Robohub.org

Shared autonomy via deep reinforcement learning

By Siddharth Reddy

Imagine a drone pilot remotely flying a quadrotor, using an onboard camera to navigate and land. Unfamiliar flight dynamics, terrain, and network latency can make this system challenging for a human to control. One approach to this problem is to train an autonomous agent to perform tasks like patrolling and mapping without human intervention. This strategy works well when the task is clearly specified and the agent can observe all the information it needs to succeed. Unfortunately, many real-world applications that involve human users do not satisfy these conditions: the user’s intent is often private information that the agent cannot directly access, and the task may be too complicated for the user to precisely define. For example, the pilot may want to track a set of moving objects (e.g., a herd of animals) and change object priorities on the fly (e.g., focus on individuals who unexpectedly appear injured). Shared autonomy addresses this problem by combining user input with automated assistance; in other words, augmenting human control instead of replacing it.

A blind, autonomous pilot (left), suboptimal human pilot (center), and combined human-machine team (right) play the Lunar Lander game.

Background

The idea of combining human and machine intelligence in a shared-control system goes back to the early days of Ray Goertz’s master-slave manipulator in 1949, Ralph Mosher’s Hardiman exoskeleton in 1969, and Marvin Minsky’s call for telepresence in 1980. After decades of research in robotics, human-computer interaction, and artificial intelligence, interfacing between a human operator and a remote-controlled robot remains a challenge. According to a review of the 2015 DARPA Robotics Challenge, “the most cost effective research area to improve robot performance is Human-Robot Interaction….The biggest enemy of robot stability and performance in the DRC was operator errors. Developing ways to avoid and survive operator errors is crucial for real-world robotics. Human operators make mistakes under pressure, especially without extensive training and practice in realistic conditions.”

