Robohub.org

Science, startups and industry at RSS2014 (Part 2)

The 10th annual Robotics Science and Systems conference (RSS14) is on at the University of California, Berkeley, July 12 to 16, and we are picking up where we left off yesterday on our coverage of the ‘Academia, Startups and Industry’ workshop. Opening with a plenary from Vijay Kumar, U Penn, the morning session asked industry experts from different domains including automation, manufacturing, automobile, aerospace, healthcare to talk about the next-generation of problems for robotics to address.

The other workshop speakers were; Erik Nieves (Yaskawa); Rainer Bischoff (KUKA Laboratories GmBH); Phil Freeman (Boeing); Murad Kurwa (Flextronics); and Paul Millman (Intuitive Surgical). They talked about the need for new types of robots and capabilities, the research directions that academia could take, and the potential for greater industry-academic collaboration.

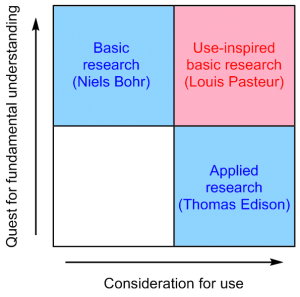

Kumar described the approaching challenge for robotics as the need to find alternative funding when pure research funding dries up. Kumar believes that robotics is better able to weather this defunding trend than many other disciplines due to the applied nature of robotics. However, he doesn’t want the field of robotics to stop doing fundamental research. Kumar suggests that researchers focus on Pasteur’s quadrant, avoiding Edison and Bohr, as defined by Donald Stokes in his 1997 book, “Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation“.

Kumar described the approaching challenge for robotics as the need to find alternative funding when pure research funding dries up. Kumar believes that robotics is better able to weather this defunding trend than many other disciplines due to the applied nature of robotics. However, he doesn’t want the field of robotics to stop doing fundamental research. Kumar suggests that researchers focus on Pasteur’s quadrant, avoiding Edison and Bohr, as defined by Donald Stokes in his 1997 book, “Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation“.

Erik Nieves, Yaskawa “Robotics is changing. Are the industrial guys listening?”

