Robohub.org

“Drone Art” – an excerpt from The Drone Primer

This is an excerpt from The Drone Primer: A Compendium of the Key Issues, a free, one-stop, handbook addressing the basic and fundamental questions around drones in all their contexts, from foreign theaters of war to domestic civilian use. This basic report covers technology, history, strategy, law, and culture, and includes a portfolio of drone art. It addresses what the authors identified as as a serious problem: the lack of any single, well-written, comprehensive introduction to drones that was not driven by a political, moral or commercial agenda. Written for a general audience, The Drone Primer explains how drones work, their history, how they are used, the concerns that they have raised, their practical benefits, the debate that they have sparked, and the art trend that they have inspired.

Click here to read the full Primer for free.

Chapter 8 – DRONE ART

“The policy discussion is a highly specialized system with its own language and its own elite— almost a priesthood—who understand it and can explain it. By bringing back that analysis, by demystifying it, by looking at how we can explain it better and have clearer discussions around it, I think art has the potential to perform a very important role in policy.” – James Bridle

Over the past few years, artists have responded to the drone in various mediums. Art that treats the drone as its subject, or an art-making tool, has served to interrogate, protest, and promote this technology. This art has been well received by the public and has earned institutional recognition, to the extent we could confidently claim that it is an art trend. The art that makes up this movement is most commonly referred to as drone art.

Because of its cultural resonance, the drone has embedded itself in the popular visual vocabulary. Visions of the drone—usually some kind of variation on the U.S. Predator or Reaper—pop up in graffiti murals, collages, animations, and conceptual art with increasing frequency. Its distinctly sharp, cockpitless form has become a visual motif representing technological advancement, state power, and the spectre of autonomous technology.

In established art practices, we have seen drone art range from straight-served activism— as in the case of Heather Layton and Brian Bailey’s exhibition Home Drone, which asked its American audience to imagine what it would be like to live under drones—to more subtle forms, as Mahwish Chishty’s drones are painted in the aesthetic of Pakistani truck art—to the oblique, like Himanshu Suri’s song “Soup Boys”:

That drone cool, but I hate that drone Chocolate chip cookie dough in a sugar cone Drones in the morning, drones in the night I’m trying to find a pretty drone to take home tonight.

A key feature of the drone art movement is that the drone has served a dual role as both a subject of the artwork and a tool for creating it. In the case of artist and vandal KATSU’s drone graffiti, a drone is the graffiti-making tool. One of the earliest examples of drone art was the Natalie Jeremijenko and the Bureau of Inverse Technology’s BIT Plane project (1995). The team flew a camera-equipped, remote-control plane over Silicon Valley, capturing footage of large tech campuses that, on the ground, were closed to the public. In an interview with the Center for the Study of the Drone, Jeremijenko described the project as an “an exploration into this new territory called ‘information space.” The artistic product was a grainy, black-and-white video containing very little useful information about Silicon Valley, but it was a powerful statement about aerial technology and its surveillant potential.

Tomas van Houtryve’s drone-made aerial photographs of American domestic scenes are similarly bi-layered. On one hand, he is, like Layton and Bailey, experimenting with the idea of hypothetical drone strikes in the U.S. and protesting what he believes is a violent and unjust U.S. policy. On the other hand, his compositions flex the power of the drone, and in doing so point at what he considers to be the worrying implications of unmanned aerial technology. Van Houtryve protests the targeted killing campaign by partially demonstrating what the killing machine can do.

This project diverged from aerial drone art that celebrates the machine for its photographing ability without raising objections or concerns. Drone aerial photography, much of it created by amateurs, is a burgeoning field. While aerial photography has been practiced in various forms since the 19th century, its accessibility and popularity has exploded in recent years. Drone aerial photography was popularized by Raphael “Trappy” Pirker, who in 2010 grabbed U.S. headlines for flying a camera-equipped drone over the Statue of Liberty, the Brooklyn Bridge, and parts of Lower Manhattan.

While Trappy contends that his interest is in flying rather than art, his videos have inspired an aesthetic that disabuses itself of the political discussion and focuses instead on the sheer beauty of the aerial perspective.

Chapter 9 – PORTFOLIO

The Drone Art movement is important because it has contributed a vibrant visual vocabulary to the drone debate. It is also a test case of how different sectors of the art world—from fine gallery art to conceptual virtual art—respond to (and sometimes incorporate) a new technology.

Pakistani artist Mahwish Chishty relays the image of the drone through a classic Pakistani truck art aesthetic; in doing so, she raises questions about how the continuous presence of drones over parts of Pakistan have earned the drone a place in the country’s culture.

The BIT Plane project made use of the drone as a flying tripod, but in doing so also made a statement about the technology itself. Fernando Brizuela’s watercolors create a space of intersection between an old- fashioned, high art practice and a commentary on modern warfare.

James Bridle and Trevor Paglen, two seminal drone artists, meditate on the invisibility of the drone. Paglen takes super-long-range photographs of U.S. military drones flying at high altitude. In the resulting images, the drones often appear as nothing more than dark specks in the wide desert sky.

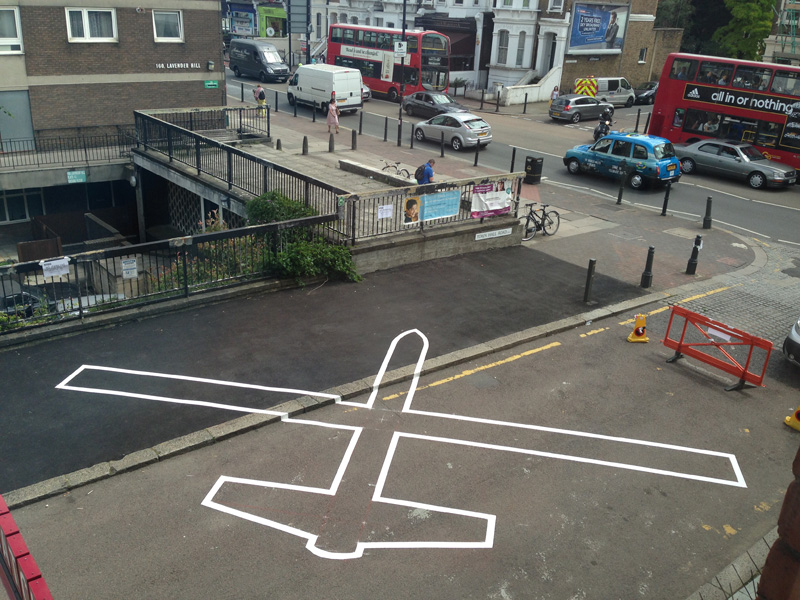

Bridle, on the other hand, traces 1:1 scale outlines of military drones in public spaces–he calls them Drone Shadows. “The Shadows are not really about what the drone looks like,” Bridle told the Center for the Study of the drone. “They’re about the absence of the drone in the contemporary discourse.”

Fernando Brizuela. “drone,” 2013. Watercolor on Paper.

Trevor Paglen, “Untitled (Predators; Indian Springs, NV),” 2010 [Detail]. Credit: Altman Siegel

James Bridle, “Drone Shadow 007: The Lavender Hill Drone” 2014

Mahwish Chishty, “MQ9/1,” 2011. Gauche, tea stain and gold leaf on paper. 8” x 28.5”

tags: Book, c-Arts-Entertainment, cx-Aerial, robohub focus on arts and entertainment