Robohub.org

Fish fins are teaching us the secret to flexible robots and new shape-changing materials

By Francois Barthelat

The big idea

Segmented hinges in the long, thin bones of fish fins are critical to the incredible mechanical properties of fins, and this design could inspire improved underwater propulsion systems, new robotic materials and even new aircraft designs.

Francois Barthelat, CC BY-ND

Fish fins are not simple membranes that fish flap right and left for propulsion. They probably represent one of the most elegant ways to interact with water. Fins are flexible enough to morph into a wide variety of shapes, yet they are stiff enough to push water without collapsing.

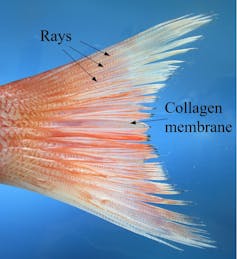

The secret is in the structure: Most fish have rays – long, bony spikes that stiffen the thin membranes of collagen that make up their fins. Each of these rays is made of two stiff rows of small bone segments surrounding a softer inner layer. Biologists have long known that fish can change the shape of their fins using muscles and tendons that push or pull on the base of each ray, but very little research has been done looking specifically at the mechanical benefits of the segmented structure.

A pufferfish uses its small but efficient fins to swim against, and maneuver in, a strong current.

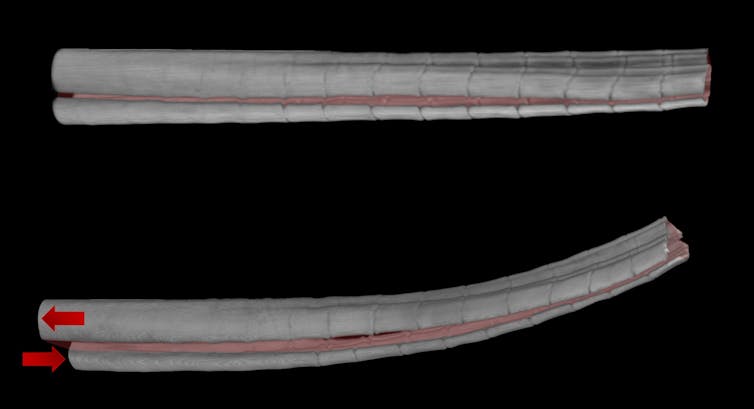

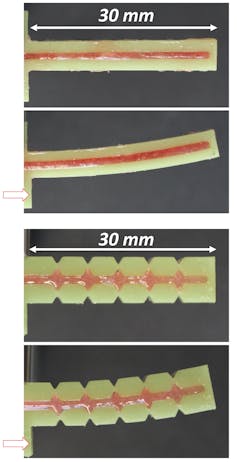

To study the mechanical properties of segmented rays, my colleagues and I used theoretical models and 3D-printed fins to compare segmented rays with rays made of a non-segmented flexible material.

We showed that the numerous small, bony segments act as hinge points, making it easy to flex the two bony rows in the ray side to side. This flexibility allows the muscles and tendons at the base of rays to morph a fin using minimal amounts of force. Meanwhile, the hinge design makes it hard to deform the ray along its length. This prevents fins from collapsing when they are subjected to the pressure of water during swimming. In our 3D-printed rays, the segmented designs were four times easier to morph than continuous designs while maintaining the same stiffness.

Francois Barthelat, CC BY-ND

Why it matters

Morphing materials – materials whose shape can be changed – come in two varieties. Some are very flexible – like hydrogels – but these materials collapse easily when you subject them to external forces. Morphing materials can also be very stiff – like some aerospace composites – but it takes a lot of force to make small changes in their shape.

Francois Barthelat, CC BY-ND

The segmented structure design of fish fins overcomes this functional trade-off by being highly flexible as well as strong. Materials based on this design could be used in underwater propulsion and improve the agility and speed of fish-inspired submarines. They could also be incredibly valuable in soft robotics and allow tools to change into a wide variety of shapes while still being able to grasp objects with a lot of force. Segmented ray designs could even benefit the aerospace field. Morphing wings that could radically change their geometry, yet carry large aerodynamic forces, could revolutionize the way aircraft take off, maneuver and land.

What still isn’t known

While this research goes a long way in explaining how fish fins work, the mechanics at play when fish fins are bent far from their normal positions are still a bit of a mystery. Collagen tends to get stiffer the more deformed it gets, and my colleagues and I suspect that this stiffening response – together with how collagen fibers are oriented within fish fins – improves the mechanical performance of the fins when they are highly deformed.

What’s next

I am fascinated by the biomechanics of natural fish fins, but my ultimate goal is to develop new materials and devices that are inspired by their mechanical properties. My colleagues and I are currently developing proof-of-concept materials that we hope will convince a broader range of engineers in academia and the private sector that fish fin-inspired designs can provide improved performance for a variety of applications.

Francois Barthelat does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article appeared in The Conversation.

tags: bio-inspired, c-Research-Innovation