|

|

|

Master-slave robotic manipulator (Goertz, 1949) |

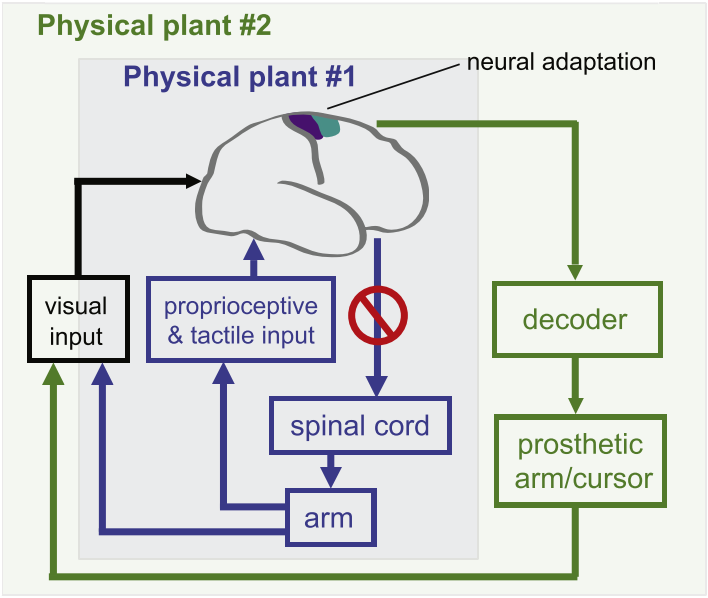

Brain-computer interface for neural prosthetics (Shenoy & Carmena, 2014) |

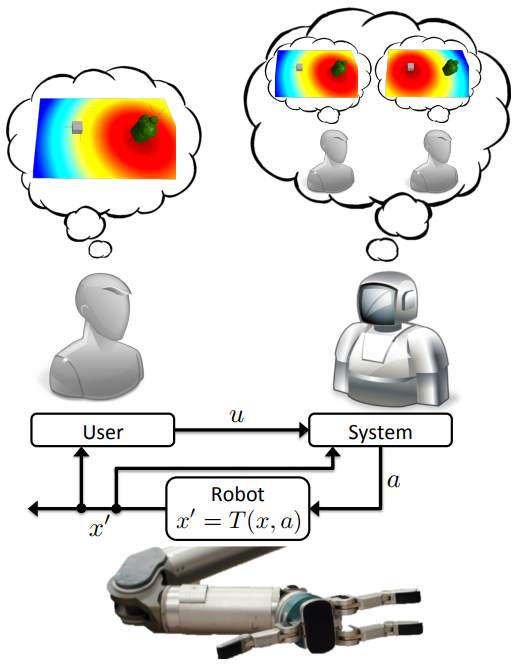

Formalism for model-based shared autonomy (Javdani et al., 2015) |

One research thrust in shared autonomy approaches this problem by inferring the user’s goals and autonomously acting to achieve them. Chapter 5 of Shervin Javdani’s Ph.D. thesis contains an excellent review of the literature. Such methods have made progress toward better driver assist, brain-computer interfaces for prosthetic limbs, and assistive teleoperation, but tend to require prior knowledge about the world; specifically, (1) a dynamics model that predicts the consequences of taking a given action in a given state of the environment, (2) the set of possible goals for the user, and (3) an observation model that describes the user’s behavior given their goal. Model-based shared autonomy algorithms are well-suited to domains in which this knowledge can be directly hard-coded or learned, but are challenged by unstructured environments with ill-defined goals and unpredictable user behavior. We approached this problem from a different angle, using deep reinforcement learning to implement model-free shared autonomy.

Deep reinforcement learning uses neural network function approximation to tackle the curse of dimensionality in high-dimensional, continuous state and action spaces, and has recently achieved remarkable success in training autonomous agents from scratch to play video games, defeat human world champions at Go, and control robots. We have taken preliminary steps toward answering the following question: can deep reinforcement learning be useful for building flexible and practical assistive systems?

Model-Free RL with a Human in the Loop

To enable shared-control teleoperation with minimal prior assumptions, we devised a model-free deep reinforcement learning algorithm for shared autonomy. The key idea is to learn an end-to-end mapping from environmental observation and user input to agent action, with task reward as the only form of supervision. From the agent’s perspective, the user acts like a prior policy that can be fine-tuned, and an additional sensor generating observations from which the agent can implicitly decode the user’s private information. From the user’s perspective, the agent behaves like an adaptive interface that learns a personalized mapping from user commands to actions that maximizes task reward.

