Robohub.org

Is Viv the one assistant to rule all robots?

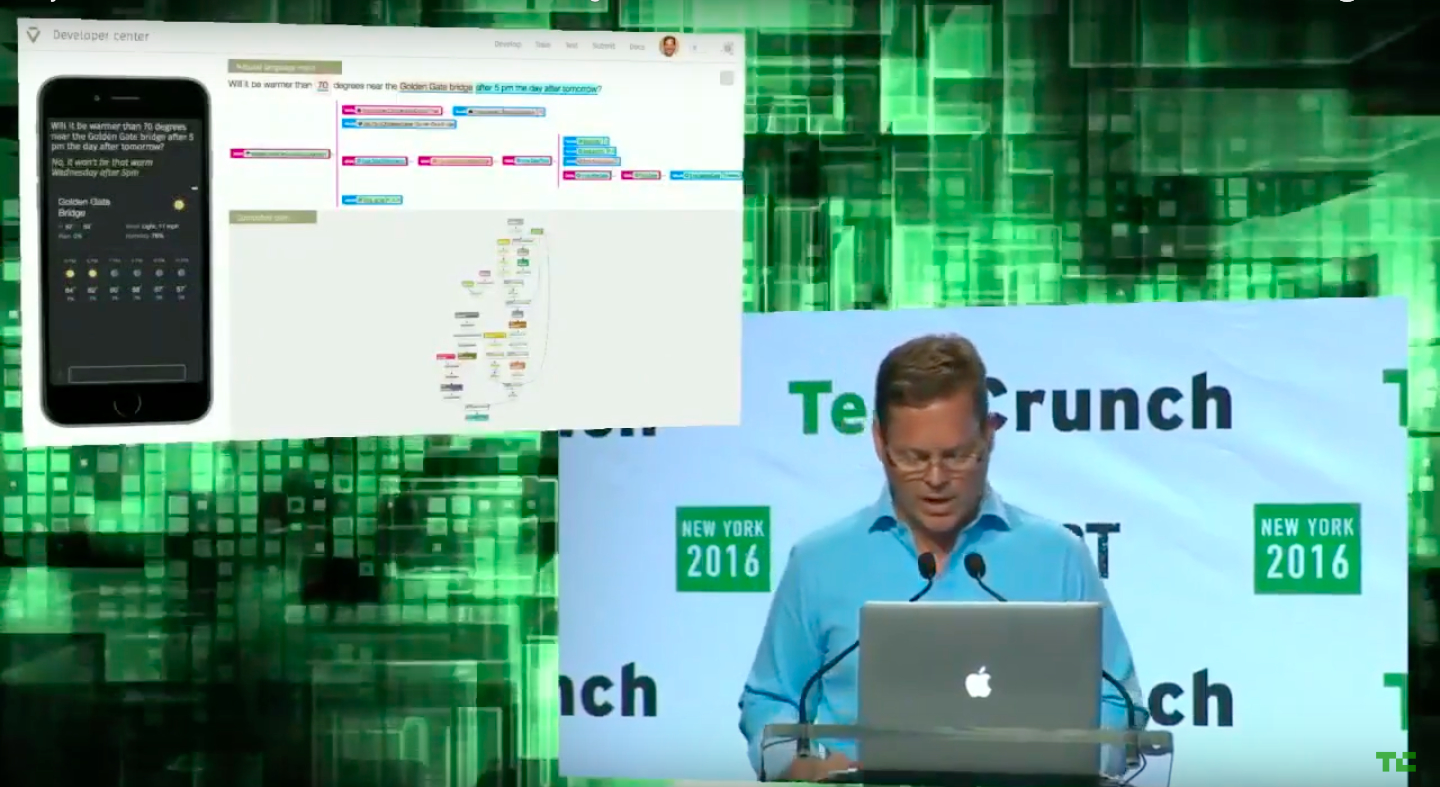

Source: YouTube/TechCrunch

Viv is an AI personal assistant launched at TechCrunch Disrupt NY. It promises to radically simplify our interface with everything. Viv is everything that Siri cofounders — Dag Kittlaus and Adam Cheyer — wanted to build with Siri, but couldn’t. Viv is a few years more advanced than Siri, but the big difference is that Steve Jobs preferred to keep Siri in a walled garden and not allow open partnerships.

Viv is a global platform that enables developers to plug into and create an intelligent, conversational interface to anything.

Cheyer and Kittlaus are focusing on creating a developer ecosystem so that Viv will be the way every device interacts with you in the future. They believe no one company can bring everything you need. But, one personal assistant can interact with all the companies and services that you need.

Viv does ‘conversational commerce’ with breathtaking speed and accuracy. I think you can forget about deep linking as the next mobile/online paradigm. Kittlaus described Viv as “the next major marketplace and channel for offering content, commerce and services.”

Viv will launch a gradually expanding developer program later in 2016. And as thousands and thousands of developers add to the Viv intelligence, the power of Viv expands. While the demo focused on showing Viv’s strengths on a phone, Viv is clearly intended to be the interface for all of our smart connected devices. And robots.

In fact, I’ll bet that my future home robot will be running on Viv.

Is there a downside?

