Robohub.org

Technical challenges in machine ethics

An Air Force airman at the control module of an MQ-9 Reaper. Credit: John Bainter/USAF

Machine ethics offers an alternative solution for artificial intelligence (AI) safety governance. In order to mitigate risks in human-robot interactions, robots will have to comply with humanity’s ethical and legal norms, once they’ve merged into our daily life with highly autonomous capability. In terms of technical challenges, there are still many open questions in machine ethics. For example, what is deontic logic and how can it be used for improving AI safety? How do we fashion the knowledge representation for ethical robots? What about the adaptiveness of the ethical governance? These are all significant questions for us to investigate.

In this interview, we invite Prof. Ronald C. Arkin to share his insights on robot ethics, with a focus on its technical aspects.

Date: February 1st 2017

Interviewee: Prof. Ronald C. Arkin, Regents’ Professor and Associate Dean in the College of Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Executive Committee Member of IEEE Global Initiative for Ethical Considerations in Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems

Interviewer: Dr. Yueh-Hsuan Weng, Co-founder of ROBOLAW.ASIA and Fellow at CLAST AI & Law Research Committee (Beijing) and Tech and Law Center (Milan).

Ron Arkin

Q1 WENG: Thank you for agreeing to an interview with us. Can you tell us a little about your background?

ARKIN: I have been a roboticist for 35 years, so it’s hard to tell [only] a little, but I will do my best. Currently I am a Regents’ Professor and Associate Dean in the College of Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology. I got my Ph.D. from the University of Massachusetts in 1987, and have been working on robotics since that time. I actually have degrees in chemistry as well—a bachelor’s and a master’s in organic chemistry. So, I have a rather diverse background and followed a non-traditional path compared to most computer scientists.

Q2 WENG: What is your definition of “Ethical Robots”?

ARKIN: That’s an interesting question! I have been asked that one before. I would say an ethical robot is a robotic system that is able to comply with the ethical and social norms of human beings—in some cases in accordance with international law, in other cases in accordance with national or local law. In addition, also being able to comport with humans in a natural manner, obey, and adhere to the same principles as an ethical person.

Q3 WENG: Could you please tell us why you are particularly interested in “Embedded Ethics”? Why is this concept so important?

ARKIN: That’s why you need to read the preface of my book [Governing Lethal Behaviour in Autonomous Robots]. It’s a rather long story. But let me try to give you a short version. Again, it dates back to a meeting—the first international symposium in Roboethics in 2004—where I was exposed to international conventions, e.g., the Geneva convention. It also led me to understand the Vatican’s position on how they viewed appropriate ethical interactions. Perhaps even more important than that one experience was the fact that we roboticists that have been in the field for some time finally started to have success, and we were seeing our technology move out of the laboratory community and into the real world. As such, it wasn’t hard to see how this could go in a variety of different directions.

Some robotics technology could benefit humanity, some not so much. At that point, one has to ask, “who is responsible for this?” So I assumed that, in part, it was myself. I believe that I have to take the responsibility for the technology that I helped to create. The issue is that we, as roboticists, had actually succeeded in many ways in terms of creating technology that we only envisioned when we first started that is going to have potentially profound impact on our society and the world as a whole. As such, we should be proactive in the ways in which we move forward [in order] to get a better understanding of the consequences of the work, and the social implications of the technology we are designing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jOJwkvihYtc

Q4 WENG: The IEEE Global Initiative for Ethical Considerations in Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Systems has published their report “Ethically Aligned Design” in December 2016. As a member of the IEEE Global Initiative, could you please tell us about your role?

ARKIN: I serve a variety of roles. First, I am on the executive committee of that particular initiative, so I work at a high-level with about 30 other people or so. We have committees that large. I also co-chair the committee in Affective Computing. Joanna Bryson is my co-chair on that.

