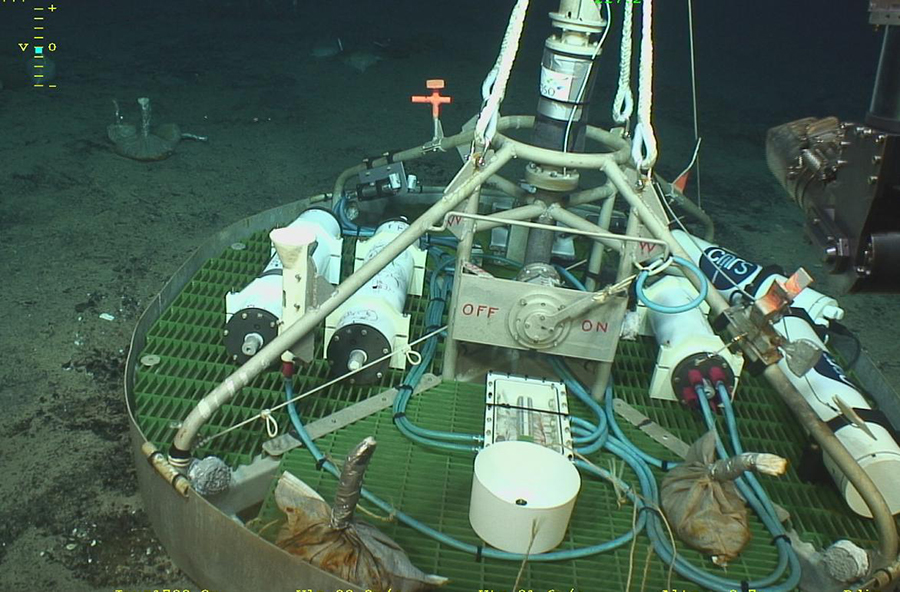

Similar tools are being set up all around Europe as part of the European Multidisciplinary Seafloor and water-column Observatory (EMSO), which is part of the EU’s centrally coordinated research infrastructures, to measure how human activities affect our oceans and worsen climate change. As well as providing food and producing oxygen through the organisms that live within them, our oceans and seas regulate our climate by transporting warm water from the equator to the poles and cold water in the other direction. Researchers are using sophisticated machines to track how our oceans are changing, from small cameras that can record high-definition videos of the ocean floor, to others that can detect earthquakes, measure temperature and pressure, and record sounds.

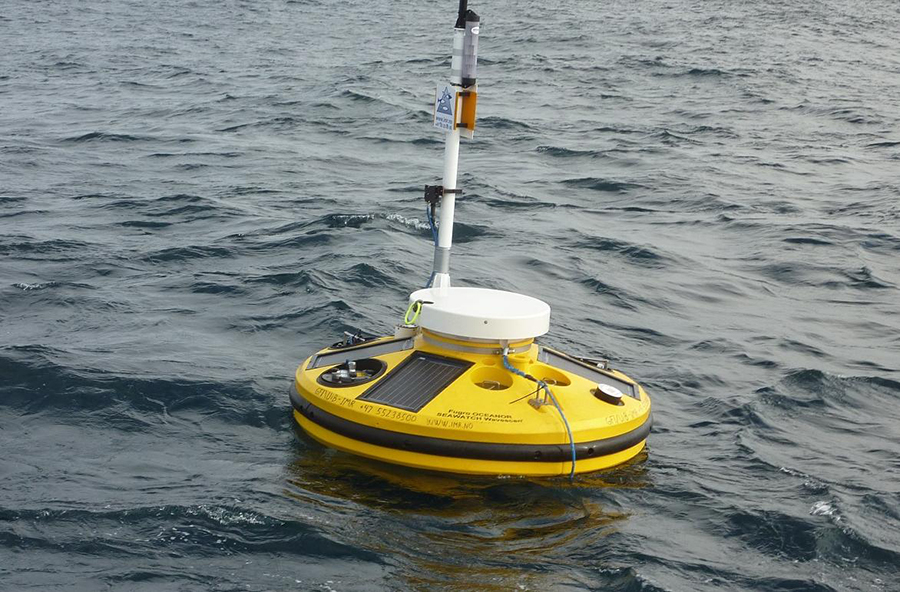

Data is transmitted from machines at the bottom of the ocean either through fibre optic cables or via buoys on the surface, which are linked to satellites. Scientists on land can then track this data, either in real time or with a delay depending on the system, and monitor pollution, climate change and even tsunamis over time. While the machines do require regular maintenance, it means that researchers are able to study the long-term health of our oceans while cutting down on costly expeditions.

Some of the findings to come out of these observatories are expected to be included in future reports by the UN’s influential Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. EMSO’s tools, such as one monitoring seismic activity and pressure on hydrothermal vents in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, will also help the EU know if it has reached its goals of improving the health of Europe’s seas by 2020, as set out in the EU’s Marine Directive. EMSO is also the European counterpart of initiatives in the US, Japan, China, Australia and other countries and will help with international collaboration in the Global Ocean Observing System, a worldwide effort to track changes in our waters.

Similar tools are being set up all around Europe as part of the European Multidisciplinary Seafloor and water-column Observatory (EMSO), which is part of the EU’s centrally coordinated research infrastructures, to measure how human activities affect our oceans and worsen climate change. As well as providing food and producing oxygen through the organisms that live within them, our oceans and seas regulate our climate by transporting warm water from the equator to the poles and cold water in the other direction. Researchers are using sophisticated machines to track how our oceans are changing, from small cameras that can record high-definition videos of the ocean floor, to others that can detect earthquakes, measure temperature and pressure, and record sounds.

This article was first published on Horizon: The EU research and innovation magazine. Click here to view the original article.

If you liked this article, you may also be interested in:

- Unmanned and underneath: Stay in the know about underwater drones

- What you need to know about underwater drones

- Autonomous underwater system for monitoring health of Venice Lagoon demos at #EXPO2015

- CoCoRo: Tracking the development of the world’s largest autonomous underwater swarm

- Ocean-going robot fleet successfully completes fish-tracking mission

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: AUV, cx-Exploration-Mining, Environment-Agriculture, Infographics, Robotics technology, ROV, Service Professional Underwater, UUV