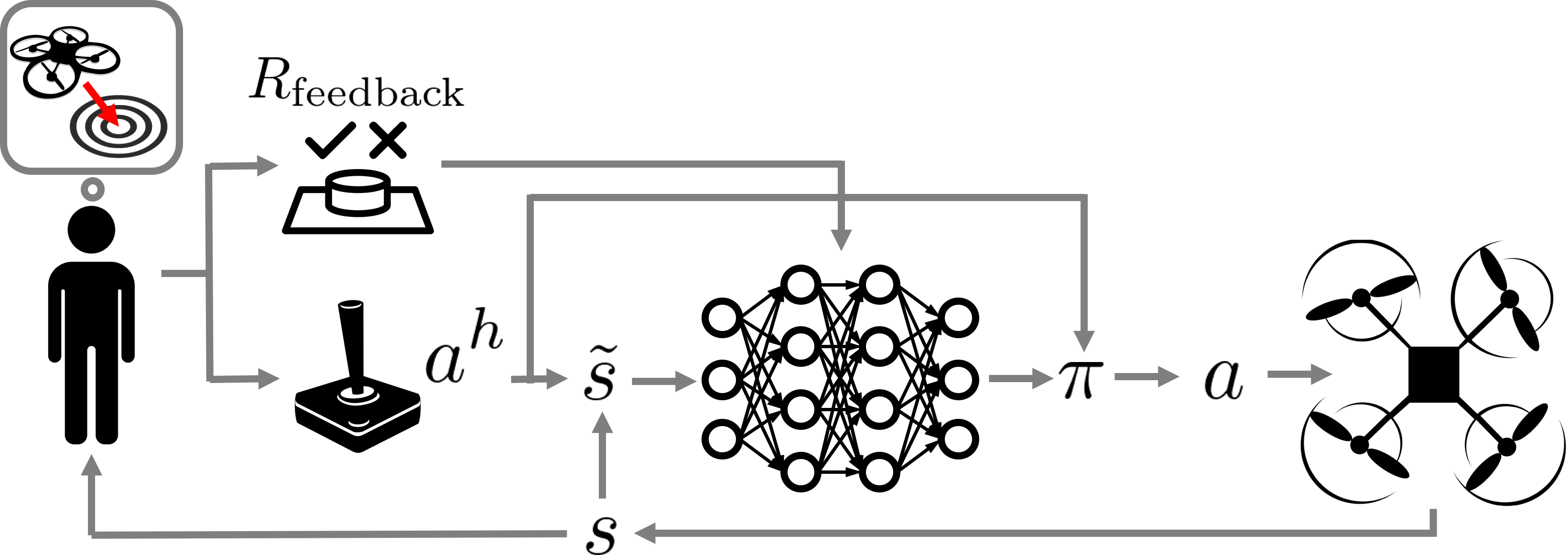

Fig. 1: An overview of our human-in-the-loop deep Q-learning algorithm for model-free shared autonomy

One of the core challenges in this work was adapting standard deep RL techniques to leverage control input from a human without significantly interfering with the user’s feedback control loop or tiring them with a long training period. To address these issues, we used deep Q-learning to learn an approximate state-action value function that computes the expected future return of an action given the current environmental observation and the user’s input. Equipped with this value function, the assistive agent executes the closest high-value action to the user’s control input. The reward function for the agent is a combination of known terms computed for every state, and a terminal reward provided by the user upon succeeding or failing at the task. See Fig. 1 for a high-level schematic of this process.

Learning to Assist

Prior work has formalized shared autonomy as a partially-observable Markov decision process (POMDP) in which the user’s goal is initially unknown to the agent and must be inferred in order to complete the task. Existing methods tend to assume the following components of the POMDP are known ex-ante: (1) the dynamics of the environment, or the state transition distribution $T$; (2) the set of possible goals for the user, or the goal space $\mathcal{G}$; and (3) the user’s control policy given their goal, or the user model $\pi_h$. In our work, we relaxed these three standard assumptions. We introduced a model-free deep reinforcement learning method that is capable of providing assistance without access to this knowledge, but can also take advantage of a user model and goal space when they are known.

In our problem formulation, the transition distribution $T$, the user’s policy $\pi_h$, and the goal space $\mathcal{G}$ are no longer all necessarily known to the agent. The reward function, which depends on the user’s private information, is

$$

R(s, a, s’) = \underbrace{R_{\text{general}}(s, a, s’)}_\text{known} + \underbrace{R_{\text{feedback}}(s, a, s’)}_\text{unknown, but observed}.

$$

This decomposition follows a structure typically present in shared autonomy: there are some terms in the reward that are known, such as the need to avoid collisions. We capture these in $R_{\text{general}}$. $R_{\text{feedback}}$ is user-generated feedback that depends on their private information. We do not know this function. We merely assume the agent is informed when the user provides feedback (e.g., by pressing a button). In practice, the user might simply indicate once per trial whether the agent succeeded or not.

Incorporating User Input

Our method jointly embeds the agent’s observation of the environment $s_t$ with the information from the user $u_t$ by simply concatenating them. Formally,

$$

\tilde{s}_t = \left[ \begin{array}{c} s_t \\ u_t \end{array} \right].

$$

The particular form of $u_t$ depends on the available information. When we do not know the set of possible goals $\mathcal{G}$ or the user’s policy given their goal $\pi_h$, as is the case for most of our experiments, we set $u_t$ to the user’s action $a^h_t$. When we know the goal space $\mathcal{G}$, we set $u_t$ to the inferred goal $\hat{g}_t$. In particular, for problems with known goal spaces and user models, we found that using maximum entropy inverse reinforcement learning to infer $\hat{g}_t$ led to improved performance. For problems with known goal spaces but unknown user models, we found that under certain conditions we could improve performance by training an LSTM recurrent neural network to predict $\hat{g}_t$ given the sequence of user inputs using a training set of rollouts produced by the unassisted user.