Affective Computing is concerned with the issues surrounding the illusion of emotions we can potentially create in these artifacts, and the ways human beings can bond to them. We are exploring a variety of different things, including robot intimacy, or the notion of applying robotic nudges and moving people in certain directions subtly, and in so doing to change the way people act and behave using these technologies, while trying to understand what may or may not be appropriate guidelines based on ethical considerations.

It’s about 15-20 people in that committee. We are one of the newer committees and we only have a couple of pages in the initial design report. But actually, in the June meeting in Austin, for the next release of the document 2.0, we will have as much as the other committees do. Finally, I am also a member of the humanitarian committee. I think it is called economic and humanitarian. I don’t know the exact title, but I am interested in the humanitarian side, and potential uses of robotics for humanitarian applications.

Q5 WENG: What is “Deontic Logic”? Why does it matter to machine ethics?

ARKIN: It may or may not matter. It’s just one approach to a particular problem. Deontic logic is a logic of prohibitions, obligations and permissions. It is one type of framework that is more transparent in order to get a better understanding of the way in which systems operate in the real world. Then it explains its reasoning to a human being, as compared to say deep learning or other forms of neural networks which may indeed provide good results but provide no explanatory capability to humans after the decision has been made.

The notion of prohibitions basically tells the robot some things it cannot do. The notion of permissions describe the things it is potentially allowed to do. And the notion of obligations says things that the robot must do under specific circumstances. It provides a nice framework of being able to explore morality. Others have already explored this, like Bringsjord at RPI who has applied deontic logic in this framework. We are certainly not the first in that particular space. Much of the work we have done has dealt with first-order predicate logic as a basis. It doesn’t have to be deep because it is so explicit in many cases.

Q6 WENG: Your hybrid embedded ethics framework aims for governing lethal behavior of military robots. Can we apply the same technical framework to service robots? For example, personal care robots might have some non-lethal, but still risky autonomous behaviors that need to be regulated by machine ethics.

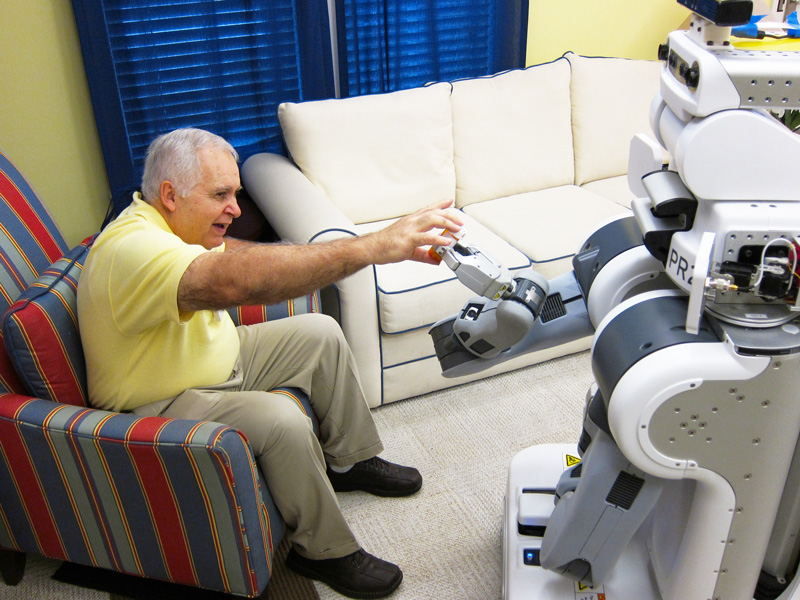

ARKIN: I believe so. Indeed the whole point of the architecture is trying to design the systems to make them generalizable and not ad hoc for particular sets of circumstances. We have yet to look at service robotics in a traditional sense, but we have already developed something we refer to as the intervening Ethical Governor, which we are using for health care applications—particularly for assisting the management of two human beings in a particular relationship, like a patient and their care giver.

