Robohub.org

3 types of robot singularities and how to avoid them

Wrist singularity. photo: GPA546/youtube

If you are interested in science, “singularity” probably makes you think of a black hole. Black holes are popular in the media right now since the LIGO lab in America proved the existence of gravitational waves. At the center of a black hole, physicists theorize there is a “gravitational singularity”. This means the force of gravity is so big, it goes to infinity. Robotic singularities use exactly the same concept as black holes.

Hang on, let’s back up for a second. What are robotic singularities? And how can they be anything like black holes?

My robot is going crazy

Imagine you want to use your robot to paint a line using a spray painting gun. To paint a perfect line, the robot needs to move at a constant velocity. If the robot changes velocity, some parts of the line will have more paint than others. This won’t look very good. If the robot slows down too much, we’ll get an unsightly blob of paint. Obviously, it’s important that the robot moves along the line at a constant velocity. Robots are precise. Usually they can handle this without a problem. However, if there are any kinematic singularities in the line, the paint job could be ruined.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlGCurgsqg8

This short video demonstrates robot singularities. It shows various examples of the three types of singularity for a 6-axis robot, which we’ll discuss in a moment. The second example of a “wrist singularity” shows the robot trying (and failing) to follow a straight line at a constant velocity. What’s causing this failure? A singularity right in the middle of the line. You could solve this problem in a couple of ways, but first it’s important to understand what’s happening.

Singularities tend to infinity (whether you want them to or not)

Remember I said that the gravity at the center of a black hole “goes to infinity?” This means that the gravitational force gets stronger and stronger the closer you get to the center. At the center of the black hole the gravitational force is theoretically infinite. This might not actually be true (nobody knows), but it’s a property of maths. Mathematics can easily handle the concept of infinity. The real world cannot.

Lots of mathematical equations tend to infinity. As this physicist explains, theoretically you should create a singularity in your bathtub every time you pull the plug. The basic equation for the spiraling water says that the closer you get to the center of the plughole, the faster the water spins. According to the equation, the water should be moving infinitely fast right at the center. In reality that’s not what happens. Physical systems cannot move infinitely fast (as far as we know).

Robot singularities happen because robots are controlled by math (which is okay with infinity), but are made of real, physical moving parts (which isn’t). If an equation commands one robot joint to “rotate 180 degrees at infinite angular velocity”, the robot joint will say “I don’t’ think so!”

What are robot singularities?

Singularities are caused by the inverse kinematics of the robot. When placed at a singularity, there may be an infinite number of ways for the kinematics to achieve the same tip position of the robot. If the optimal solution is not chosen, assuming there is one, the robot joints could be commanded to move in an impossible way. Infinite velocity is not the only type of singularity that causes problems and certain types of singularities can be more problematic than others. Some robots can be put in such a bad position that they need to be turned off, moved, and restarted manually.

The Stewart Platform is a parallel robot which has several difficult singularities. The following video shows one singularity which causes the robot to lose rigidity in two actuators and fall down completely. This happens because the mathematics requires that the (linear) actuator becomes infinitely stiff, which is obviously impossible.

The follow-up video shows how the platform can’t be moved back to the correct position, because the actuator controllers have an infinite gain at the singularity.

The 3 types of robot singularities

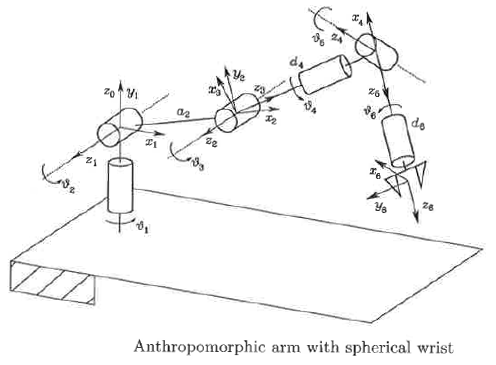

Thankfully, industrial robots are not as problematic as the Stewart Platform. 6-axis industrial robots only suffer from three types of singularities. However, these singularities can still cause havoc.

The American National Standard for Industrial Robots and Robot Systems defines singularities as “a condition caused by the collinear alignment of two or more robot axes resulting in unpredictable robot motion and velocities”. Therefore, the three types of singularities are defined by which joint alignments cause the problem:

- Wrist singularities – These happen when two of the robot’s wrist axes (joints 4 and 6) line up with each other. This can cause these joints to try and spin 180 degrees instantaneously.

- Shoulder singularities – These happen when the center of the robot’s wrist aligns with the axis of joint 1. It causes joints 1 and 4 to try and spin 180 degrees instantaneously. A subset of this is an Alignment Singularity, where the first and last joints of the robot (joints 1 and 6) line up with each other.

- Elbow singularities – These happen when the center of the robot’s wrist lies on the same plane as joints 2 and 3. Elbow singularities look like the robot has “reached too far”, causing the elbow to lock in position. This video shows a good example of an elbow singularity which causes the robot to get stuck.

This video shows a useful simulation of these robot singularities. In the video, the joints are colored red when they are commanded to an infinite velocity, which shows the whole idea pretty clearly.

How to avoid singularities

Manufacturers program their robots so that singularities don’t break the robot. However, in the past this just meant that if one joint was commanded to move too fast, the robot stopped completely with an error message. This was not a very elegant solution.

These days, many robot manufacturers are improving their singularity avoidance. In the video above, the robot had been programmed with a maximum speed for each joint. When the wrist joint was commanded “to infinity”, this caused the software to reduce the velocity of the tip. The robot slowed down when it reached the middle of the line. When it passed the singularity, it was able to continue doing the rest of the line at the correct velocity. The paint job still would have been ruined, but the robot nevertheless functions correctly and doesn’t get stuck.

How programmers avoid singularities

Singularity avoidance has been a developing topic for many years. Various solutions have been proposed and some are starting to make their way into industrial robots. For an introduction to the basics, the ETS Control and Robotics Lab cites a good academic paper which explains the mathematics behind robot singularities and provides examples using an industrial robot.

The more axes that a robot has the more possibilities for singularities. This is because there are more axes which can line up with each other. However extra axes can also reduce the effect of singularities by allowing alternative positions to reach the same point. This paper gives a good introduction on the control of redundant robot arm manipulation, with discussions of how to deal with singularities through programming.

How technicians avoid singularities

Robot technicians have come up with many ingenious ways to avoid singularities over the years. Singularities usually occur when the robot’s links are lined up straight and/or when a joint approaches zero degrees. As a result, technicians started to add small angles to the tooling to reduce the chance that the robot moves into a singularity.

This technique is still a good way to avoid singularities. Mounting a spray painting gun at a very slight angle (5-15 degrees) can sometimes ensure that a robot avoids singularities completely. Not always, but it’s a cheap solution and easy to try.

Finally, another good technique is to move the task into a part of the workspace where there are no singularities. This is not always possible, but can be very effective.

Original blog post: ‘Why Singularities Can Ruin Your Day’

tags: c-Education-DIY, cx-Research-Innovation