Q-Learning with User Control

Model-free reinforcement learning with a human in the loop poses two challenges: (1) maintaining informative user input and (2) minimizing the number of interactions with the environment. If the user input is a suggested control, consistently ignoring the suggestion and taking a different action can degrade the quality of user input, since humans rely on feedback from their actions to perform real-time control tasks. Popular on-policy algorithms like TRPO are difficult to deploy in this setting since they give no guarantees on how often the user’s input is ignored. They also tend to require a large number of interactions with the environment, which is impractical for human users. Motivated by these two criteria, we turned to deep Q-learning.

Q-learning is an off-policy algorithm, enabling us to address (1) by modifying the behavior policy used to select actions given their expected returns and the user’s input. Drawing inspiration from the minimal intervention principle embodied in recent work on parallel autonomy and outer-loop stabilization, we execute a feasible action closest to the user’s suggestion, where an action is feasible if it isn’t that much worse than the optimal action. Formally,

$$

\pi_{\alpha}(a \mid \tilde{s}, a^h) = \delta\left(a = \mathop{\arg\max}\limits_{\{a : Q'(\tilde{s}, a) \geq (1 – \alpha) Q'(\tilde{s}, a^\ast)\}} f(a, a^h)\right),

$$

where $f$ is an action-similarity function and $Q'(\tilde{s}, a) = Q(\tilde{s}, a) – \min_{a’ \in \mathcal{A}} Q(\tilde{s}, a’)$ maintains a sane comparison for negative Q values. The constant $\alpha \in [0, 1]$ is a hyperparameter that controls the tolerance of the system to suboptimal human suggestions, or equivalently, the amount of assistance.

Mindful of (2), we note that off-policy Q-learning tends to be more sample-efficient than policy gradient and Monte Carlo value-based methods. The structure of our behavior policy also speeds up learning when the user is approximately optimal: for appropriately large $\alpha$, the agent learns to fine-tune the user’s policy instead of learning to perform the task from scratch. In practice, this means that during the early stages of learning, the combined human-machine team performs at least as well as the unassisted human instead of performing at the level of a random policy.

User Studies

We applied our method to two real-time assistive control problems: the Lunar Lander game and a quadrotor landing task. Both tasks involved controlling motion using a discrete action space and low-dimensional state observations that include position, orientation, and velocity information. In both tasks, the human pilot had private information that was necessary to complete the task, but wasn’t capable of succeeding on their own.

The Lunar Lander Game

The objective of the game was to land the vehicle between the flags without crashing or flying out of bounds using two lateral thrusters and a main engine. The assistive copilot could observe the lander’s position, orientation, and velocity, but not the position of the flags.

|

|

Human Pilot (Solo): The human pilot can’t stabilize and keeps crashing. |

Human Pilot + RL Copilot: The copilot improves stability while giving the pilot enough freedom to land between the flags. |

Humans rarely beat the Lunar Lander game on their own, but with a copilot they did much better.

Fig. 2a: Success and crash rates averaged over 30 episodes.

