Robohub.org

It’s not only engineers who work in robotics

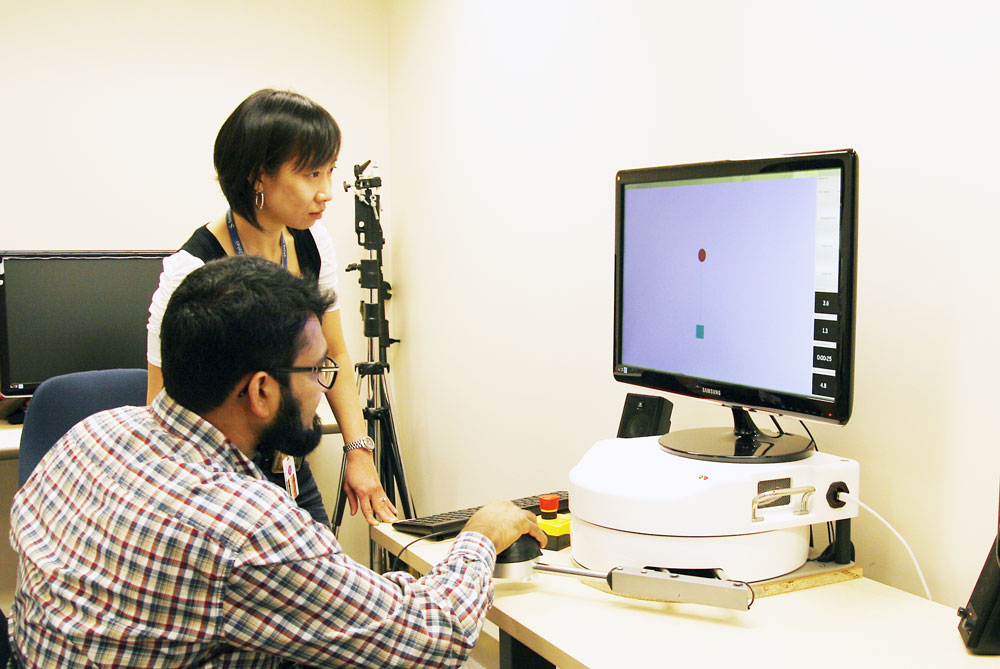

Occupational Therapist Rosalie Wang investigates how intelligent haptic robotic systems can benefit people recovering from upper limb disability due to stroke. Photo courtesy IATSL (Intelligent Assistive Technology and Systems Lab) at Toronto Rehab, University of Toronto.

Robotics has always been an interdisciplinary field – one that integrates knowledge from computer science, mechanical, electrical, controls, and other areas of engineering. But as robots move out of factories and research labs, and into our homes and workplaces, another breed of robotics expert is emerging – and an engineering or computer science degree is not necessarily part of their resume.

From occupational therapy to rehab robotics

Rosalie Wang is Assistant Professor at the Intelligent Assistive Technology and Systems Lab (IATSL), a multi-disciplinary research group at the University of Toronto made up of engineers, computer scientists, rehabilitation and medical researchers who leverage artificial intelligence and robotics to develop intelligent assistive and therapeutic devices. IATSL research runs the gamut, including obstacle avoidance and guidance systems for powered wheelchairs, fall detection solutions, intelligent haptic systems for stroke rehabilitation, personal robots to assist aging-in-place, assistive robots for people with dementia, and much more.

But Wang started her career working as an Occupational Therapist, supporting clients in long-term care. Her passion was helping seniors, and it was while working at a nursing home that she found herself tinkering with her clients’ wheelchairs. “I would come home with grease in my fingernails, having taken apart and put back together a wheelchair so that it would better fit my client’s needs.” One thing led to another, and soon she found herself doing a PhD on collision-avoidance technology for powered wheelchairs.

Translating tech into practice

Finding technical solutions to ‘people problems’ is a special skill that requires deep knowledge of both the end-user and their context, and an ability to work closely with engineers and computer scientists to understand the possibilities and limitations of the technology.

