Robohub.org

How might drone racing drive innovation?

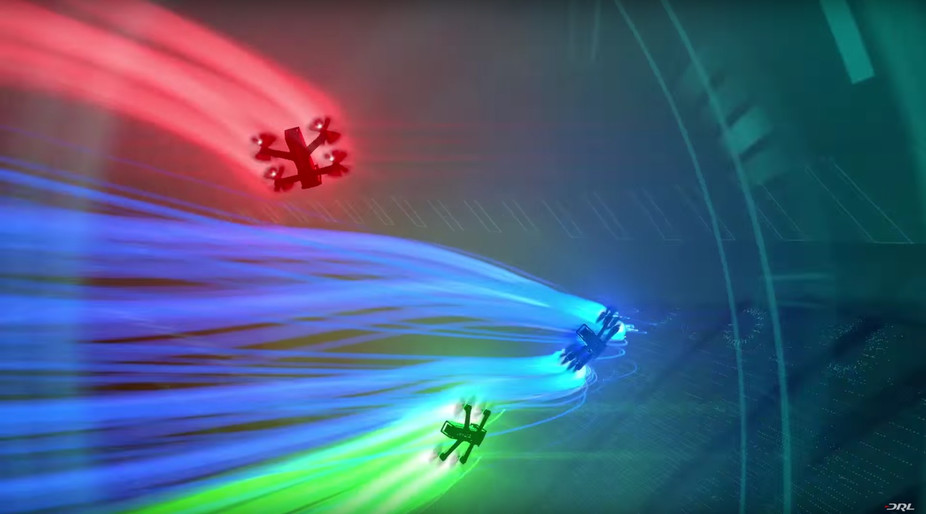

Racing drones in flight. The Drone Racing League, CC BY-ND

Over the past 15 years, drones have progressed from laboratory demonstrations to widely available toys. Technological improvements have brought ever-smaller components required for flight stabilization and control, as well as significant improvements in battery technology. Capabilities once restricted to military vehicles are now found on toys that can be purchased at Wal-Mart.Small cameras and transmitters mounted on a drone even allow real-time video to be sent back to the pilot. For a few hundred dollars, anyone can buy a “first person view” (FPV) system that puts the pilot of a small drone in a virtual cockpit. The result is an immersive experience: Flying an FPV drone is like Luke Skywalker or Princess Leia flying a speeder bike through the forests of Endor.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4wSG3m4VNlo

Perhaps inevitably, hobbyists started racing drones soon after FPV rigs became available. Now several drone racing leagues have begun, both in the U.S. and internationally. If, like auto racing, drone racing becomes a long-lasting sport yielding financial rewards for backers of winning teams, might technologies developed in the new sport of drone racing find their way into commercial and consumer products?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0gYkZGOTdM0

An example from history

Auto racing has a long history of developing and demonstrating new technologies that find their way into passenger cars, buses and trucks. Formula 1 racing teams developed many innovations that are now standard in commercially available vehicles.

These include disk brakes, tire design and materials, electronic engine control and monitoring systems, the sequential gearbox and paddle shifters, active suspension systems and traction control (so successful that both were banned from Formula 1 competition), and automotive use of composite materials such as carbon fiber reinforced plastics.

Starting with the basics

Aerodynamically, the multi-rotor drones that are used for racing are not sophisticated: A racing drone is essentially a brick (the battery and flight electronics) with four rotors attached. A rectangular block has a drag coefficient of roughly 1, while a carefully streamlined body with about the same proportions has a drag coefficient of about 0.05. Reducing the drag force means a drone needs less power to fly at high speed. That in turn allows a smaller battery to be carried, which means lighter weight and greater maneuverability.

This is a case where technologies from aircraft and helicopter aerodynamics will find their way to the smaller vehicles. Commercial drone manufacturers have begun working on aerodynamic optimization, using techniques such as wind tunnel testing and computational fluid dynamics originally developed for analysis and design of full-scale aircraft and helicopters.

That may be able to enable longer flight times. If so, it would give drone operators more time to take money-making photos and video in flight. It could also boost drones’ ability to assist missions such as searching for lost hikers. If drone racing becomes a billion-dollar per year sport – like auto racing – teams will deploy well-funded research labs to eke out every last bit of performance. That additional incentive – and spending – could be poured into racing advances that will push drone technology farther and faster than might otherwise be the case.

Organized competition isn’t the only way to innovate, of course: Drone development has accelerated even without it. Today, the cheapest drones cost under US$50, though they can fly only indoors and have very limited flight capabilities. Hobby drones costing hundreds of dollars can perform stunning aerobatic feats in the hands of a skilled pilot. Drones capable of autonomous flight are also available, though they cost thousands of dollars and are used for more specialized purposes like scientific research, cinematography, law enforcement, and search and rescue.

Advancing control and awareness

The drones used in racing (and indeed, all current multi-rotor drones) contain hardware and software to improve stability. This is essentially a low-level autopilot responsible for “balancing” the vehicle. The human pilot controls the vehicle’s front/back and left/right tilt angles and the magnitude of the total thrust, as well as how fast the vehicle turns and changes direction.

There is no reason why this must be done via control sticks, as is currently common: Pilots could use a smartphone to control the drone instead. There is, in fact, no reason why drone control needs to be done using a physical interface: recently the University of Florida hosted a (very basic) drone race using brain-machine interfaces to control the drones.

Aside from flight control, situation awareness is a key problem in drone operations. It is all too easy to crash a remotely operated vehicle into a pillar on the left when the cameras are all pointed forwards. In addition, the pilot of the lead drone in a race has no way of knowing where the competitors are: They could all be a long way behind, or one could be in a position to pass.

Solving this problem could have payoffs for other telepresence robotics operations, such as remotely operated underwater vehicles and even planetary rovers. Vision systems consisting of several cameras and a computer to stitch together the different views could help, or a haptic system could vibrate to alert a pilot to the presence of a drone or other obstacle nearby. Those sorts of technologies to improve the pilot’s awareness during a race could also be used to assist a remote-control robot pilot operating a vehicle at an oil drilling platform or near a hydrothermal vent in the deep ocean.

This is of course still very speculative: Drone racing is a sport still in its infancy. It is not yet clear whether it will become a massively popular sport. If it does, we could see very exciting advances coming from drone racing into both the toys that we fly in our living rooms and parks and into the drones used by professional videographers, engineers and scientists.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

tags: c-Aerial, drone racing, UAV