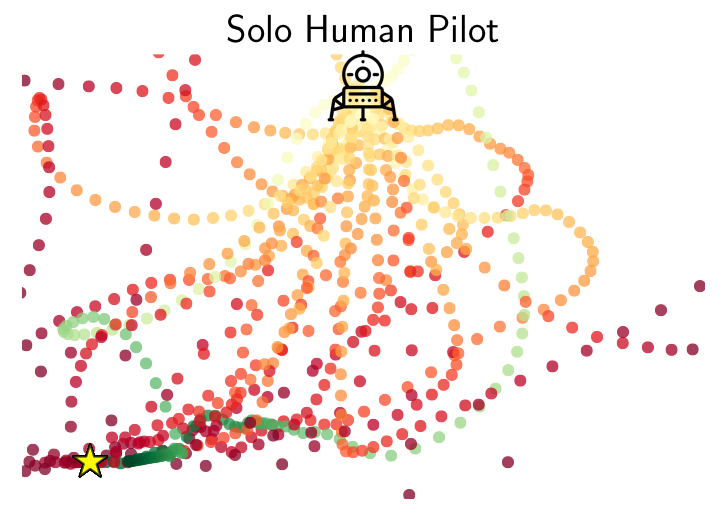

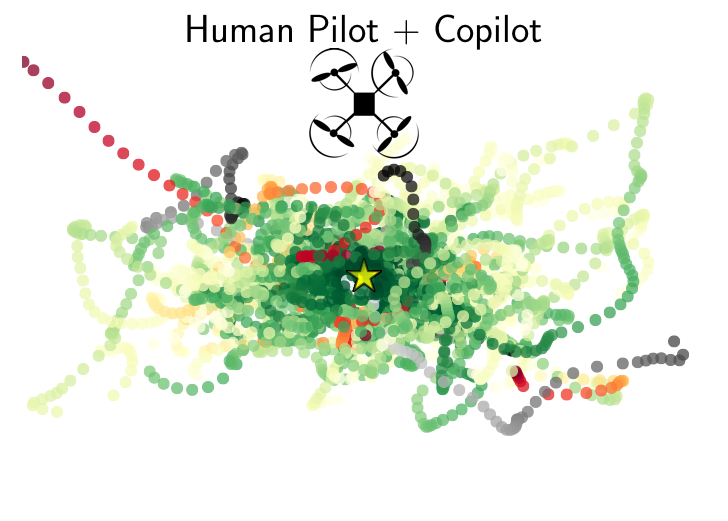

Fig. 2b-c: Trajectories followed by human pilots with and without a copilot on Lunar Lander. Red trajectories end in a crash or out of bounds, green in success, and gray in neither. The landing pad is marked by a star. For the sake of illustration, we only show data for a landing site on the left boundary.

In simulation experiments with synthetic pilot models (not shown here), we also observed a significant benefit to explicitly inferring the goal (i.e., the location of the landing pad) instead of simply adding the user’s raw control input to the agent’s observations, suggesting that goal spaces and user models can and should be taken advantage of when they are available.

One of the drawbacks of analyzing Lunar Lander is that the game interface

and physics do not reflect the complexity and unpredictability of a real-world robotic shared autonomy task.

To evaluate our method in a more realistic environment, we formulated a task for a human pilot flying a real quadrotor.