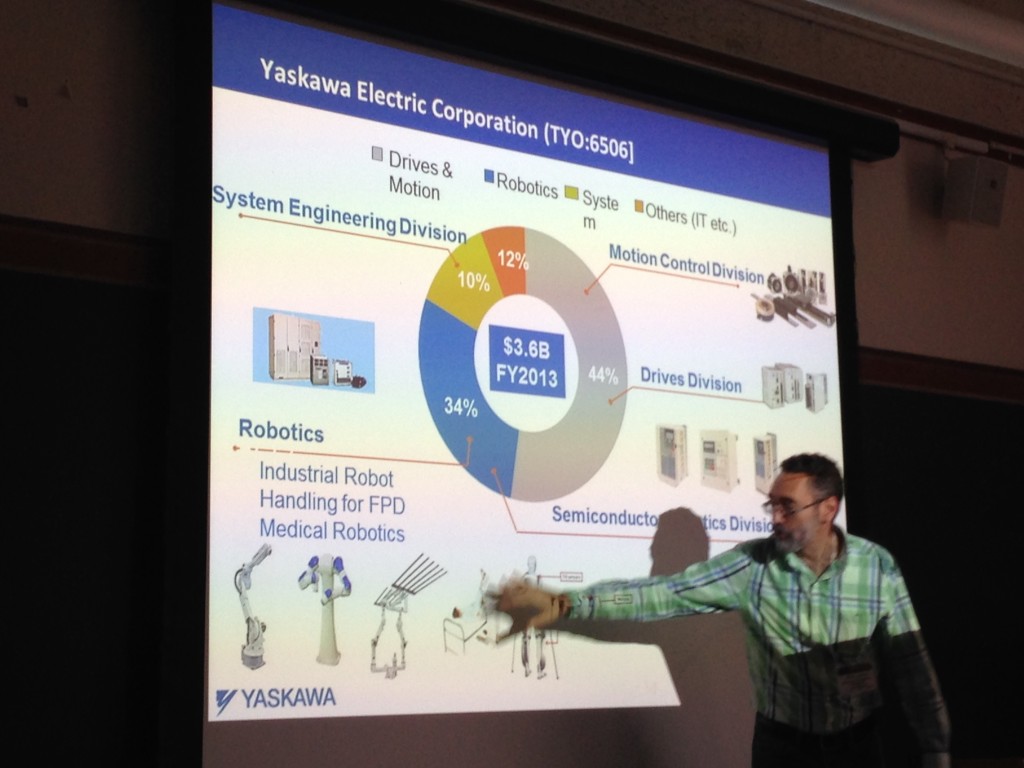

Erik Nieves opened by saying that commercial robotics companies have an obligation to their shareholders to pay attention to the changes in robotics because the big four robotics companies are currently overly dependent on the automotive industry. The SAR of vehicle sales controls the overall company performance. 1/3 of Yaskawa’s total business is effectively one customer and this doesn’t make for long term viability.

“We may have billion dollar sectors, but we need to think like startups.” [Erik Nieves]

The best definition of the advanced manufacturing changes that have occurred in last decades comes from Paul Fowler, from NACFAM, the National Association of Advanced Manufacturing.

“The Advanced Manufacturing entity makes extensive use of computer, high precision, and information technologies integrated with a high performance workforce in a production system capable of furnishing a heterogeneous mix of products in small or large volumes with both the efficiency of mass production and the flexibility of custom manufacturing in order to respond quickly to customer demands.” [Paul Fowler]

