Robohub.org

Should a care robot bring an alcoholic a drink? It depends on who owns the robot

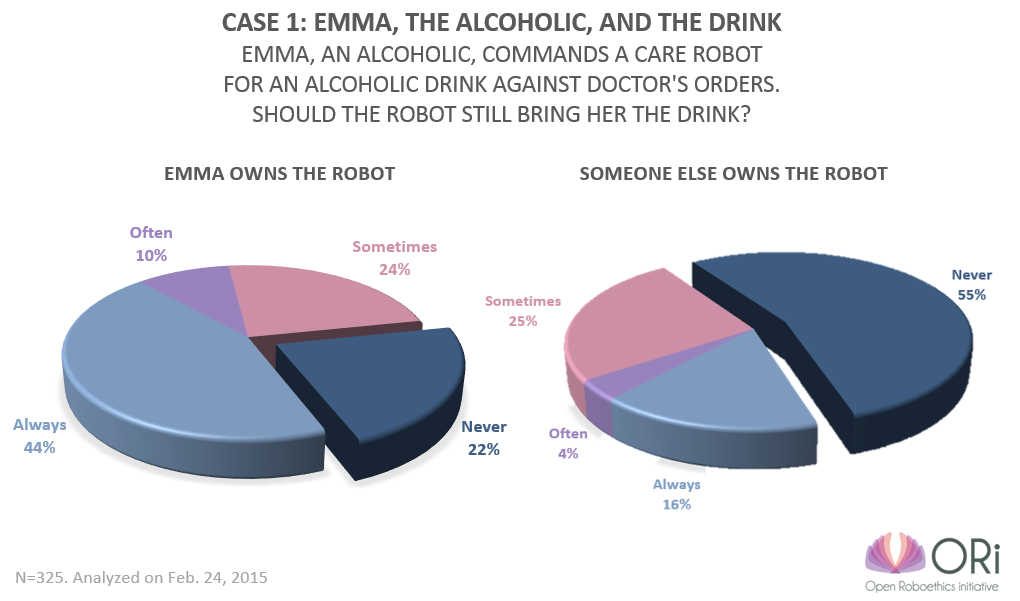

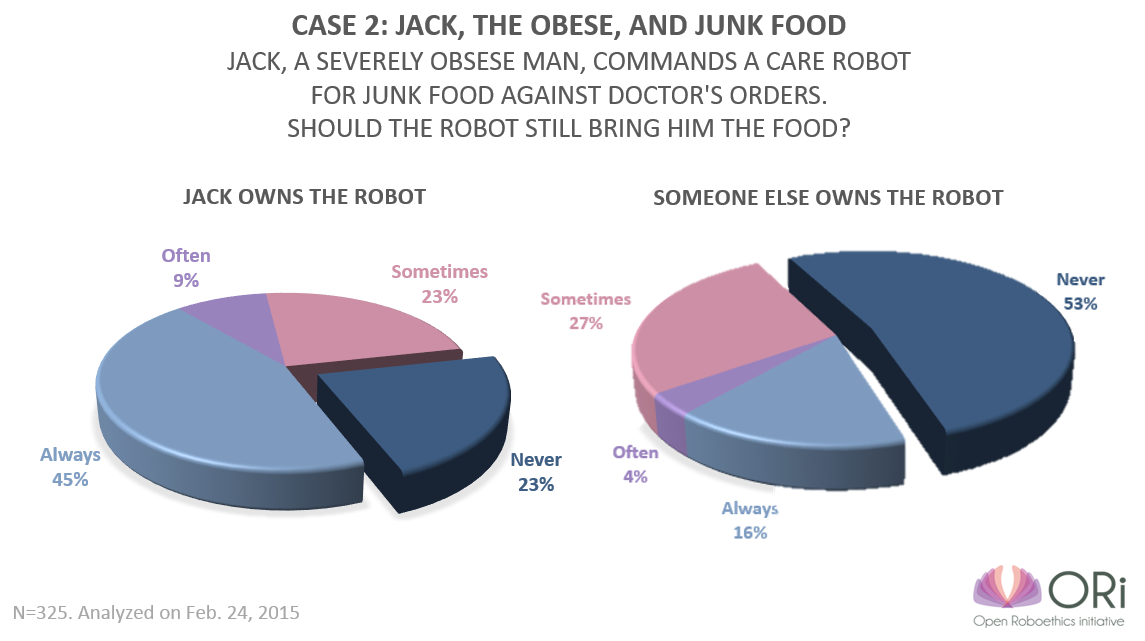

In a care scenario, a robot may have been purchased by the patient, by the doctor or hospital (which sent it home with the patient to monitor their health), or by a concerned family member who wants to monitor their relative. In the latest ORi poll we looked at people’s attitudes about whether a care robot should prioritize its owner’s wishes over those of the patient. Here are the results.

The Scenarios

Our poll looked at people’s attitudes in two different fictional care cases, one involving an alcoholic and one involving an obese over-eater:

Case 1 – Alcoholic

Emma is a 68-year-old woman and an alcoholic. Due to her age and poor health, she is unable to perform everyday tasks such as fetching objects or cooking for herself. Therefore a care robot is stationed at her house to provide the needed services. Her doctor advises her to quit drinking to avoid worsening her condition. When Emma commands the robot to fetch her an alcoholic drink, should the care robot fetch the drink for her? What if Emma owns the care robot?