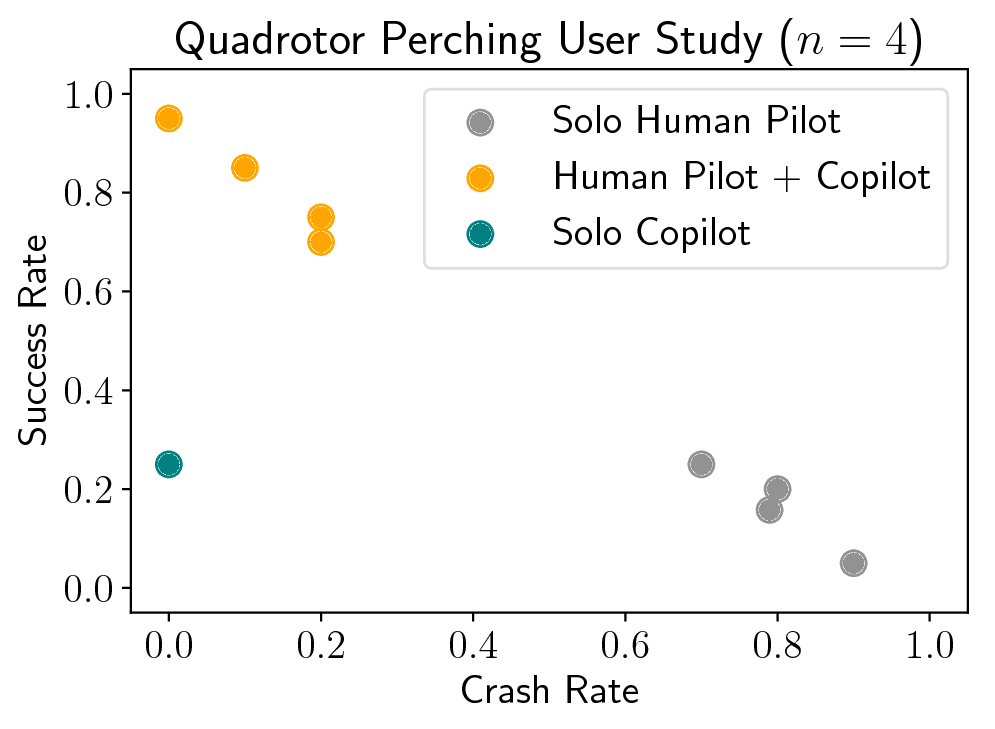

Quadrotor Landing Task

The objective of the task was to land a Parrot AR-Drone 2 on a small, square landing pad at some distance from its initial take-off position, such that the drone’s first-person camera was pointed at a random object in the environment (e.g., a red chair), without flying out of bounds or running out of time. The pilot used a keyboard to control velocity, and was blocked from getting a third-person view of the drone so that they had to rely on the drone’s first-person camera feed to navigate and land. The assistive copilot observed position, orientation, and velocity, but did not know which object the pilot wanted to look at.

|

|

|

Human Pilot (Solo): The pilot’s display only showed the drone’s first-person view, so pointing the camera was easy but finding the landing pad was hard. |

Human Pilot + RL Copilot: The copilot didn’t know where the pilot wanted to point the camera, but it knew where the landing pad was. Together, the pilot and copilot succeeded at the task. |

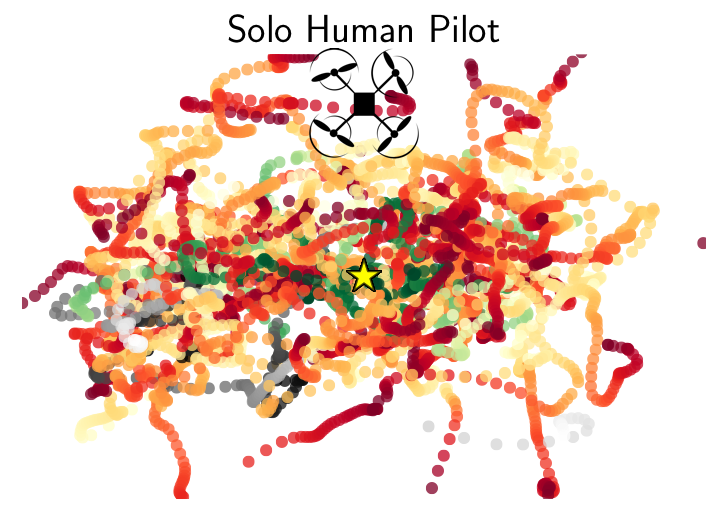

Humans found it challenging to simultaneously point the camera at the desired scene and navigate to the precise location of a feasible landing pad under time constraints.

The assistive copilot had little trouble navigating to and landing on the landing pad, but did not know where to point the camera because it did not know what the human wanted to observe after landing. Together, the human could focus on pointing the camera and the copilot could focus on landing precisely on the landing pad.

Fig. 3a: Success and crash rates averaged over 20 episodes.

Fig. 3b-c: A bird’s-eye view of trajectories followed by human pilots with and without a copilot on the quadrotor landing task. Red trajectories end in a crash or out of bounds, green in success, and gray in neither. The landing pad is marked by a star.

Our results showed that combined pilot-copilot teams significantly outperform individual pilots and copilots.

What’s Next?

Our method has a major weakness: model-free deep reinforcement learning typically requires lots of training data, which can be burdensome for human users operating physical robots. We mitigated this issue in our experiments by pretraining the copilot in simulation without a human pilot in the loop. Unfortunately, this is not always feasible for real-world applications due to the difficulty of building high-fidelity simulators and designing rich user-agnostic reward functions $R_{\text{general}}$. We are currently exploring different approaches to this problem.

If you want to learn more, check out our pre-print on arXiv: Siddharth Reddy, Anca Dragan, Sergey Levine, Shared Autonomy via Deep Reinforcement Learning, arXiv, 2018.

The paper will appear at Robotics: Science and Systems 2018 from June 26-30. To encourage replication and extensions, we have released our code. Additional videos are available through the project website.

This article was initially published on the BAIR blog, and appears here with the authors’ permission.

tags: herotagrc