Robohub.org

Turning the lens on robotics reporting: An interview with New York Times technology reporter John Markoff

If you are working in the field of robotics or AI, you may be used to fielding calls from journalists wanting to better understand the technology. But not all journalists are created equal. Pulitzer-Prize-winning John Markoff (@markoff) has been covering the technology beat at the New York Times for almost three decades, and recently published Machines of Loving Grace – a book that chronicles the evolution of computer science, robotics and AI. In this interview we turn the lens around and ask Markoff about what motivates his interest to report on robotics, and how he sees trends in robotics today being informed by people and events from the past.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

[HS] Can you tell us about your early days writing about the fields of AI and robotics?

[JM] I began writing about Silicon Valley in 1977 and spent most of my time writing about personal computing and the Internet. In the ‘80s there was a lot of controversy around the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) and many computer scientists and AI researchers were opposed to it – it was the first big AI issue in the news. Then in 2004 there was the DARPA autonomous vehicle challenge, and I began covering those events.

Engelbart’s prototype of a computer mouse, as designed by Bill English from Engelbart’s sketches. Image: Wikipedia via Macworld

It wasn’t until a bit later that I really made AI and Robotics my first interest, though. I’d covered computer security for the New York Times forever, but I began feeling that I’d written the same story just too many times. I needed to do something different, and it seemed like AI and robotics were making more progress.

I’ve always loved the social history of the Valley, and trying to understand how things are connected there. Often technologies will bubble around for decades before they actually gain broad consumer acceptance. Look at the mouse, for example. Engelbart invented it in ’64 but it really didn’t become a mass consumer product until Microsoft Windows and Mac adopted it 20 years later. I’m interested in what causes things to gain acceptance even though there were people who believed in them for years beforehand.

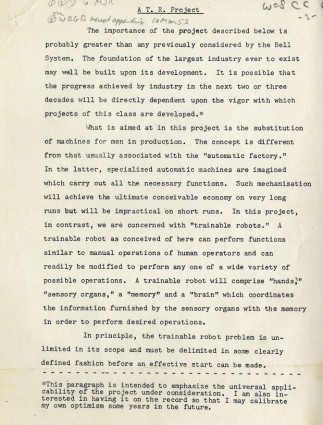

There are other examples … In 2010, the historian David Brock came across a 1951 memo written by William Shockley describing an “Automatic Trainable Robot”. Shockley had always been known for his work on transistors, but what the memo showed was that he had really set out to build a robotics company. To discover that early ideas in robotics were at the core of creating Silicon Valley was a bit of a revelation that nobody had really noticed until then.

Shockley’s 1951 memo to president of Bell Labs Mervin Kelly described an “automatic trainable robot” that sounds eerily similar to trainable products on the market today, such as Rethink’s Baxter. For more details, see the IEEE Spectrum article by David Brock How William Shockley’s Robot Dream Helped Launch Silicon Valley.

Your book describes a funny anecdote around that revelation … when Rod Brooks shared that memo with his employees and asked them to guess when it had been written…

Rod gave the memo to his employees, and nobody could figure out the timing of it, because if you just read the memo and don’t think about the date, it reads like a product description of Baxter. So here we have an idea for a “trainable robot” from 1951 … and 65 years later it looks like the timing is finally right.

Machines of Loving Grace starts out describing the tension between two researchers doing early work in computer science – John McCarthy and Douglas Engelbart – whose work eventually led to the creation of two philosophical “camps” in AI research. What was that tension about?

In the ‘60s McCarthy was involved in setting up the Stanford AI Laboratory, and Engelbart set up the Augmentation Research Center at SRI. They were each were about a mile from Stanford, but they had very different approaches. Whereas McCarthy had set out to build a working “artificial intelligence” that could simulate human capabilities (he thought this could be done within a decade), Engelbart was going in the opposite direction – he wanted to use technology to augment intellectual workers.

I came to realize that these two approaches – artificial intelligence (AI) and intelligence augmentation (IA) – went in two philosophically different directions … and that two distinct research communities emerged from those early laboratories – communities that don’t really speak to each other.

The paradox we see now is that the same technologies that extend our abilities can also displace us – and that was the puzzle I wanted to solve in my book.

There were several key figures in your book – Norbert Wiener and McCarthy come to mind – who really broke over differences in their philosophical approach to AI … Can you describe what was at the root of their polarization?

Read Frank Tobe’s review: New book by John Markoff explores common ground between humans and robots

Wiener was an interesting character – an outlier in his day, and rather eccentric.