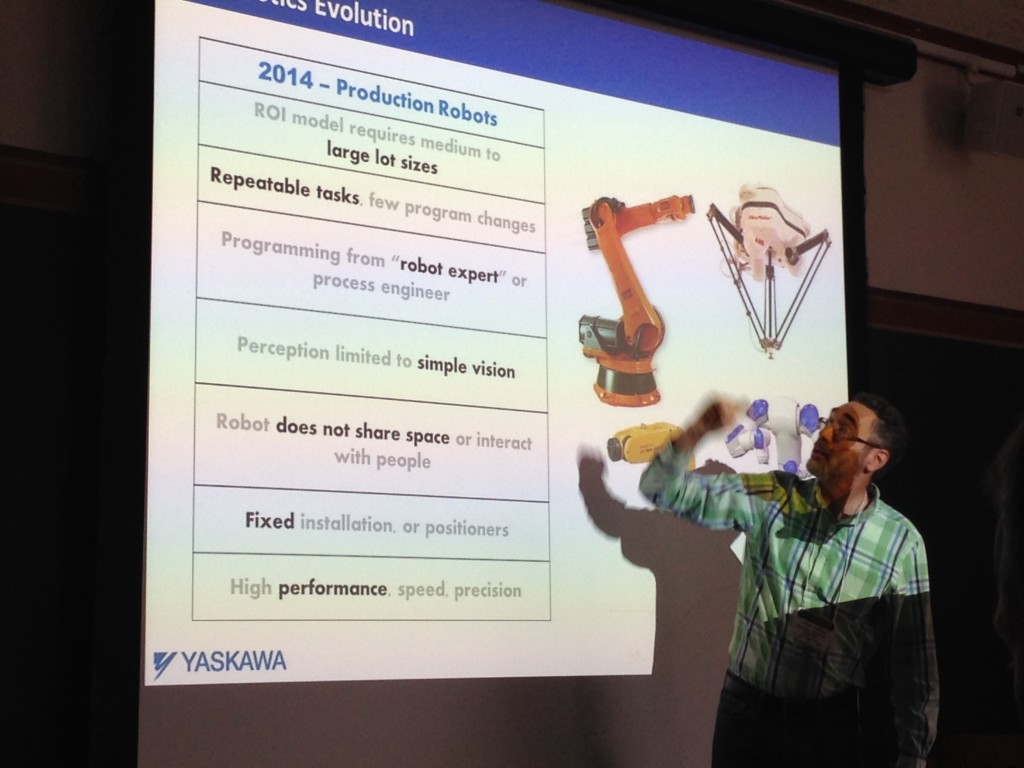

“Robotics companies are good at the efficiency of mass production but not at the flexibility of custom production. We need to be more agile.” says Nieve. “In the next 6 years, we will transition from robots where ROI require large lot sizes, repeatable tasks and expert programming, to robots that can do one-off tasks, that require much lower investment and are easily programmed and integrated. They are able to share space with humans and are mobile or freely deployable.”

These collaborative robots look a lot more like labor than machines. They respond to demand and move to the work. The only thing that is similar with today’s robots is high performance, speed and precision. By 2020, ‘production partner’ robots will be a significant part of the industrial robot landscape.

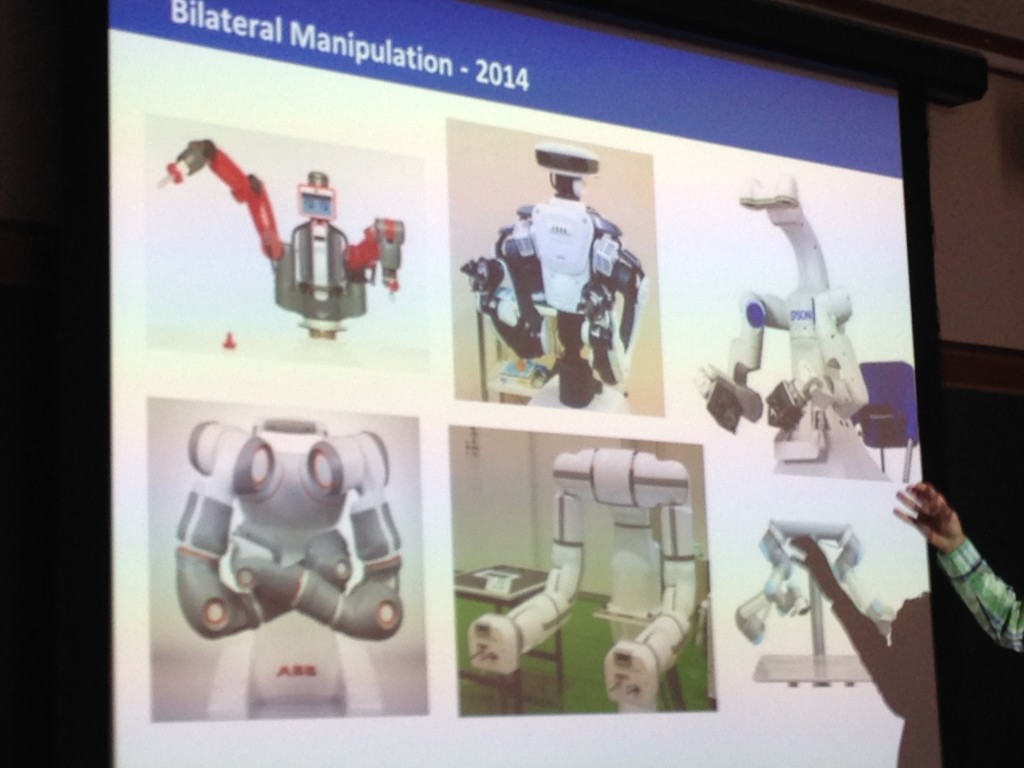

An issue slowing the roll out of robots in the US is a lack of systems integrators with developer skills. ROS is great because of the wide adoption and it will be useful for developing for the new two armed robots. 80% of work in some factories is automated, but only on one side of the factory. Final assembly is usually all done by people. Those are jobs that require two arms, working on flimsy, floppy materials, jobs easily done by people. Dextrous manipulation is hard to program for, and we need better tools from the community.

