Robohub.org

Robotic science may (or may not) help us keep up with the death of bees

Beginning in 2006 beekeepers became aware that their honeybee populations were dying off at increasingly rapid rates. Scientists are also concerned about the dwindling populations of monarch butterflies. Researchers have been scrambling to come up with explanations and an effective strategy to save both insects or replicate their pollination functions in agriculture.

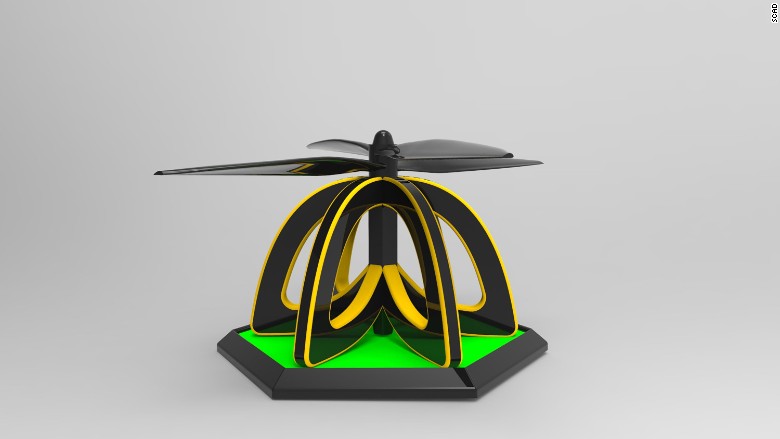

Although the Plan Bee drones pictured above are just one SCAD (Savannah College of Art and Design) student’s concept for how a swarm of drones could handle pollinating an indoor crop, scientists are considering different options for dealing with the crisis, using modern technology to replace living bees with robotic ones.Researchers from the Wyss Institute and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Harvard introduced the first RoboBees in 2013, and other scientists around the world have been researching and designing their solutions ever since.

Honeybees pollinate almost a third of all the food we consume and, in the U.S., account for more than $15 billion worth of crops every year. Apples, berries, cucumbers and almonds rely on bees for their pollination. Butterflies also pollinate, but less efficiently than bees and mostly they pollinate wildflowers.

The National Academy of Sciences said:

“Honey bees enable the production of no fewer than 90 commercially grown crops as part of the large, commercial, beekeeping industry that leases honey bee colonies for pollination services in the United States.

Although overall honey bee colony numbers in recent years have remained relatively stable and sufficient to meet commercial pollination needs, this has come at a cost to beekeepers who must work harder to counter increasing colony mortality rates.”

Florida and California have been hit especially hard by decreasing bee colony populations. In 2006, California produced nearly twice as much honey as the next state. But in 2011, California’s honey production fell by nearly half. The recent severe drought in California has become an additional factor driving both its honey yield and bee numbers down as less rain means less flowers available to pollinate.

In the U.S., the Obama Administration created a task force which developed The National Pollinator Health Strategy plan to:

- Restore honey bee colony health to sustainable levels by 2025.

- Increase Eastern monarch butterfly populations to 225 million butterflies by year 2020.

- Restore or enhance seven million acres of land for pollinators over the next five years.

For this story, I wrote to the EPA specialist for bee pollination asking whether funding was continuing under the Trump Administration or whether the program itself was to be continued. No answer.

Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology scientists have invented a drone that transports pollen between flowers using horsehair coated in a special sticky gel. And scientists at the Universities of Sheffield and Sussex (UK) are attempting to produce the first accurate model of a honeybee brain, particularly those portions of the brain that enable vision and smell. Then they intend to create a flying robot able to sense and act as autonomously as a bee.

Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology scientists have invented a drone that transports pollen between flowers using horsehair coated in a special sticky gel. And scientists at the Universities of Sheffield and Sussex (UK) are attempting to produce the first accurate model of a honeybee brain, particularly those portions of the brain that enable vision and smell. Then they intend to create a flying robot able to sense and act as autonomously as a bee.

Bottom Line:

As novel and technologically interesting as these inventions may be, the metrics will need to be near to the present costs of pollination. Or, as biologist Dave Goulson said to a Popular Science reporter, “Even if bee bots are really cool, there are lots of things we can do to protect bees instead of replacing them with robots.”

Saul Cunningham, of the Australian National University, confirmed that sentiment by showing that today’s concepts are far from being economically feasible:

“If you think about the almond industry, for example, you have orchards that stretch for kilometres and each individual tree can support 50,000 flowers,” he says. “So the scale on which you would have to operate your robotic pollinators is mind-boggling.”

“Several more financially viable strategies for tackling the bee decline are currently being pursued including better management of bees through the use of fewer pesticides, breeding crop varieties that can self-pollinate instead of relying on cross-pollination, and the use of machines to spray pollen over crops.”

tags: c-Research-Innovation, Wyss Institute