A common problem with powered wheelchairs, says Wang, is that they can be hard for someone who has physical and/or cognitive impairments to control; and because they are powered, they can also be more dangerous than manual wheelchairs, especially to someone who is already in a fragile state of health – one reason why some nursing homes have banned the use of powered wheelchairs altogether. And then there are the ethical aspects: “It’s hard to take a powered wheelchair away from someone once you’ve given them one. We want to enable mobility, and we want to keep people safe, and we want to do it in a way that respects the client,” says Wang.

Wang also points out that simply having technology that works under certain conditions doesn’t mean it will be taken up in practice; many contextual factors that lie outside the technology itself can get in the way. For example, most fall detection monitoring services tend to use a subscription-based business model, similar to home monitoring. But Wang has found that many clients prefer to have their personal care monitoring service trigger warning calls to a family member rather than a call center – even though this solution is less likely to be taken up by industry partners. “As you’re designing the system, you have to look at the whole picture. Clients feel there is a stigma attached to disrupting a call centre.”

Developing technology into systems and products that can actually be deployed into real world scenarios is a challenge, and it’s important to understand clients’ personal preferences and their physical and cognitive abilities, as well as contextual factors, such as nursing home architecture, routines and regulations, family and caregiver needs, ethics and more. This is why a critical part of the research at IATSL is also to develop frameworks, guidelines and methodologies for applying intelligent assistive technologies in nursing homes and at home.

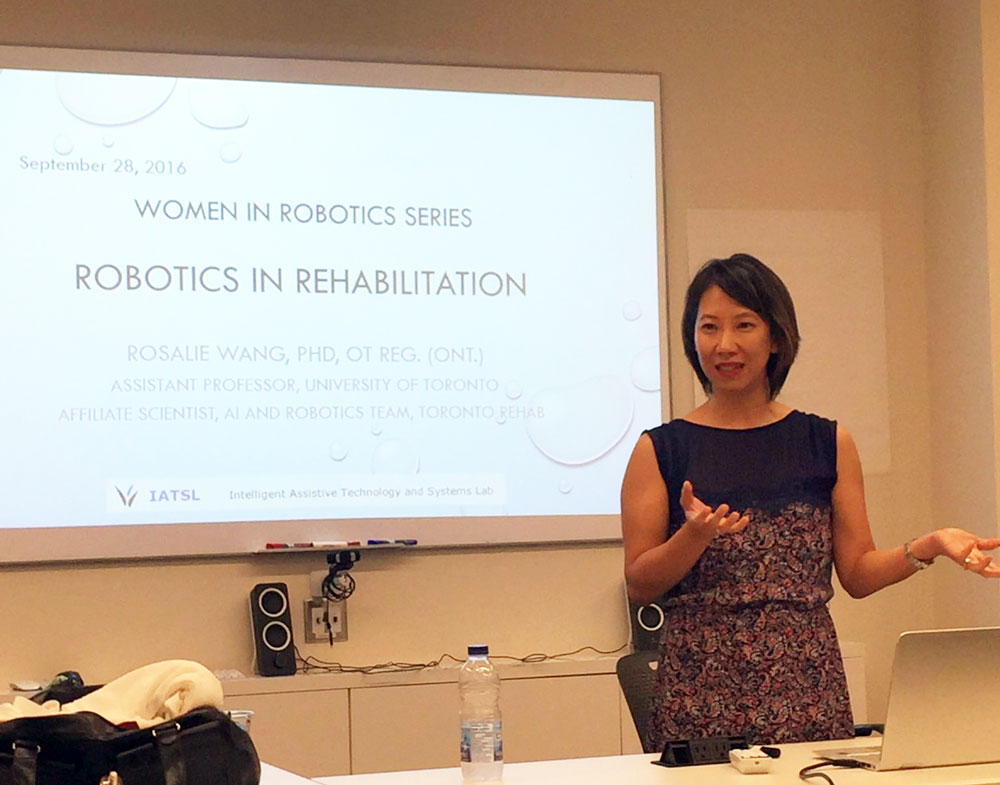

Rosalie Wang speaks about her career path from Occupational Therapist to rehab robotics researcher at the Women in Robotics lecture series, hosted by Get Your Bot On and Women Engineers TO in Toronto, Canada. Photo via Nicole Proulx.

