Robohub.org

A brief history of robotic force torque sensors

Force torque sensors are now ubiquitous in robotics, but where did they come from? What series of inventions and discoveries happened for robot force sensors to arrive where they are today? It turns out, this sensor was developed thanks to the hard work of many scientists, inventors and researchers.

Let’s take a look at the history of the force torque sensor.

Early history – scientists under pressure

The first step toward robot force sensors was taken by the classical scientists of antiquity. However, they weren’t interested in force, but rather pressure. We now know that pressure is defined by “force over area” but in the beginning, the only “area” people were interested in was a field of dry crops that needed to be watered.

1594: Galileo is confounded

It all started because Galileo Galilei designed and patented a machine for irrigating crops. It used a syringe-based suction pump to pull water out of a river. Unfortunately, there was a problem with the machine – the pump could never pull the water above 10m. Galileo couldn’t find the explanation why. The problem puzzled him, and other scientists, for years.

1644 – 1661: Filling the vacuum

Finally, the puzzling question of pressure was solved during a succession of discoveries in the 17th century. In 1644, Evangelista Torricelli explained Galileo’s problem being caused by the weight of the water and declared the existence of the empty vacuum, which annoyed supporters of the omni-present god. Two years later, Blaise Pascal walked up a mountain to prove pressure is the force of air. Then in 1656 Offo von Guerke developed a new vacuum pump and tested the vacuum by trying (and failing) to pull it apart with eight horses. Finally in 1661, Robert Boyle derived the relationship between pressure and volume of air which sets the stage for the first force sensor.

in the 17th century. In 1644, Evangelista Torricelli explained Galileo’s problem being caused by the weight of the water and declared the existence of the empty vacuum, which annoyed supporters of the omni-present god. Two years later, Blaise Pascal walked up a mountain to prove pressure is the force of air. Then in 1656 Offo von Guerke developed a new vacuum pump and tested the vacuum by trying (and failing) to pull it apart with eight horses. Finally in 1661, Robert Boyle derived the relationship between pressure and volume of air which sets the stage for the first force sensor.

All in all, it was a busy 17 years! It gave us a fundamental understanding of the relationship between pressure and force. However, after such a busy period, activity died down for the development of force sensing. Nothing happened for almost 200 years.

Late antiquity – A sense of change

Old aneroid barometer. Image credit: David R. Ingham via Wikipedia

1843 – 1849: The first force sensor

In 1843, the first force sensor was developed – the aneroid barometer. This was followed by the Bourdon tube in 1849. These sensors used the principles discovered 200 years earlier to measure the atmospheric pressure. A fixed volume of air contracts or expands as the atmospheric pressure changes, moving the needle on the dial. Using the same principle, MEMS barometers have been developed into cheap robot force sensors in the form of the TakkTile sensor from Harvard Biorobotics Laboratory.

1843 – 1856: The Wheatstone Bridge – born 100 years too early

At exactly the same time a key theory was developed that would become a vital part of modern force sensors. Sir Charles Wheatstone designed an electric circuit that could precisely measure resistance of an unknown resistor (which would eventually be replaced by a strain gauge). In 1856, Lord Kelvin presented a report on the relationship between mechanical strain and electrical resistance.

Unfortunately these developments would have to wait for over a century to actually be applied to force sensors. Nothing much happened for 80 years. The theories of Sir Wheatstone and Lord Kelvin sat around in textbooks, just waiting for modern electronics to catch up with them.

The Middle Ages – starting to feel the strain

1936: The birth of the strain gauge

The strain gauge was born into existence by an aerospace engineer, Charles M. Kearns. He just got hired at the Hamilton Standard Propeller Company and was assigned to solve the problem of inflight propeller failures. Existing methods to detect mechanical strain used carbon-based paints, which were painted onto propeller blades. As a keen amateur radio enthusiast, Kearns had an idea to grind down a carbon resistor, stick it to the blade and measure its changing resistance to calculate how much the propeller had bent. Within four years, in-flight propeller failures were eliminated as a problem and the strain gauge was born.

1938: The strain gauge grows up

By the end of the 1930s, the race was on to improve the strain gauge force sensor. Bonded wire strain gauges were developed by two different researchers simultaneously – E.E. Simmons at Caltech and Arthur Ruge at MIT. Simmons was faster to apply for a patent. Wire strain gauges became the new standard.

1952 – 1953: Foiled again

The development of the force sensor had only begun. In early 1952, an engineer called Peter Jackson grew frustrated by various flaws made the wire strain gauges useless for his helicopter application. He decided they were a waste of time and invented the foil strain gauge in 1953.

1967 – 1969: Silicon strain gauges

With the rise of semiconductor fabrication, it was inevitable that strain gauges would eventually be made out of silicon. By 1967, Zias and Egan of the Honeywell Research Center had patented the technology. In 1969, Hans W. Keller patented the first batch-fabrication process. By the 1970s, silicon strain gauges were ready for robotics to enter the scene.

The early modern period – robots arrive!

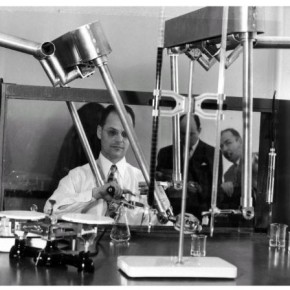

1949 – 1951: Teleoperation kicks it all off

Before the first industrial robots had even been dreamt up by George Devol, Raymond Goertz at the Argonne National Laboratory was integrating force feedback into robotic teleoperations, which he then used to handle radioactive materials. His first teleoperations were purely mechanical linkages, that gave them inherent force feedback. In 1951, he patented an electrical manipulator. This was a major milestone for teleoperation and haptic research and has been the forefront of force control research ever since.

Before the first industrial robots had even been dreamt up by George Devol, Raymond Goertz at the Argonne National Laboratory was integrating force feedback into robotic teleoperations, which he then used to handle radioactive materials. His first teleoperations were purely mechanical linkages, that gave them inherent force feedback. In 1951, he patented an electrical manipulator. This was a major milestone for teleoperation and haptic research and has been the forefront of force control research ever since.

1961: Industrial robots arrive

The first industrial robot, Unimate, came on the scene in 1961. It did not have force control. Neither did most industrial robots, until quite recently. They used motion control techniques (e.g. position or velocity controllers) which meant they had to follow strictly defined paths and could not monitor the force applied by the robot on the task.

Although force control wouldn’t reach factory robots for some time, researchers started to integrate force sensors into their robots.

Modern day – The force awakens

1970s or thereabouts: The 6-Axis force torque sensor arrives

In the 1970s, the 6-axis force torque sensor was invented. Unlike the previous developments is not clear who first invented it. Patents were filed around 1980 for multi-axis load cells and there were research papers around the same time. Strain gauge based mechanical load cells had been around for a while; it is likely the first 6-axis force torque sensor was the result of steady research conducted by several research groups, like most modern robotic developments.

1970s – 21st Century: Research abounds

As early as 1973, force control was integrated into robotic manipulators. At some point, somebody stuck a 6-axis force torque sensor onto a robot. It’s not clear who did this first. From the late 1970s right up to present day and beyond, force control research has increased in strength.

2016 and beyond: What’s next in the world of force sensors

Now, there are so many new force sensing technologies it’s hard to keep up. The 6-axis force torque sensor has only started to take off in industry, but in the world of researchers there are new sensing technologies coming out every day. After such a long history, the force sensor has definitely become an integral part of robotics.![]()

tags: c-Education-DIY, robotiq