A robot hands a medication bottle to a person. Photo credit: Keith Bujak. Source: Georgia Tech News Center

We are doing work for the National Science Foundation, joint with Tufts University, looking at how in early stage Parkinson’s there is a condition called the facial masking. The loss of muscle movements in the face of the patient can produce stigmatization, and the patient-care giver relationship deteriorates due to the loss of non-verbal communication. We just had a paper accepted at ICRA describing the architecture that we have and how it has been modified from the military version. We generalized it from the military constraint-based version to a rule-based version.

But also, instead of using the international humanitarian law, we are using occupational therapy guides as a basis for generating the responses when two human beings in the relationship step outside of acceptable bounds. So the acceptable bounds now are not defined by international humanitarian law, but they are defined by occupational therapy—such as when a patient or a care giver start to yell at each other, or one starts to leave the room. The hard part is recognizing when dignity is being abridged, particularly in the patient. So we model the moral emotions of empathy, shame and embarrassment. We tried to ensure that the empathy level in the care giver remains within acceptable bounds and that the patient shame and embarrassment doesn’t rise to unacceptable levels. So the intervening Ethical Governor intervenes when a really inappropriate event occurs. It then provides strong corrective action by the robot to encourage people to get along better. The moral adaptor component which we used in the ethical architecture—initially with the guilt model—has now been extended to other moral emotions like shame, embarrassment, guilt and empathy [in order to] try and provide more subtle non-verbal queues [to help the] robot steer the relationship in the correct way before it get out of hand.

Q7 WENG: Regarding your research on machine ethics, what kind of indicators you use to evaluate the final outputs of your project?

ARKIN: In the first one, we were designing a prototype to prove the concept of the architecture. We never make the claim that this is the best way to do it. It is just one way to do it. Then we demonstrate that particular capability through the use of simulations and other aspects. The system was not intended to be fielded, but hopefully others could take those core ideas and potentially put them to use in the real world if they so choose. For the intervening governor, we’re running human subject tests right now—not with Parkinson’s patients yet, but with the elderly population, 50 or older. We’re trying to get a better understanding of the correct sets of rules, and to correct the interventions in a normative fashion, so we can ultimately move on in the final year of the grant to work with actual Parkinson’s patients. Again, using standard HRI technics, such as recording the kinds of reactions they have and parsing the data from the sessions and using pre- and post- evaluation questionnaires.

Q8 WENG: Let’s talk about your proposed machine ethics framework. You had mentioned that it includes four main parts: (1) Ethical Governor (2) Ethical Behavior Control (3) Ethical Adaptor (4) Responsibility Advisor. First of all, what is the major difference between Ethical Governor and Ethical Behavior Control? Is it the difference between deliberative and reactive control, or something else?

ARKIN: The Ethical Governor is basically a standalone component to the architecture which is a bolt on component at the end of the existing system. In the case of military scenario: asking for permission—should it fire or not. This is an intervening stage which either grants or denies permission through the validation of permission-to-fire variable. So it is straightforward thing to be able to do. The Behavior Ethical Control is a different kind of thing as it works purely with the reactive component. What it tries to do is, for each of the individual behaviors themselves, to respond whether or not to engage a target. This is prior to dealing with the Ethical Governor making the decision; trying to make the decision correctly before it gets to the Ethical Governor, where individual behaviors are given ethical guidelines to try and ensure that the behavior is correct itself. Each of the behaviors is provided with appropriate ethical constraints. So the difference is: one is located within the reactive component in each of the individual behaviors that makes the activity of the architecture, and the Ethical Governor is at the end of the architectural chain.

Q9 WENG: What is the importance of Ethical Adaptor? What kinds of machine learning skill that you chose to improve its adaptiveness?