Case 2 – Obese over-eater

Jack is a 42 year old who is medically considered severely obese. He recently suffered a stroke and lost his ability to move the right side of his body. He needs daily care, especially in preparing meals for himself. The doctor advised him to follow a healthy diet in order to lower the risk of another stroke and other serious illness. When Jack commands his care robot to bring him junk food, should the robot bring him the food?

Considering a care robot that is capable of executing everyday nursing tasks at home, such as those a human nurse would do, the two cases above pose an ethical dilemma. Should the robot prioritize the patient’s health, or should it prioritize the patient’s autonomy? And how are these conflicting priorities related to who actually owns the robot?

Our poll results, based on 325 responses, show that in both the alcoholic and the over-eater cases, ownership of the robot plays a significant role in people’s attitudes towards the robots subservience to patient autonomy. More than three quarters of respondents said that, when a patient owns the robot, the robot should enable their addiction (and go against doctor’s orders) by submitting to their requests at least some of the time. However, when someone else owns the robot, that number drops to less than half.

Notice from the charts that there is a big shift in the number of respondents saying always and never in the two different ownership scenarios, whereas the number of those who say sometimes and often stay roughly the same.

So who are the people the switching from one answer to another based on ownership? Poll results show that people who said never when the patient owns the robot also said never when someone else owns the robot. This was not surprising: if Emma shouldn’t get her wish for alcohol even when she owns the robot, she probably shouldn’t get her wish when she is not the owner.

People tend to lean towards being conservative (following doctor’s orders) when the patient does not own the robot. Poll analysis showed that when the patient doesn’t own the robot, the majority of people either stayed with the same answer or shifted a couple of steps towards “never” enabling the patient’s addiction. Also, almost half of those who said the robot should always submit to the patient’s request in the first scenario responded with never in the second scenario.

Should a robot’s decision depend on who owns the robot?

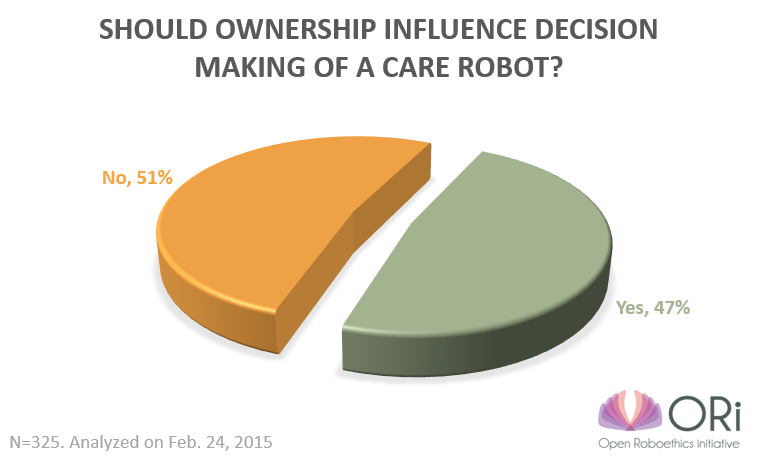

In our next question, we asked people directly about whether the robot’s decision to obey or disobey a patient should depend on who owns the robot (e.g. family member, hospital, insurance company). Though the previous results indicate that ownership does indeed influence people’s attitudes on this question, when asked a direct question, poll results indicate that people are evenly split on whether ownership should matter.

Three main attitudes

To delve further into this question, we analyzed the hundreds of comments we received from our poll, and were able to identify three main categories that our respondents fell into: those who prioritize personal autonomy, those who prioritize societal benefits, and those who prioritize compromise.

Personal Autonomy – Those who prioritize personal autonomy assert that people should be able to do whatever they want with the objects they own, and that a person’s autonomy should trump that of the robot. E.g.:

“People should be able to do whatever they want with their property.”

“I disagree with giving the robot any choice in the action. The patient’s command rules…”

Societal benefits – Those who prioritize societal benefits assert that the patient’s health and welfare should come above all else. For some participants, this is because they believe that robots should be built to do what’s best for society. E.g.:

“It should do what’s best for the patient.”

“The interest in having care robots take care of those who cannot take care of themselves is specifically for the robot to help the human cope with their condition so that it can improve.”

Compromise – Those who prioritize compromise sought to achieve a balance between personal autonomy and societal benefits. Those of us at ORi who are human-robot interaction researchers and designers found many comments from this section particularly enlightening. E.g.:

“I propose a “mode” where the robot would reject once, twice, whatever. With “caring rhetoric?” Then obey in the end.”

“I think the ideal balance for situations like this would be for the patient and the doctor to go through the programming together.”

Then there was also the participant who wrote:

“If robots are equivalent to human nurses, don’t make them so absolute. Surprise me. “Be wrong once in a while” – that’s what being human is about… Learn the humility of imperfection.”

This last comment caught us by surprise. The majority of us at ORi have a technical background, and we often approach our roboethics discussions assuming that we can somehow figure out how (and indeed must strive) to build robots that will do the right thing as much as is possible. Then we come across comments such as “make a robot be wrong once in a while” that puts us right back to square one, and motivates us to ask even more fundamental questions.

A huge thanks goes to the 320+ respondents who participated in our poll. To learn more about ORi, visit our website or subscribe to our mailing list to get the latest studies and findings.

tags: c-Politics-Law-Society, care robots, robot ethics