In 1948 Wiener wrote ‘Cybernetics’, a book that outlined his approach to control and communication engineering. That work led him to believe that it was possible that humans could one day be designed out of the future, and so two years later he wrote a second more philosophical book called the ‘Human Use of Human Beings‘ about the AI/IA dichotomy, where he attempted to lay out the choice we have in terms of how we use technology.

At that point, technological unemployment was a new concern. Industrial automation had already been happening for decades, but Wiener was the first one to really understand the potential of software-controlled machines and he brought that alarm to the US labour movement. He actually wrote letters to many labour leaders to warn them that the technology was going to have an impact on the workforce, saying “This may end up destroying much of your union membership’s jobs.”

We know Wiener was a very controversial character within the engineering and academic communities; he had lots of enemies and his ideals were never mainstream. He was seen as a radical, going all the way back to his opposition to the technical community designing weapons in the wake of World War II.

On the other hand, McCarthy was very clear about saying that he deliberately coined the term “artificial intelligence” in order to set his ideas apart from Wiener. He felt that Cybernetics leaned too far towards the analogue. On a personal level, McCarthy really disliked Wiener, too; he thought that Wiener was bombastic and a bore, and he wanted nothing to do with him.

So there was this tension right at the root of artificial intelligence, and it has all kinds of significance for the field.

For the most part your book chronicles events that take place in the US. Was the same tension between AI and IA happening in other places, too?

That’s an interesting question. Cybernetics was more appealing to the Europeans, and there are Departments of Cybernetics in universities across Europe to this day. I am fascinated by that, even though I really did focus on the US in my book.

Sir James Lighthill. Image via Wikipedia. Watch the BBC Lighthouse Debates on YouTube.

AI actually had its first big failure not in the US but in England as a result of Lighthill Report, which assessed the claims made by the AI researchers in the early 1970s and then cut off government funding for their research, causing what we now call the “AI Winter”. That collapse of funding had a big impact on many people’s careers. Geoffrey Hinton for example is now a well-known Google researcher, and is one of the key figures in development of advance neural net technologies, but early in his career he really was an outcast as a result of that report.

Then there was Joseph Weizenbaum, who had a similar outlook to Wiener. He ran the famous ELIZA experiment at MIT and was aghast that a simple text bot was able to convince his students that they were having real conversations with it. In his book ‘Computer Power and Human Reason’ he was very critical of AI research on a philosophical and ethical level for ignoring human values. He left the US disgusted, and ended up being much more widely accepted in Europe.

What about Japan? Fast forwarding to the present, your book mentions Toyota’s current corporate philosophy of kaizen (or “good change”) as a shift that suggests there are limits to automation. Can you describe that philosophy and how it’s influenced Toyota’s policies?

While Toyota had at one time been pushing towards fully automated assembly lines, more recently they have begun to systematically put humans back into their manufacturing processes. They have come to see that if you fully automate a production line, it might be extremely reliable, but it’s frozen … an automated assembly line doesn’t really improve.

But skilled workers who are on the production line are intimately familiar with the manufacturing process, and can suggest ways to improve efficiency and productivity. So Toyota is rebalancing automation with craft in order to get a more cooperative relationship between humans and robots.

In September 2015 Toyota announced a substantial investment in robotics and AI research to develop “advanced driving support” technology, with former Program Manager of DARPA’s DRC Gill Pratt directing the overall project as Executive Technical Advisor. Toyota will allocate USD$50M over the next five years in a partnership with MIT’s CSAIL (headed by Daniela Rus) and Stanford’s SAIL (headed by Fei-Fei Li) to develop research facilities in Stanford and Cambridge. Photo: Kathryn Rapier

What’s interesting is that just this past fall Toyota invested in the AI departments of both MIT and Stanford to do research on an intelligent car that they clearly describe as being on the IA side of the AI-IA debate. They are not looking to build pure self-driving cars, but instead want to give you a kind of guardian angel that will watch over you as you drive. They really want to design humans “in” rather than design them “out”.

I spend a lot time with the AI community in my research, and I think half of the field really feels strongly that you should use AI technologies in an IA format, keeping humans in the loop. People like Adam Cheyer, Eric Horvitz and Tom Gruber are all well-known AI researchers who see Engelbart as their hero. Horvitz in particular feels strongly about approaching things from that direction.

In 2009 after the AAAI Meeting on Long Term AI Futures you wrote an article for the New York Times with the headline ‘Scientists Worry Machines May Outsmart Man‘. More recently, covering the DARPA challenge, your headline was ‘Relax, The Terminator is Far Away’. Has your perspective on robotics and AI changed in that time period?

The AAAI Alisomar meeting was really motivated by Eric Horwitz in response to WIRED article the founder of Sun Microsystems Bill Joy wrote in 2000 about Why the Future Doesn’t Need Us, where he raised concerns about AI and robotics as threats to human survival.

