Robohub.org

What’s hot in robotics? Four trends to watch

Four diverse trends are having a big effect on the robotics industry worldwide, and the global media and financial gurus are paying attention to the process.

1. Broad recognition of robotics

There is broad recognition within the business world of the value of robotics and that growing awareness is spreading to the media and financial community. Efficiency, reliability, low spoilage, and higher overall productivity are the real products of advanced automation. And the newer air, land and sea service robots are providing the wow factor. In the last 12 months there have been special sections about robotics in The Economist, The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Time Magazine and many others. And many financial institutions and consulting firms such as McKinsey and Deloitte have produced special reports about the march of advanced manufacturing and its effect on jobs, job types, job creation and employment in general.

There is broad recognition within the business world of the value of robotics and that growing awareness is spreading to the media and financial community. Efficiency, reliability, low spoilage, and higher overall productivity are the real products of advanced automation. And the newer air, land and sea service robots are providing the wow factor. In the last 12 months there have been special sections about robotics in The Economist, The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, Time Magazine and many others. And many financial institutions and consulting firms such as McKinsey and Deloitte have produced special reports about the march of advanced manufacturing and its effect on jobs, job types, job creation and employment in general.

Strategic acquisitions in the robotics arena are rampant and became most visible in 2012 when Amazon acquired Kiva Systems to help bolster their warehousing methods into the future, for $775 million. Since then, 2013, 2014 and 2015 have seen similar big-dollar acquisitions by companies and equity firms. The most recent four are indicative of the range and types of reasoning for these types of strategic acquisitions:

- Ninebot, a Chinese maker of mobile bots similar to the Segways used by police, vacationers and security personnel, bought Segway. This settled their ongoing legal battles and enables Ninebot to acquire Segway’s intellectual property.

- Kuka, a German robot manufacturer and one of the Big Four in the industry, last year bought Swisslog to add mobility to the Kuka product line. Kuka also bought Reis Robotics which had a factory in China. Kuka opened their own factory in Shanghai and thus now has two.

- China South Rail (CSR) acquired UK-based SMD, a provider of underwater robotics technologies and systems. The acquisition is expected to help China obtain core deep-sea robotic technology and equipment, and will also help CSR absorb the mature industry platform and global sales network of SMD, supporting it to enter the global deep-sea market. This will complement CSR’s existing businesses in offshore wind energy, shipyard, marine engineering and drilling and help the Chinese company build an international chain for marine equipment.

- Teradyne spent $350 million to buy up-and-coming Universal Robots, a Danish maker of one-armed safe collaborative robots and the primary competitor to American Rethink Robotics, which, although they get most of the publicity, aren’t doing as well as UR. Teradyne is an electronics manufacturer that, up until now, had no robotic presence except as a user of UR products.

2. The China effect

Global industrial robot sales reached 225,000 units in 2014, 27% more than 2013. About 56,000 were sold in China, a growth of 58% over 2013. Chinese companies made 16,000 of the 56,000 robots sold domestically. To increase the number of domestically made robots, many local governments have provided investment credits and other attractive financial reasons to build in their areas, and the number of vendors has grown from fewer than 100 (of which even fewer were manufacturers; most were integrators and distributors) to almost 500. By the end of 2014, there were about 500+ companies in the sector, with 90% focusing on component manufacturing and integration. China Daily expects the number to increase to 800 by the end of this year, but also that there will be more than 10% manufacturers. Thus China is cultivating their own in-country robotics industry. They’ve set up a robotics association, the CRIA, to help mobilize and promote the new industry and so that they can poll their members and add the results to the annual tabulations made by the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) which, up until 2013, had no resource to robotic activity within China.

Global industrial robot sales reached 225,000 units in 2014, 27% more than 2013. About 56,000 were sold in China, a growth of 58% over 2013. Chinese companies made 16,000 of the 56,000 robots sold domestically. To increase the number of domestically made robots, many local governments have provided investment credits and other attractive financial reasons to build in their areas, and the number of vendors has grown from fewer than 100 (of which even fewer were manufacturers; most were integrators and distributors) to almost 500. By the end of 2014, there were about 500+ companies in the sector, with 90% focusing on component manufacturing and integration. China Daily expects the number to increase to 800 by the end of this year, but also that there will be more than 10% manufacturers. Thus China is cultivating their own in-country robotics industry. They’ve set up a robotics association, the CRIA, to help mobilize and promote the new industry and so that they can poll their members and add the results to the annual tabulations made by the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) which, up until 2013, had no resource to robotic activity within China.

Driven by increasing wages and political incentives, China has been forced to become the largest buyer of industrial robots – and they are putting those robots to use by the thousands. The IFR says that China will have more robots operating in its production plants by 2017 than any other country as it cranks up automation of its car and electronics factories. A race by carmakers to build plants in China along with wage inflation will push the number of industrial robots to more than 428,000 by 2017, the IFR estimates. Still, China lags far behind its more industrialised peers in terms of robot density. According to the IFR, China has just 30 robots per 10,000 workers employed in manufacturing industries, compared with 437 in South Korea, 323 in Japan, 282 in Germany and 152 in the United States. The low density rate is an indicator of continued fast growth to stay competitive and raise the density rate to at least that of the US.

3. Advances in visual perception

Vision-enhanced robotic systems are becomming the top reason for upgrading and deploying vision-enabled robots and a core reason for the steady upward growth of the robotics industry. Amazon just brought the issue to the public and media’s attention with their recent Amazon Picking Challenge, where a variety of teams from academia used varying technologies to robotically pull various consumer items randomly placed in cubbyhole-type shelves … a typical requirement of Amazon in their distribution centers. Being able to determine what and where, in 3D, makes it possible to instruct the robot to safely pick the item(s).

