Robohub.org

New quadrocopter video points to a future for flying machines in entertainment

We’ve seen robots on stage before: Humanoids have been featured in theater productions in Switzerland, Austria, and Japan, and industrial robots have played parts in dance performances and other staged events. Flying robots have also played a theatrical role, for example in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Texas A&M, a dance set to a Schubert piano trio at MIT, as well as in advertising. Some robots have even gone pro: Robothespian was designed for acting and is rented out for performances.

But the dance between human and machine has never looked quite like this .

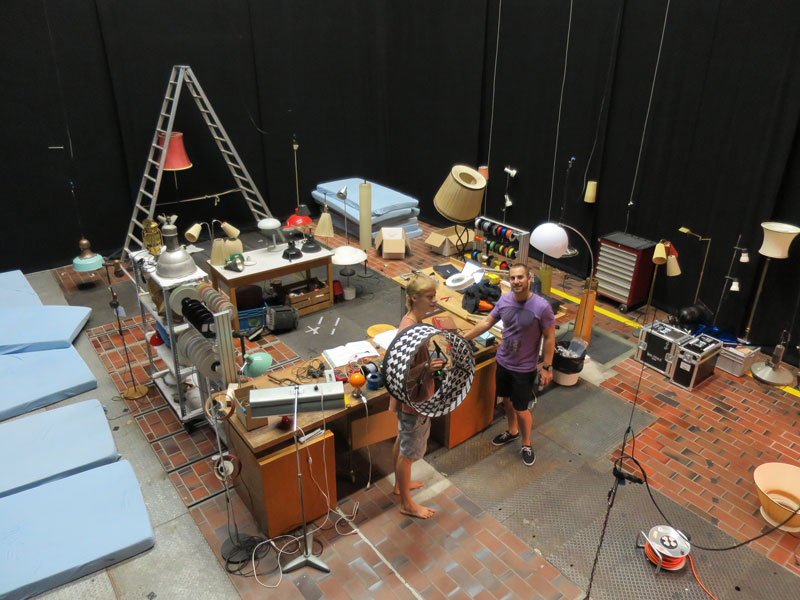

The film’s main plot is straight-forward: Lamps in a repair shop magically come alive, rising from their stands to sneak up on an unsuspecting repairman. As the magic unfolds, and the repairman discovers that the everyday objects of his trade have become animated and full of character, viewers become witness to the evolving dance between man and technology.

Everyone on the team, including myself, was impressed by how well the film captures the stunning, at times hypnotic visuals of the flying lampshades. Everything you see is real — no CGI, wires, or speed-ups/slow-downs were used in the film.

So how did the lampshades come alive?

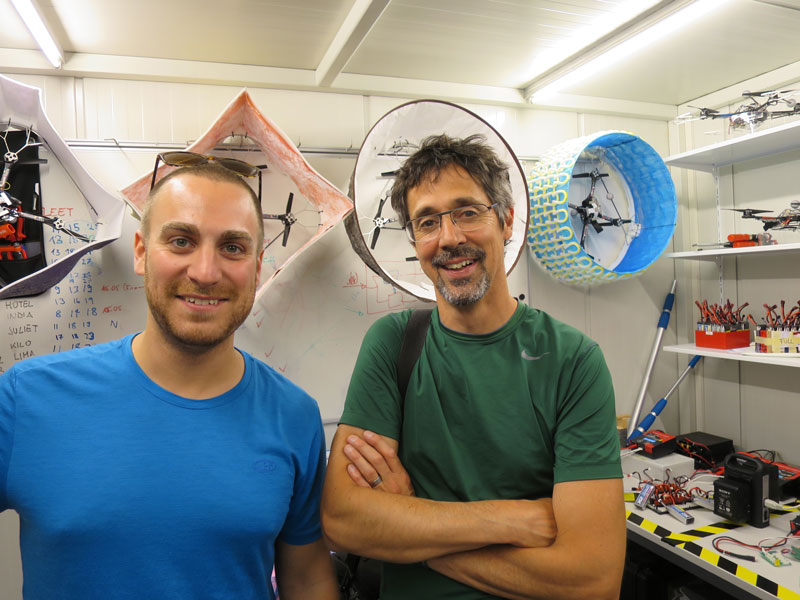

This short film, titled “Sparked”, was produced in collaboration between researchers at ETH Zurich’s Flying Machine Arena, their spin-off company Verity Studios, and entertainment company Cirque du Soleil; in other words, it’s quadrocopter magic that makes the lampshades fly.