The robot industry is looking for adjacent markets, and it has to be manufacturing-like and look a manufacturing as a process, not as an industry. For example, tasks that require similar work, ie. lab work with pipettes, or putting things in boxes – activities that require logistics. Staying with the single arm paradigm puts additional stress on the end effector; stress that’s shared with two effectors become far more dextrous. Kitting is a big part of the future where every large manufacturer is it’s own distribution center.

Yaskawa is excited about automatically generated programs, said Nieve. “CAD/CAM has just shifted paradigm from tool to computer. We want to generate it on the fly. Mobility is a force multiplier for robots. When we can send a mobile autonomous robot to another machine to do a job, and that robot can register its position and work appropriately. Robots become labor. They move from place to place.”

Nieve said that robotics will continue to advance in lock step with developments in adjacent fields, particularly consumer electronics, and that the application space will continue to widen as robots acquire more human-like form and skill. And yet we still need better wrists and more coding skills. Combining the precision and strength of robots with the perception and decision making of humans is the future of collaborative work.

Nieve also pointed out that right now, the seeds of the greatest generation of technicians, engineers, and roboticists are being laid and will bear fruit. “We coined the term mechatronics in 1969 to capture the electronic control of mechanisms. That was a generation ago. But now roboticists come from everywhere, we are makers, we are robot competition teams. RSS had only a few hundred people a few years ago and is now almost a thousand.”

Nieves closed his talk with a mention of the upcoming RIA International Collaborative Robots Workshop, which will be held in Silicon Valley on September 30, 2014.

Rainer Bischoff – Kuka “Innovation through collaboration”

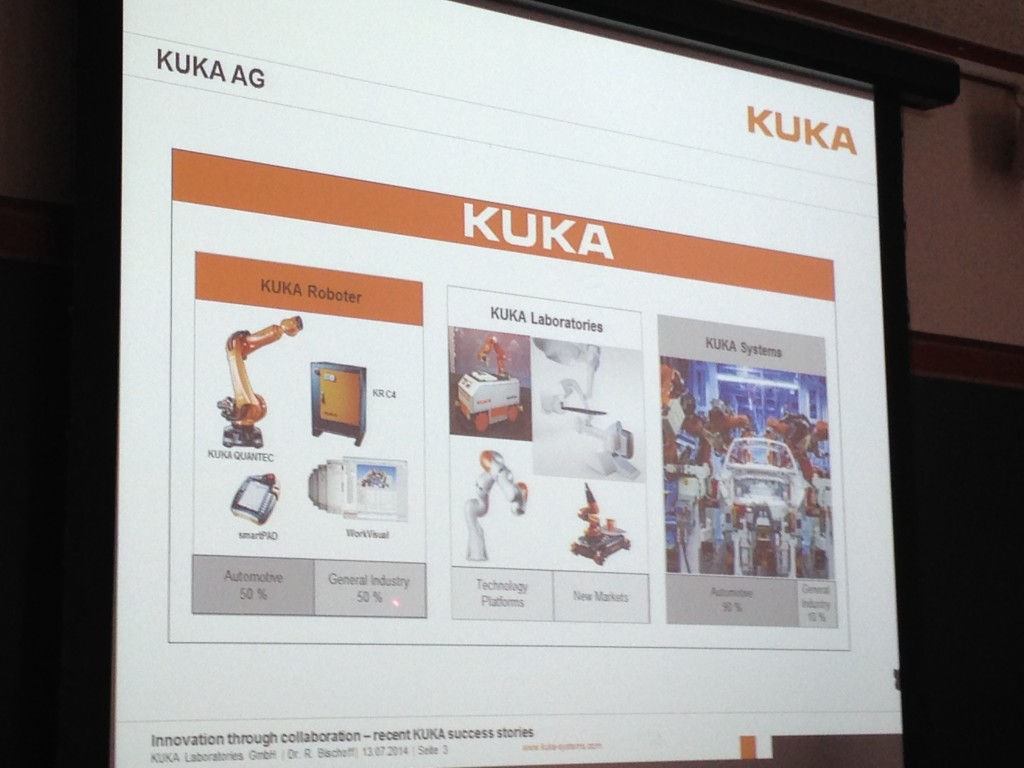

KUKA is the pure play robotics company. In other words: they only make robots, unlike the other major robotics companies, which also make drives or motors. KUKA labs was founded 3 years ago to help find and build new markets because 90% of KUKA’s line is automotive.