Vision-enhanced robotic systems are becomming the top reason for upgrading and deploying vision-enabled robots and a core reason for the steady upward growth of the robotics industry. Amazon just brought the issue to the public and media’s attention with their recent Amazon Picking Challenge, where a variety of teams from academia used varying technologies to robotically pull various consumer items randomly placed in cubbyhole-type shelves … a typical requirement of Amazon in their distribution centers. Being able to determine what and where, in 3D, makes it possible to instruct the robot to safely pick the item(s).

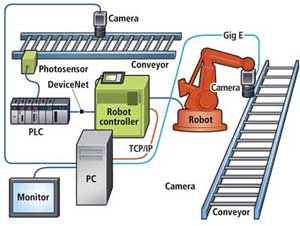

Visual robotic systems are quite different from old-style auto-making robots. These older systems required the part to be worked upon to be in a precise location at a specific time. The robot was blind and programmed to pick and process. Each step of the pick and process was hand programmed and quite detailed. Newer systems that use cameras and software to identify and locate parts are more flexible and enable product movement from step to step to be less rigid and precise; as a consequence, the movement system is less costly.

Artificial intelligence and various AI learning systems have been improving regarding visual perception, and many new companies (such as Universal Robotics and their Neocortex system) are now either offering vision systems that can supplement existing fixed systems or offering mobile manipulators that can find and determine how best to pick and handle all sorts of objects … from plastic-wrapped toys to boxes, cases and skids of materials. Cutting the costs of expensive conveyor and movement systems and replacing them with lower-cost mobile and bin-picking robots is rapidly gaining a big following because of the possible opportunities afforded the manufacturer or warehouse operator. Startups such as Fetch Robotics, RightHand Robotics, Clearpath Robotics and more mature companies such as Adept Technologies and Kuka/Swisslog are ones to watch in this area of mobile manipulators.

4. Human-robot collaboration

A public-private movement to figure out ways to keep labor from being offshored to lower labor cost countries started first in Europe and then followed in the US. It was focused on the small and medium-sized enterprises – factories and shops of less than 500 employees – and was called the SME movement. The concept was that if you empowered shop employees with robotic tools that improved their combined productivity, the SME would become more cost efficient and competitive and therefore not have to move offshore.

A public-private movement to figure out ways to keep labor from being offshored to lower labor cost countries started first in Europe and then followed in the US. It was focused on the small and medium-sized enterprises – factories and shops of less than 500 employees – and was called the SME movement. The concept was that if you empowered shop employees with robotic tools that improved their combined productivity, the SME would become more cost efficient and competitive and therefore not have to move offshore.

Rodney Brooks is an MIT professor emeritus who was one of the founders of iRobot, helped develop the Roomba, mentored the founders of a string of robotic startups, and created Rethink Robotics and the robots Baxter and Sawyer. He is an eloquent spokesman, speaks with a slight Australian accent, and colorfully talks about the need for human and robot collaboration. He makes similar points as the European SME movement but enhances that need by describing how, through the use of co-bots such as Baxter, SME workers become more productive, happier with their jobs, and their overall productivity becomes more cost efficient for the company.

Because the Baxter robot wasn’t up to factory standards when it was launched, the beneficiary of Brooks’ marketing efforts was the competing company, Universal Robots, a Danish startup whose one-armed robots (shown above) had all the attributes that the SME movement and Brooks were espousing. Universal just added a third robot to its product line and now has almost 200 integrators and distributors around the world, and thousands of sold robots at work in SME and larger factories. All three of their robots are identical one-armed robots except in size and carry. The UR3, UR5 and UR10 can carry up to 3, 5 and 10 kilograms of load (6.6, 11 and 22 pounds).

Combined, the SME, Brooks and Universal marketing effort helped make people aware of and understand the benefits of collaborative robotics and the business opportunities that it could bring.

Another and perhaps bigger use of co-bots has been found by automaker BMW, which already has 7,500 robots at work in their factories. BMW has been testing UR robots alongside factory workers who had been tasked with ergonomically-challenging assignments. The robots were quickly trained for those tasks and performed perfectly while freeing up the worker to do even more of what he or she was doing. The results of the tests turned out so well that a BMW spoksman who oversaw the testing, said that it was likely that BMW would soon double or even triple their number of robots by the use of these low-cost, easy-to-program, relatively portable and safe-to-work-alongside robots. Thus one can easily see why Teradyne would pay $350,000,000 for Universal Robots with that kind of endorsement and prospect for the future.

At present, collaborative robots represent 5% of the overall robot market, but have strong growth expectations for the future. ABB, with its recent acquisition of gomTec and their Roberta co-bot (see photo at right) will probably be one of the leaders. Also, Rethink Robotics has improved their systems to be speedier and more precise so that, along with their new one-armed Sawyer robot, they will become a true competitor to the market leader Universal Robots. Because it’s such a booming market, many other companies will soon be offering their products as well. Insiders suggest that collaborative lightweight robots will become the top seller in the industry in about 2 years, selling hundreds of thousands of them and with prices falling to the $10,000 price point.

If you liked this article, you may also be interested in:

- Amazon challenges robotics’ hot topic: Perception

- Danish co-bot maker Universal Robots sells for $350 million

- Consumer and B2B drone making is big business

- Competing robotic warehouse systems

- Swiss to invest almost CHF30 million in digital fabrication research over next 4 years

- Competition heats up for consumer-friendly aerial photography drones

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: c-Business-Finance, cx-Research-Innovation