The film marks a step change from previous work by ETH Zurich’s Flying Machine Arena team, catalyzed by their new spin-off company Verity Studios, which also gets credit for designing the quadrocopters’ choreography. Here, in spite of their computer-controlled precision flights, the flying machines become robot actors that are individuals with their own personalities: Pomponette, with her tassels bustling in the propellers’ airflow; the Medusa with its bizarre tentacles waving in the wind; the Runt, sleek and fast but still glowing and twitching from the electric shock. And Lady Purple, absent from most of the film because of her intractable aerodynamics.

Flying machines up, close, and personal

One of the most striking aspects of this film shoot was watching our actor, Nicolas Leresche, interact with the flying machines. Much of this interaction was captured on camera — and you can see the results in the film, in particular the moment of ‘first contact’ — but, for me, it was what happened off-camera that was most revealing.

Naively unjaded by their joys and dangers, this was Nicolas’ first experience with quadrocopters. As he began interacting with them, tentatively at first, and then — in a matter of seconds — more confidently, even playfully, it became crystal clear that I was not merely observing a human using a robotic tool.

As the quadrocopter’s onboard controller pushed back against Nicolas’ hand, immediately reacting to match his actions, it became apparent that the two interacted in a way we don’t usually get to interact with technology. The interaction here was physical and dynamic, and clearly intuitive for Nicolas. There was no noticeable learning curve, no need for manuals or explanations.

But what was most striking about this interaction was the result. Within seconds, Nicolas had established a deep, almost animate connection with the flying robot actors. As their dance developed, driven by the autonomous machines’ choreography and Nicolas’ script, and became ever more fluid and natural, it became clear that what we were witnessing was a relationship in its making; one of mutual respect and, at the same time, confidence and trust. And once there was trust, magic happened.

In his own words:

Actors think that they are the ones who make objects move. I think that, on the contrary, it’s the objects that make us move. In the case of drones, even more so! They are companions (in an etymological sense), confrères, brothers.

Within hours the entire film crew had become comfortable with the flying machines hovering nearby or brushing past them as they swooshed through the air. On one occasion, a mis-timed dolly motion led to a flying machine hovering just centimeters above the camera man, who continued with his work unfazed. On another occasion, when Nicolas missed his cue, he bumped into one of the flying machines. But they just jostled past each other and continued on with their choreography as if nothing exceptional had happened. On yet another occasion, a drone collided with the moving camera without disturbance.

The only damage during the entire two-day shoot was a single broken lamp, knocked over by one of the quadrocopters’ airflow.

Safety

I have no doubt that this level of confidence and comfort with the technology can in no small part be attributed to the system’s reliability. In spite of the packed shooting schedule (a total of 40 shots over two days) and the high complexity of the project (for example, designing lighting conditions using more than 60 light sources including some moving through space), production went smoothly, and importantly for the quadrocopter team, the flying machines did not add any significant delay. Battery swaps and on-the-spot changes to the choreography were efficient and quick, never exceeding a few minutes. Kudos to the excellent film team from who’s mcqueen for brilliantly doing their part to keep the production on schedule.

Collaboration

One aspect that made this project particularly enjoyable was the collaboration with creatives at Cirque du Soleil. From the start there was a lot of excitement about the potential of this technology for entertainment not just at ETH and Verity Studios here in Zurich but also at Cirque in Montreal. Everyone shared the view that the flying machines could be used to amaze audiences and to tell wonderful stories. What ensued was a collaborative, iterative creation process that culminated in a script and a set design that were imaginative to Cirque du Soleil standards, while exhibiting the abilities of the quadrocopters in their full splendor.

As it turned out, figuring out what is easy and what is difficult to achieve with autonomous quadrocopters can be quite counter-intuitive. Having researchers and creatives on both sides collaborate on the key creative elements of the story from the early phases of the project therefore proved invaluable to its success.

Next steps

Why go to all this trouble? We’ve all seen the amazing things CGI can do on film. I love films and movies, how they can condense experience and add life to our most impossible dreams. But nothing compares to the real experience of getting up, close, and personal with robot actors yourself.

What’s next? Our audiences over the past years have had more ideas than we can count. At this point, only one thing’s for sure: They all want to see more flying robot actors.

Some more snapshots from the film shoot below for your viewing pleasure:

All images credited to the “Sparked” team. Markus Waibel is a former member of ETH Zurich, a co-founder of Verity Studios, and one of the contributors to “Sparked”.

tags: Algorithm Controls, c-Arts-Entertainment, Cirque du Soleil, cx-Aerial, ETH Zurich, film, human-robot interaction, opinion, robohub focus on arts and entertainment, Verity Studios