Robohub.org

Project Hieroglyph: Science fiction for better futures

It seems like our most popular visions of the future always end with environmental collapse, authoritarian oppression … and the ever-popular zombie apocalypse. Science fiction, what Clive Thompson called “the last great literature of ideas,” seems to function today primarily as a literature of warning, of cautionary tales and parables of technology run amok.

What if we could also use science fiction to inspire hopeful thinking about the future, to imagine how technology could be a tool to help us solve our most pressing challenges, instead of being the purveyor of our destruction or a symbol of our hubris? Project Hieroglyph, founded by science fiction visionary Neal Stephenson in 2012 and headquartered at Arizona State University’s Center for Science and the Imagination, seeks to use science fiction to restore the creative, practically ambitious thinking about technology that made Golden Age science fiction so powerful and compelling.

The project’s first anthology, Hieroglyph: Stories and Visions for a Better Future (William Morrow/HarperCollins) features hopeful visions of the near future, grounded in real science and technology, created by top science fiction authors like Stephenson, Cory Doctorow, Elizabeth Bear, and Bruce Sterling, and scientists, technologists, and other experts in fields ranging from robotics and space exploration to education, sustainability, and neuroscience. (Disclaimer: I work at the Center for Science and the Imagination, and am one of the project managers for Hieroglyph.) We sometimes call this “science fiction of the present” or “science fiction of five minutes from now,” because the stories feature technologies – from a 20 kilometer steel tower to crowdfunded 3D printing robots creating a lunar base from moon dust to a global network of drone pilots protecting wildlife from poachers – that we could start building today, if we had the right story to tell about how and why.

The fundamental idea driving Project Hieroglyph is this: if we want a better future, we need to start by crafting better stories , better dreams. Major challenges like climate change, world hunger, and many of our most deadly infectious diseases are well understood. What holds us back from implementing solutions on a global scale is a lack of social and political will – fundamentally, a lack of imagination. We need stories that engage our collective imagination and inspire us to reallocate resources, change our priorities, and do something different, ambitious, and transformative.

When Stephenson talks about a “Hieroglyph,” he means an icon, like Asimov’s robots, Heinlein’s rocket ships, and William Gibson’s cyberspace, that “supplies a plausible, fully thought-out picture of an alternate reality in which some sort of compelling innovation has taken place” (read more in his article “Innovation Starvation“). Hieroglyphs become deeply etched in our cultural consciousness and shape generations of actual research. For example, it’s impossible to work on robotics without grappling with Asimov’s Three Laws.

Project Hieroglyph also challenges science fiction writers to collaborate deeply with researchers working at the cutting edge of knowledge, not just as fact checkers, but as equal partners. Stephenson’s story about a 20 kilometer tall steel tower, for example, was created in collaboration with Keith Hjelmstad, a professor of structural engineering at Arizona State University, and the idea is filtering back into Keith’s teaching, research, and work with students who are exploring how super-tall structures can cope with punishing jet stream winds and exotic upper-atmosphere weather conditions.

A great science fiction story can act as a first prototype (an idea developed by Intel’s futurist Brian David Johnson, one of our collaborators), a napkin sketch of a possible technological solution, to explore how the technology might affect communities, economies, and individuals. The best stories are also invitations, bringing people from a variety of perspectives together to have a conversation about whether we should pursue certain innovations, how we should use our vast technological capabilities, and what limits and regulations need to govern emerging technologies. At Project Hieroglyph we believe that weaving a human story around a whiz-bang technological idea is an important step in beginning to understand its social, cultural, and ethical implications, and to give a broad range of people an opportunity to respond, with enthusiasm, curiosity, caution, or consternation. In this spirit, each story in our anthology is coupled with a “story page” on our web platform that features expert responses, links to additional information, and most importantly, discussion forums that enable readers, experts, and skeptics to weigh in and contribute their own ideas.

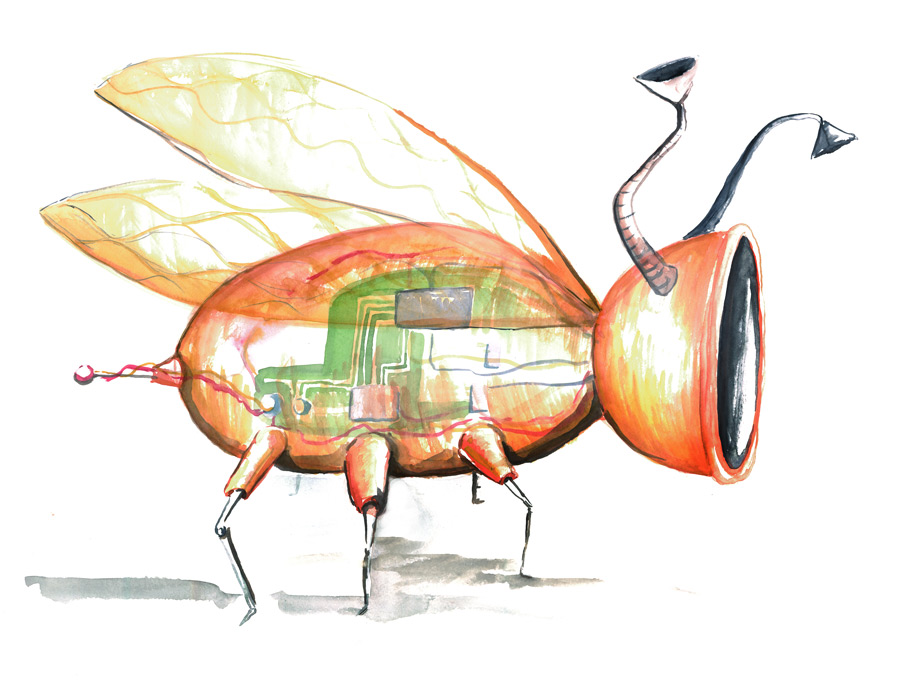

We’re excited to welcome in Robohub community members to Project Hieroglyph, especially because several of the stories in our first anthology engage with the incredible possibilities of emerging robotics technologies. Cory Doctorow’s novella “The Man Who Sold the Moon” imagines how crowdfunding, the DIY culture, and 3D fabrication can open up new possibilities for democratized robotic forays into space. Gregory Benford’s “The Man Who Sold the Stars” (a lot of Heinlein readers contributed to this one!) imagines a future where robotic mining of asteroids and comets enables humans to extend our reach throughout our solar system and beyond. Lee Konstantinou’s “Johnny Appledrone vs. the FAA” and Brenda Cooper’s “Elephant Angels” consider how drones, currently a major bogeyman haunting our collective imagination, might be used for good. Vandana Singh’s “Entanglement” imagines self-organizing networks of robots scouring the floor of the Arctic Ocean and plugging methane leaks that threaten to exponentially accelerate climate change.

Project Hieroglyph has a network of amazing writers, artists, scientists, and engineers engaged in creating stories that make transformative change feel possible. But we know that we can’t accomplish anything significant without you. These stories are arenas for conversation, collaboration, and creativity, and they are designed to spawn real-world research projects, inventions, and solutions. We need your help transforming these Big Ideas into new collective realities. Won’t you join us?

To learn more about Project Hieroglyph and join the community, visit http://hieroglyph.asu.edu. Check out a video trailer for the project here:

http://vimeo.com/105817777

Read free excerpts from the book here, here, and here.

tags: Book, c-Arts-Entertainment, robohub focus on arts and entertainment