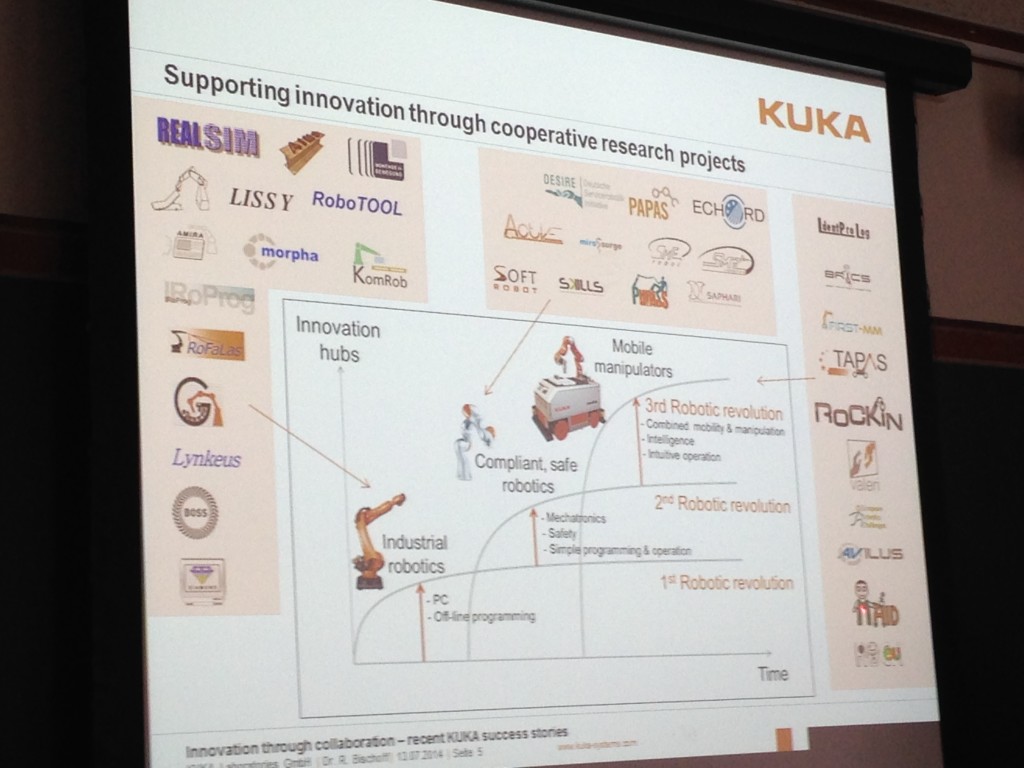

Bischoff sees 3 different robotics revolutions:

- PC bringing flexibility into industrial robotics world

- compliant-safe robotics

- combined mobility and manipulation

Why KUKA is doing collaborative research projects:

- new contacts to industrial and academic partners

- technology scouting

- know-how and competence buildup

- preparation of technology transfers

- working on long term r&D

- reduced financial risk – funding from govt for coprojects

While Bischoff said that work is still needed to overcome mental barriers at KUKA and with customers, he pointed to several successful collaboration examples:

- RealSim 2000-02 – where KUKA collaborated with competitors in a research pre development stage.

- PAPAS 2003-6 – development of RobotWorker and DLR Robot Controller, which has now become a real product – last Automatica. The robot will not extend from virtual walls that you set, there is collision avoidance, work cells can be set up without fences. But it can still bring to bear the forces that are needed to assemble a gear box.