Horvitz felt that he needed to respond to Joy’s concerns, so in 2009 he called together a group of the best AI researchers in the country to explore the issue of how fast AI technologies were developing and whether they indeed posed a serious threat to humanity. That was where the first headline came from, and I was really a messenger in that case.

Funny enough, the final report from the meeting was somewhat anti-climactic: they basically came to a consensus of that the kind of scenario Joy had sketched out was not an immediate worry.

Funny enough, the final report from the meeting was somewhat anti-climactic: they basically came to a consensus of that the kind of scenario Joy had sketched out was not an immediate worry.

Now fast-forward to last year, when my article about the DAPRA Robotic Challenge came out. This was toward the end of the renewed AI debate that had just been touched off by Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk, Stuart Russell, Nick Bostrum, and others at the Future of Life Institute who were arguing that, based on half a decade of success in the neural network community, they foresee an exponential increase in the capability of machines coming in the near future.

But many computer scientists think that the possibility of self-aware thinking machines is vastly overstated, and my experience watching the DARPA Robotics Challenge supported that view. You just had to look at the falling robots, and the fact most of them couldn’t even open a door. That’s the state of the art.

I guess it’s still an open debate, but as for my own feelings, I’m sceptical about some of the claims being made about AI.

Douglas Hofstadter was one of the philosophers who originally called out the AI researchers in 1960s and 1970s for over-promising and under-delivering. He argued that the assertions about AI programs and their progress is a little bit like someone who climbs to the top of the tree, saying he is making steady progress on the way to the moon. But at some point the tree stops. I feel like that statement still holds.

I thought it funny when Elon Musk was quoted last year as saying “We will be like a pet Labrador if we’re lucky” and how close that was to Marvin Minsky’s famous in the 1970s saying “If we are lucky they will treat us like pets.” But you seem to be saying that these kinds of statements aren’t just attention-grabbing or click bait – they are also over-promising what AI can do, albeit in a negative way …

Elon has this wonderful ability to say evocative things like “we are summoning the demon”.

Some people have criticized the media for their reporting of the Future of Life Institute’s activities, but I felt that the Institute may have brought this on themselves to some degree. They talk about the “existential risks” of AI, so it’s no surprise that some of the media picked up on this and jumped immediately to The Terminator. Afterall, what is The Terminator if it’s not an existential threat?

I don’t think that existential threat is a bad motif for people’s concerns, but I also think this is a field that routinely over-promises. It’s true that we have seen significant progress in terms of machines that can see, listen and understand natural language. But cognition reasoning systems are still making baby steps.

That said, I’m supportive of the efforts of Elon Musk and his colleagues at the Future of Life Institute because I do believe that machine autonomy is increasingly becoming a reality in everything from the workplace to weapons, and it’s worth talking about these issues whether autonomous machines are self-aware or not.

As a journalist following the field, you’ve had a unique opportunity to watch a whole new crop of roboticists and AI experts mature. Is this next generation continuing to fuel the polarization between AI and IA, or are the two camps starting to merge?

It’s hard to predict what will become of this current debate. Looking at the issue of technological unemployment in particular, I’ve come to feel that the actual impact of automation technologies on the workforce is a much murkier question than either the press or the science community seems to believe.

Once you start reading the economists, you realize there is a multiplicity of issues going on, including things like tax policy and changing demography, and picking it apart is very difficult. It’s a huge debate, and I’ve come away feeling I know less than when I started.

But I’ve spent a lot of time talking to people working in this field – mostly around Stanford and Berkeley – and it makes me hopeful because there is a generation of young scientists and engineers who are actually exposed to some of the issues we’ve been talking about and are really thinking about them. Ultimately, these machines are being built by humans, so it comes down to individuals having to make decisions about how to design their machines, and their values become really important.

Thank you! It was such a pleasure to read your book and to have a chance to talk to you today.

It was great talking to you – I enjoyed it.

Machines of Loving Grace was released in August 2015, and is available in hardcover, softcover and e-book formats.

If you liked this post, you may also enjoy:

-

New book by John Markoff explores common ground between humans and robots

- Talking Machines: History of machine learning, w. Geoffrey Hinton, Yoshua Bengio, Yann LeCun

- Funding high risk proposals at the National Science Foundation: A brief history

- Passion for utility drove Engelberger’s vision for robotics

- Should cars be fully driverless? No, says MIT engineer and historian David Mindell

- DARPA’s Gill Pratt on Google’s robotics investments

- From pencil and paper to hands-on making, a brief history of MIT’s legendary MechE 2.007

tags: AI, Book, c-Politics-Law-Society, history, history of robotics, John Markoff