For Wang, the benefits of being an Occupational Therapist in the field of robotics and AI cut both ways: she can bring a user-centered perspective to designing the technology, but “Robotics and AI can also help to augment the work of the Occupational Therapist and advance the field as a whole,” she says. Wang’s research also includes clinically evaluating robots for upper limb stroke rehabilitation and assistive robots to help older adults with dementia. Her latest paper, just published last month, examines how older adults with Alzheimer’s and their caregivers feel about using robots to help them complete tasks at home, and is one of the few studies to give an in-depth perspective on the issue.

From an Occupational Therapist’s perspective, one of the key benefits of employing robotics and AI is that it can yield data for evidence-based therapy. “It used to be that we could only measure therapy results with very coarse snapshots … a client either could complete a task or they could not complete it. This kind of feedback is potentially very demoralizing to the client, and makes it harder for the therapist to perceive and record small changes in progress… Now we can collect continuous data, which lets us design more refined therapies, and gives clients a better sense of progress. A therapy robot can give you continuous clinical data, even when you can’t perceive it.”

When asked if she ever imagined she would be working in robotics one day, Wang gave a resounding answer: “No.” And she is reluctant to describe herself as a roboticist. Still, given the wide range of projects being undertaken at the Intelligent Assistive Technology and Systems Lab, it’s clear that it takes an interdisciplinary team with all kinds of expertise to translate robotics and AI into practical healthcare solutions.

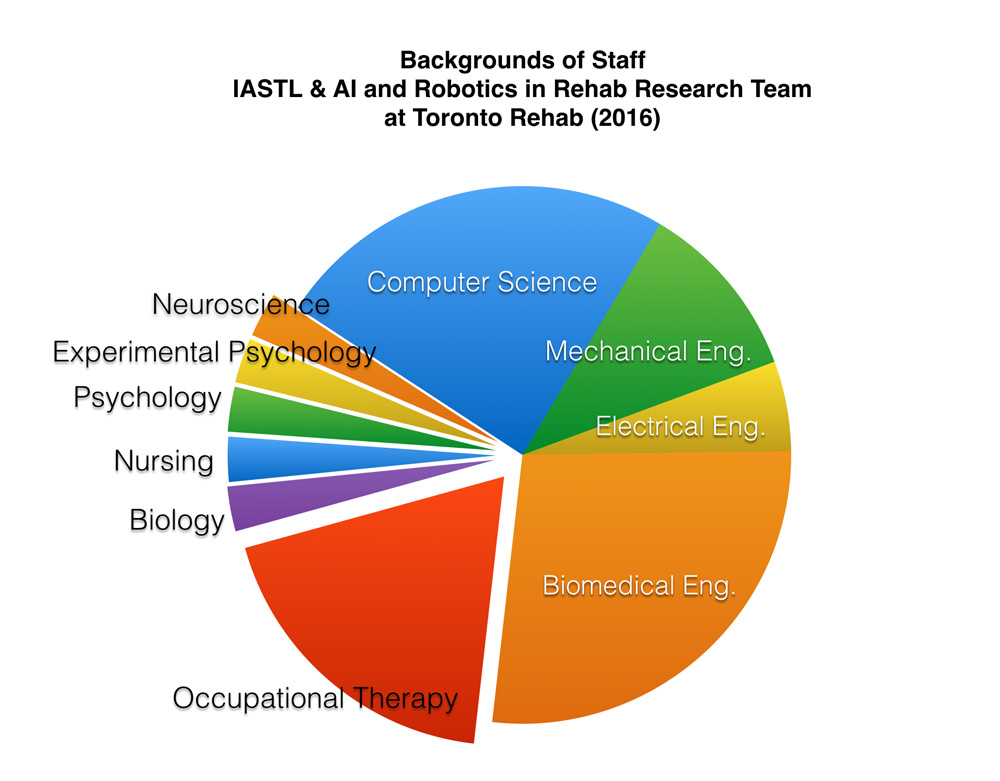

Team members at IATSL have backgrounds that include occupational therapy, neuroscience, industrial design, biology, clinical psychology, experimental psychology, rehabilitation science, and nursing.

tags: c-Health-Medicine, Canada, cx-Research-Innovation, University of Toronto