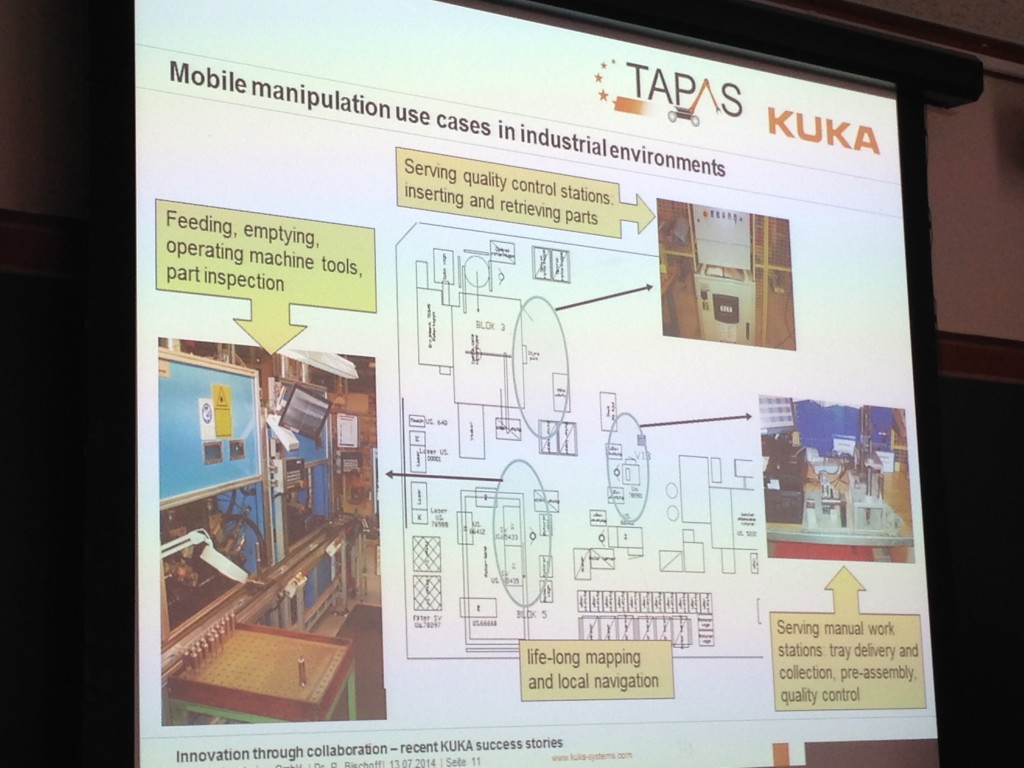

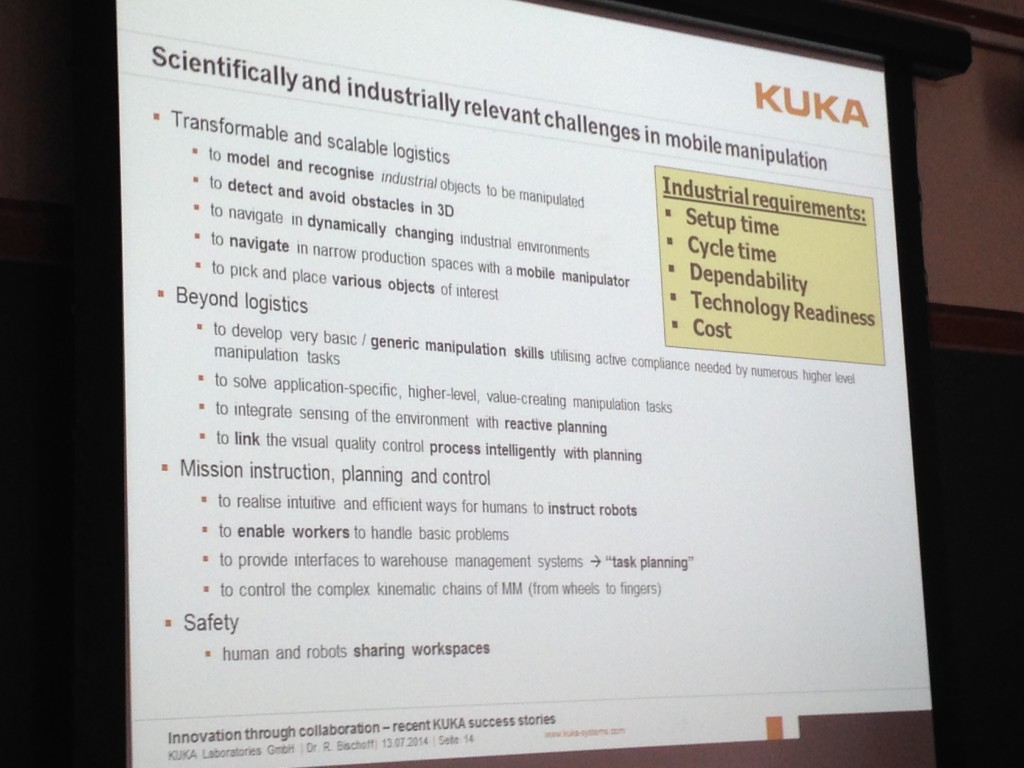

- TAPAS 2010-14 – mobile manipulation with use cases in industrial environments using a mobile platform and lightweight arm. Navigation on shop floor is basically solved barring the lifelong mapping. Paths are far from optimal at the moment. So far it is much too slow to compete with ordinary workers.

