Robohub.org

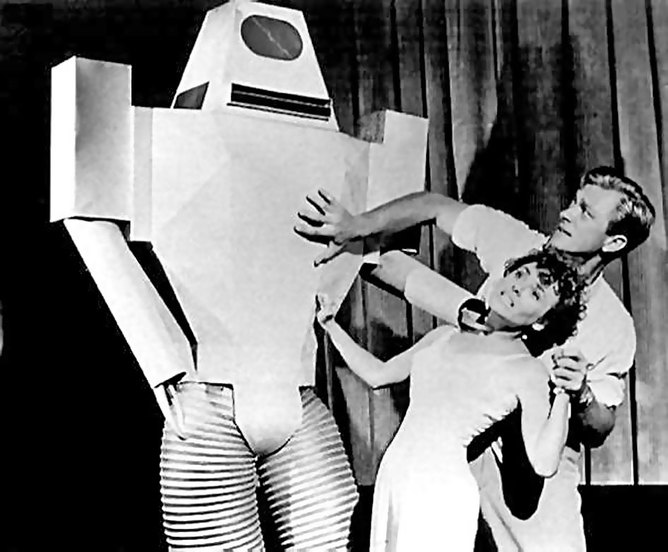

The truth is no stranger than fiction when it comes to robots

By Kathleen Richardson, University College London

Robots represent the cutting edge in science. For decades we have been promised a bright future in which these human-like machines will become so advanced that we won’t be able to tell the difference between them and us. But are technologists really dabbling in the unknown in their work or merely ripping a page out of their favourite sci-fi novel?

Robots existed in fiction long before science made them a reality. In the 1920s, Czech playwright Karel Čapek wanted to create a character that could reflect the dehumanisation of society, the obsession with production and the jubilant celebration of technological progress that often resulted in the horror of the battlefields.

Having already experimented with using different non-human characters like newts and salamanders to reflect on human life and existence, Čapek made “the Robot” a central character in his play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). The Robot was a particular kind of “other” who looked and acted like a human being but lacked something unique – feelings. It was not the product of a mother and father but of a production line. For Čapek, it seems, the robot is an inherently political character, a revolutionary even.

But even this was not the first time that artificial beings had been used by creative writers. The cultural narrative of creation goes back to a time when humans first began to craft objects from material things. Some of these objects were shaped to look like humans. Take the Venus figurines that date back at least 35,000 years, or dolls, which have long been more than just innocent playthings for children in some cultures. Dolls can be magical talismans and, for some, the miniature representation of the human form was a useful way to control the human adult it was supposed to represent. The particular ways in which humans are represented is culturally specific but the desire to represent is, and always has been, universal.

So what is the modern technology of robotics doing that is so different from all these fictional exercises in imitating the human form? The roboticists and technologists of today would have you believe that their work is grounded in scientific reality when they seek the next big breakthrough in artificial intelligence. Cyberneticians and futurologists make claims as if the issues they address were never before considered in human society. But they are in fact more swept up in fantasy than ever before.

All attempts to represent the human form tap into a timeless motivation to know who we are: the mystery of life, reproduction, childhood and attachments to other humans, animals and nature.

What is exciting about AI and technology is that these provide new ways of representing the human form. But the debate about what that means is so confused and ridiculous at times it can leave futurologists lost in their own fantasies. In the 1960s, Marvin Minsky was so optimistic about the new field of AI, he believed that, by the end of the 20th century, machines will outsmart human beings. This is, in part, what inspired Arthur C. Clarke when he speculated about the future of intelligence in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Ray Kurzweil is another case in point. In books such as The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, Kurzweil is forever predicting that we will merge with machines and be able to upload our “complete” consciousness into machines. This idea is emerging as the next big challenge in robotics but it could equally be viewed as a basic feature of human cultural existence.

I’m “uploading” my consciousness right now into this article. A visual artist, when she paints is also “uploading” her consciousness. Consciousness is just another way of saying psychic life – the life and impulses of the individual as a member of a family and collective. Arguably, any human being that has ever created anything has transferred aspects of their consciousness to artificial materials.

The fiction is now being created by the scientists. AI roboticists are given a free reign to project any fantasy they like about their technology and how it will irrevocably change what it means to be human. We have been asking the same question since the beginning of time in different ways. The only difference now is that those building the robots and AI systems believe their work is unique rather than part of an ongoing process and also stand to acquire a lot of money in the process.

Kathleen Richardson is affiliated with Department of Anthropology, University College London

This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Read the original article.

tags: AI, c-Arts-Entertainment, cx-Politics-Law-Society