Robohub.org

Showing robots how to drive a car… in just a few easy lessons

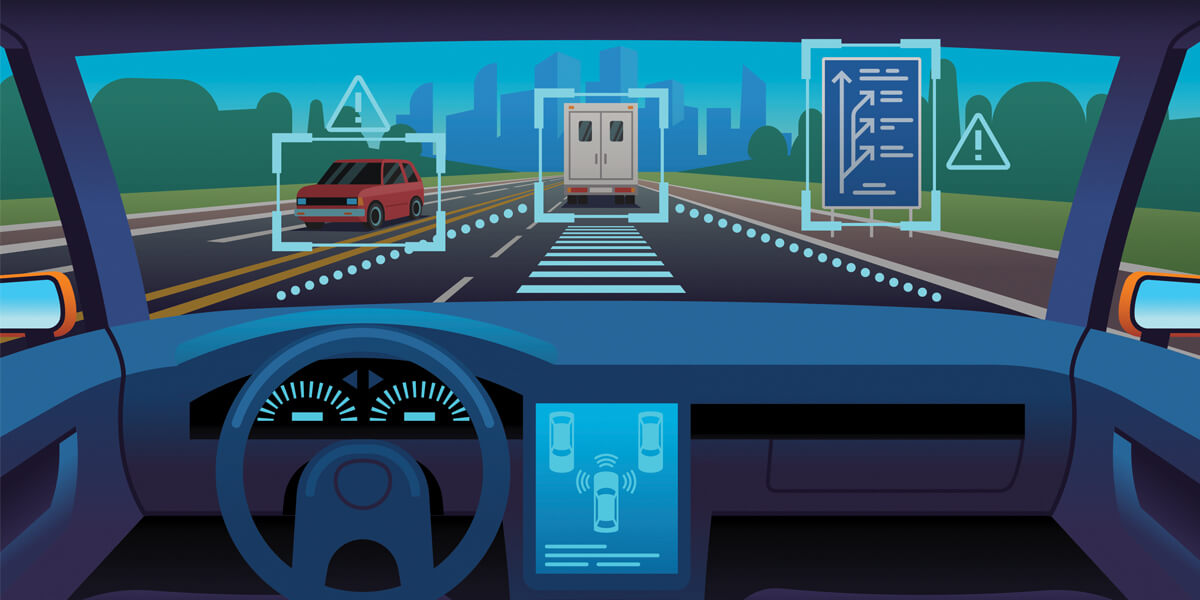

If robots could learn from watching demonstrations, your self-driving car could learn how to drive safely by watching you drive around your neighborhood. Photo/iStock.

By Caitlin Dawson

USC researchers have developed a method that could allow robots to learn new tasks, like setting a table or driving a car, from observing a small number of demonstrations.

Imagine if robots could learn from watching demonstrations: you could show a domestic robot how to do routine chores or set a dinner table. In the workplace, you could train robots like new employees, showing them how to perform many duties. On the road, your self-driving car could learn how to drive safely by watching you drive around your neighborhood.

Making progress on that vision, USC researchers have designed a system that lets robots autonomously learn complicated tasks from a very small number of demonstrations—even imperfect ones. The paper, titled Learning from Demonstrations Using Signal Temporal Logic, was presented at the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), Nov. 18.

The researchers’ system works by evaluating the quality of each demonstration, so it learns from the mistakes it sees, as well as the successes. While current state-of-art methods need at least 100 demonstrations to nail a specific task, this new method allows robots to learn from only a handful of demonstrations. It also allows robots to learn more intuitively, the way humans learn from each other — you watch someone execute a task, even imperfectly, then try yourself. It doesn’t have to be a “perfect” demonstration for humans to glean knowledge from watching each other.

“Many machine learning and reinforcement learning systems require large amounts of data data and hundreds of demonstrations—you need a human to demonstrate over and over again, which is not feasible,” said lead author Aniruddh Puranic, a Ph.D. student in computer science at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering.

“Also, most people don’t have programming knowledge to explicitly state what the robot needs to do, and a human cannot possibly demonstrate everything that a robot needs to know. What if the robot encounters something it hasn’t seen before? This is a key challenge.”

Above: Using the USC researchers’ method, an autonomous driving system would still be able to learn safe driving skills from “watching” imperfect demonstrations, such this driving demonstration on a racetrack. Source credits: Driver demonstrations were provided through the Udacity Self-Driving Car Simulator.

Learning from demonstrations

Learning from demonstrations is becoming increasingly popular in obtaining effective robot control policies — which control the robot’s movements — for complex tasks. But it is susceptible to imperfections in demonstrations and also raises safety concerns as robots may learn unsafe or undesirable actions.

Also, not all demonstrations are equal: some demonstrations are a better indicator of desired behavior than others and the quality of the demonstrations often depends on the expertise of the user providing the demonstrations.

To address these issues, the researchers integrated “signal temporal logic” or STL to evaluate the quality of demonstrations and automatically rank them to create inherent rewards.

In other words, even if some parts of the demonstrations do not make any sense based on the logic requirements, using this method, the robot can still learn from the imperfect parts. In a way, the system is coming to its own conclusion about the accuracy or success of a demonstration.

“Let’s say robots learn from different types of demonstrations — it could be a hands-on demonstration, videos, or simulations — if I do something that is very unsafe, standard approaches will do one of two things: either, they will completely disregard it, or even worse, the robot will learn the wrong thing,” said co-author Stefanos Nikolaidis, a USC Viterbi assistant professor of computer science.

“In contrast, in a very intelligent way, this work uses some common sense reasoning in the form of logic to understand which parts of the demonstration are good and which parts are not. In essence, this is exactly what also humans do.”

Take, for example, a driving demonstration where someone skips a stop sign. This would be ranked lower by the system than a demonstration of a good driver. But, if during this demonstration, the driver does something intelligent — for instance, applies their brakes to avoid a crash — the robot will still learn from this smart action.

Adapting to human preferences

Signal temporal logic is an expressive mathematical symbolic language that enables robotic reasoning about current and future outcomes. While previous research in this area has used “linear temporal logic”, STL is preferable in this case, said Jyo Deshmukh, a former Toyota engineer and USC Viterbi assistant professor of computer science .

“When we go into the world of cyber physical systems, like robots and self-driving cars, where time is crucial, linear temporal logic becomes a bit cumbersome, because it reasons about sequences of true/false values for variables, while STL allows reasoning about physical signals.”

Puranic, who is advised by Deshmukh, came up with the idea after taking a hands-on robotics class with Nikolaidis, who has been working on developing robots to learn from YouTube videos. The trio decided to test it out. All three said they were surprised by the extent of the system’s success and the professors both credit Puranic for his hard work.

“Compared to a state-of-the-art algorithm, being used extensively in many robotics applications, you see an order of magnitude difference in how many demonstrations are required,” said Nikolaidis.

The system was tested using a Minecraft-style game simulator, but the researchers said the system could also learn from driving simulators and eventually even videos. Next, the researchers hope to try it out on real robots. They said this approach is well suited for applications where maps are known beforehand but there are dynamic obstacles in the map: robots in household environments, warehouses or even space exploration rovers.

“If we want robots to be good teammates and help people, first they need to learn and adapt to human preference very efficiently,” said Nikolaidis. “Our method provides that.”

“I’m excited to integrate this approach into robotic systems to help them efficiently learn from demonstrations, but also effectively help human teammates in a collaborative task.”

tags: Automotive, c-Research-Innovation