What are could possibly go wrong in a future world full of personal assistants?

Well, while Dag Kittlaus was launching Viv at TechCrunch Disrupt NY, cofounder Adam Cheyer was in San Jose on the CHI2016 panel: “On the Future of Personal Assistants” with Phil Cohen,VoiceBox Technologies; Eric Horvitz, Microsoft Research; Rana El Kaliouby, Affectiva; and Steve Whittaker, University of California at Santa Cruz.

Firstly, the panel noted that the term ‘personal assistant’ was deceptive as we are transitioning from helpful but passive assistants, such as Siri, to active agents, such as Echo, Viv and perhaps Jibo, or other home robots in the future.

Assistants are just helpful. Agents go out into the world and perform actions.” said Phil Cohen, VoiceBox.

There are also huge potential implications in the transition from personal assistants to family assistants. Amazon’s Echo is an example of a family assistant, where the device is no longer in our hands or pockets, but sits in a room and interacts with a range of people.

How do we deal with multiple devices in various areas of our lives, ie. from car to kitchen to work to bed, and then, how do devices interact across our individual family members? Will we be creating functional or dysfunctional family agents? Navigating these issues of privacy, trust and boundaries should be at the forefront of our development.

Eric Horvitz, Microsoft, described the ‘penumbra – or bubble of data and devices’ that travels with each individual. We expect these agents to collaborate with us, but who else do our agents collaborate with in order to provide us services?

The next step is to consider how our agents can in the future interpret our emotional states. What inferences can be made, and shared, with whom? What control can be effected by these agents.

Rana El Kaliouby, Affectiva said “your fridge will understand your emotional state and help you make better decisions, if you want to change your behavior. That’s a very powerful promise.”

Cheyer was clear he doesn’t want “a plethora of different assistants… I want one assistant who can learn my preferences over time and do a better job.”

Although the intelligence might be in the cloud, the form factor of the device will give very different feel to how we interact, whether it’s a screen, TV, or a robot. And as we start to embody our assistants we change the relationship significantly.

Horvitz told an anecdote about going on holidays and turning back to bring Alexa along. Kind of like a member of the family.

Steve Whittaker, UCSC said that “we can use the metaphor of a house as an approach to designing different categories of personal assistants. A house is a collection of resources for family activities. At some level they are shared facilities for a family, but it is segmented.”

“Cortana developers are already tackling ideas of primary agency,” said Horvitz. “When I walk into a room, can I use someone else’s agent? And then is it my agent or some one else’s? And what level of shared agent? How do we develop the trust?”

“Both technically and ethically, how much access to the underlying personal information can someone else’s agent have?” added El Kaliouby.

Phil Cohen, VoiceBox questioned whether agents needed to track our beliefs, desires and intentions, or underlying emotions.

“What value or service is augmented intelligence providing in people’s lives? What tasks should a system be designed to address and for whom? Especially when a device is ambient (taking action on its own) not simply being addressed.”

Cheyer said that a useful assistant has to be transparent and allow you to change your mind about what is being shared. Whittaker said that while that might be the case for personal agents it would be very complex for family agents.

Horvitz pointed out that there are many elegant designers in the CHI community who can meet the challenge, as long as we focus on high value services that are tolerant of some uncertainty or error, so that there is a low cost of failure.

El Kaliouby added that we faced a moral obligation to give permission to some algorithms to take action. For example, some agents are showing ability to spot depression and suicidal states from things like social media posts. But what permission to they have to take action and what actions?

Whittaker pointed out that while spotting suicidal behaviors is a clear social good, generally people aren’t that good at identifying and tracking emotional states, so at what point does mood tracking create useful and actionable information?

Horvitz would like to see us address time management for people, seeing it as a huge problem that we’ve barely begun to scratch the surface of.

Cheyer sees time management or life coaching as just one of the domains that a system like Viv will start to have impact on. Although we’ll need better understanding of how we interact with AI and devices to be able to get to the next level: “Everyone is talking about the strengths of AI, but it’s not really going to solve all our problems. Where Siri was pretty dumb, Viv has light weight planning ability. Viv is able to do complex tasks with several steps which is a lot closer to the way we really ask for things. It’s not going to be doing the life planning things that Eric was asking for. But we’re working on taking actionable insights out of the unstructured data of our lives. And in the end that’s a very exciting development across all domains.”

In a room full of interactionists and ethicists, it’s no surprise that the first question to the panel was: “Is it good for society to be creating a slave class?”

This opened the door on a discussion that ranged from the ethics of ‘nagware’ up to lethal force. At which point the challenge was made for designers shift away from negativity and to create delightful solutions that would enhance and improve our lives. People-centered rather than task-centered design.

Cheyer concluded by bringing the discussion back to Viv. “Every 10 years if you look back we’ve had a new paradigm for interacting with our devices, from desktops, to web, to mobile. And each one had its problems. But I think the time is right for the assistant/agent paradigm and it’s going to be far more impactful than everyone realizes.”

Horvitz added, “The only thing I can promise for sure in the next 5 to 10 years is that we will have impacts and effects that no one has predicted.”

*note: quotes are not verbatim and have been edited for clarity.

tags: c-Events, Cortana, Siri, Viv