Robohub.org

RoboBees take to the sky – and now the sea

By Leah Burrows | SEAS Communications

By Leah Burrows | SEAS Communications

Engineers have been trying to design functional aerial-aquatic vehicles for decades with little success. The biggest challenge is conflicting design requirements: aerial vehicles require large airfoils like wings or sails to generate lift while underwater vehicles need to minimize surface area to reduce drag.

To solve this, engineers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS) and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University took a clue from puffins. The birds with flamboyant-colored beaks are one of nature’s most adept hybrid locomotors, employing similar flapping motions to propel themselves through air as well as through water to dive for fish.

“Through various theoretical, computational and experimental studies, we found that the mechanics of flapping propulsion are actually very similar in air and in water,” said Kevin Chen, a graduate student in the Harvard Microrobotics Lab at SEAS. “In both cases, the wing is moving back and forth. The only difference is the speed at which the wing flaps.”

RoboBee: From Aerial to Aquatic from Wyss Institute on Vimeo.

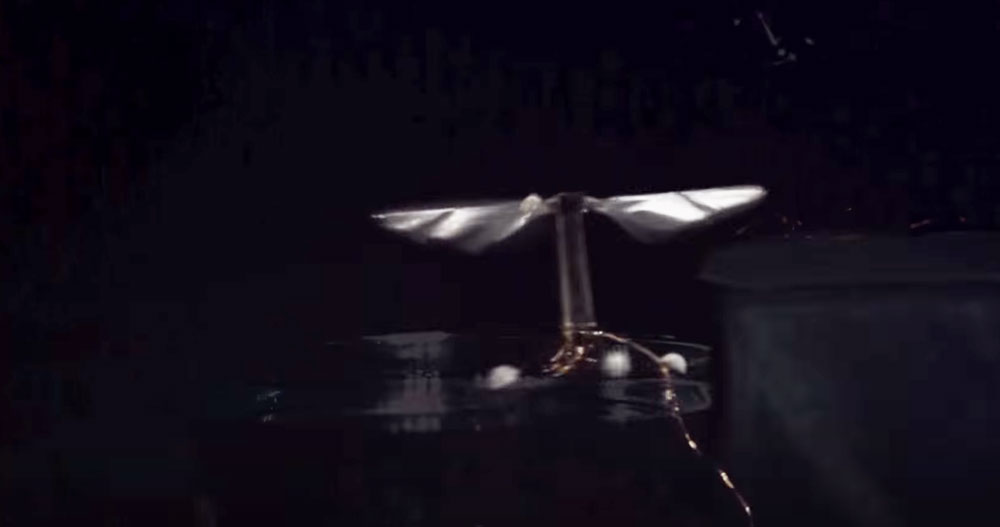

Applying this in the lab, the team of researchers at SEAS and Wyss have demonstrated the first flying, swimming, insect-like robot — paving the way for future duel aerial aquatic robotic vehicles. The aerial-aquatic robot is an adaptation of the previously developed “RoboBee”, a microrobot smaller than a paperclip that flies and hovers like an insect, flapping its tiny, nearly invisible wings 120 times per second.

The new research was presented recently in a paper at the International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems in Germany, where first author Chen accepted the award for best student paper. The paper was co-authored by SEAS/Wyss graduate student Farrell Helbling, SEAS/Wyss postdoctoral fellows Nick Gravish and Kevin Ma, and Robert J. Wood, who is the founder of the Harvard Microrobotics Lab, the Charles River Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences at SEAS, and a Core Faculty Member at the Wyss Institute.

In order to make the transition from air to water, the team first had to solve the problem of surface tension. The RoboBee, designed in Wood’s lab, is so small and lightweight that it cannot break the surface tension of the water. To overcome this hurdle, the RoboBee hovers over the water at an angle, momentarily switches off its wings, and crashes unceremoniously into the water in order to sink.

Next, the team had to account for water’s increased density. “Water is almost 1,000 times denser than air and would snap the wing off the RoboBee if we didn’t adjust its flapping speed,” said Helbling, the paper’s second author.

The team lowered the wing speed from 120 flaps per second to nine but kept the flapping mechanisms and hinge design the same. A swimming RoboBee changes its direction by adjusting the stroke angle of the wings, the same way it does in air. Like a flying version, it is still tethered to a power source. The team prevented the RoboBee from shorting by using deionized water and coating the electrical connections with glue.

While this RoboBee can move seamlessly from air to water, it cannot yet transition from water to air. Solving that design challenge is the next phase of the research, according to Chen.

“What is really exciting about this research is that our analysis of flapping-wing locomotion is not limited to insect-scaled vehicles,” said Chen. “From millimeter-scaled insects to meter-scaled fishes and birds, flapping locomotion spans a range of sizes. This strategy has the potential to be adapted to larger aerial-aquatic robotic designs.”

“Bioinspired robots, such as the RoboBee, are invaluable tools for a host of interesting experiments — in this case on the fluid mechanics of flapping foils in different fluids,” said Wood. “This is all enabled by the ability to construct complex devices that faithfully recreate some of the features of organisms of interest.”

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.

tags: c-Research-Innovation, cx-Aerial, Robobee, Wyss Institute