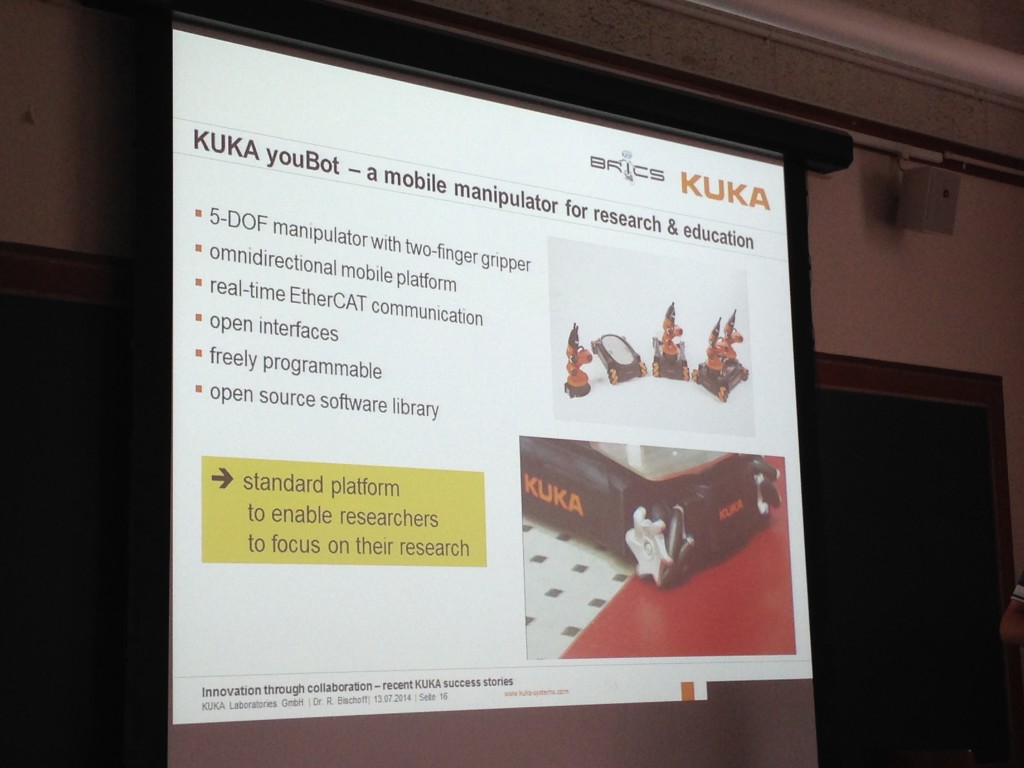

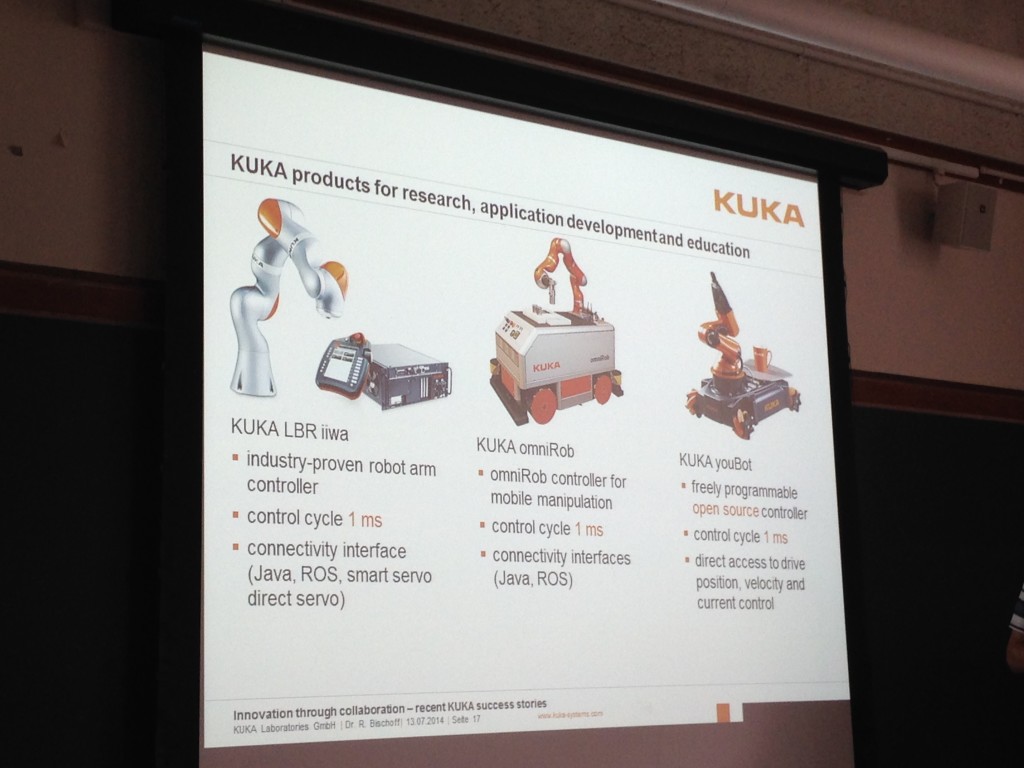

Bischoff says that work is still needed on mobile manipulation for industry. KUKA is trying to speed up this process by making research robots that scale easily to the real industrial models but are much more affordable.

“KUKA is supplying academic researchers with platforms so they can focus on research and not reinvent robots.” [Rainer Bischoff]

Bischoff also pointed to initiatives like the inaugural KUKA Innovation Award, which was first awarded this year to a team from the University of Zurich that used a drone to guide a Youbot through a disaster relief scenario.

Another project is RoCKIn, an EU project that will be run over the next three years, consisting of robot competitions, symposiums, educational RoCKIn camps and technology transfer workshops. Their mission is to act as a catalyst for smarter, more dependable robots, and they are doing this by building upon the principles of challenge-driven innovation laid down by RoboCup, facilitating cognitive and networked robot systems’ testing, and streamlining research and development through standardized testbeds and benchmarks.

Also, since 2012, Bischoff has been Vice-president industry of euRobotics aisbl – the European Robotics Association. In these capacities he has been setting the Strategic Research Agenda for European robotics until 2020, successfully establishing closer links between robotics academia and industry, and promoting European robotics as a whole.

tags: c-Events, cx-Business-Finance, cx-Research-Innovation, startups