ARKIN: Machine learning is something we haven’t generally explored in this particular context. Especially the military context, we kind of engineer out the adaptiveness and machine learning for fear that the robot would be granted the authority to start to generalize the targets in the field, which we feel is inappropriate. Learning after action is okay. but that’s a different story. The importance of the Ethical Adaptor, and its cognitive models of guilt that we use, is the fact that even the actions the agent takes may inadvertently end up unethical. This is referred to as a “moral luck”. It could be good luck or bad luck. But if it is bad luck, you want to be able to ensure proactively that the bad action doesn’t occur again. That’s actually the functions of cognitive guilt for people as well to reduce the likelihood of reoccurrence of a behavior that resulted in bad actions. By giving this to a robot we hope that if it makes a mistake it will not repeat it. The probability of that behavior reoccurring would be reduced.

The best example is the case of battle damage assessment for a military scenario. For example, if a robot does its assessment and it looks like a released weapon wouldn’t create too much collateral damage, within acceptable limits, then it will release the weapon. But after it does it, the battle damage action is actually more severe then, it initially appeared to be. Under those circumstances, we want the robot in the field to reduce the probability of releasing the weapon again under similar circumstances. That’s, in essence, the analogue of guilt we use, and eventually, it will get to the point that the robot will not engage targets at all. Again, the software is updated to make sure the use is consistent with Geneva convention.

Q10 WENG: The Laws of War (LOW) and Rules of Engagement (ROE) are written in the form of natural language. How did you transfer these norms into machine readable formats?

ARKIN: It’s important to keep it in mind that we do not try and capture all the Rules of Engagement and all the Laws of War. We always advocate that the system should be used in very narrow circumstances and very narrow situations, such as building clearing operations or counter-sniper operations. It’s impossible to capture all human morality and all the Laws of War at this particular point of time. So, the question is what are the relevant Laws of War and Rules of Engagement for these particular narrow situations that the robot will find itself in.

Let’s take a room clearing operation. We try and do this using these constraint-based approaches. The Laws of War basically say that if you see a civilian, you should not shoot them; if you see a surrendered person, you should not shoot them. For aerial vehicles, if you are outside the kill zone (this is the simulations we did) which is designated by the Rules of Engagement, you cannot fire your weapon—explain simply why you cannot do that. If you release the weapon a toward a legitimate target but it would result in damage of cultural property, like a mosque or church or some similar circumstance, that is illegal as well. You are forbidden from doing those sort of things.

So, the initial work we did was more for aerial circumstances. We also computed the collateral damage using a battle damage assessment strategy to determine whether if it is within acceptable limits for a particular target and to restrain the weapon for proportionality. To be able to do this you have to be able to understand the military necessity of the target, which is assigned by a human being. You have to be able to understand the proportionality of the weapon. In other words: Which weapon is sufficient to take out the target but to do no more damage of the surroundings than is absolutely necessary? You have to ensure that you don’t destroy cultural property as well. Basically, adhere to all necessary principles, such as discrimination which is to be able to tell apart combatants and non-combatants. We also state we should restrict the use of these particular systems for high-intensity combat operations, or inter-state warfare, and not the kind of circumstances you find in modern counter- insurgency operations. They should be used with great care and great caution in very narrow circumstances where the predictability of their performance is far more likely to be good.

Q11 WENG: Why did you choose case-based reasoning (CBR) but not rule-based reasoning (RBR) when you designed Responsibility Advisor?

ARKIN: Historically we used case-based reasoning a lot for a variety of different reasons. Part of the reason is to gain information from previous experts. One of the examples in the past was to work with snipers in the laboratory. We can work with experts. It can be legal experts, it can be medical experts, it can be military experts. Again, the primary reason is to be able to readily use the experience of warfighters to guide us in operations.

Q12 WENG: Finally, your proposal “Governing Lethal Behavior: Embedding Ethics in a Hybrid Deliberative/Reactive Robot Architecture” was published in 2007. There have been great technological improvements in artificial intelligence in the past decade. Are there any recent updates from your robot ethics research, or anything that you want to share with us?

ARKIN: The project ended around 2010, so there is additional information. As I say, I would encourage those who are really interested to take a look at the book entitled “Governing Lethal Behavior in Autonomous Robots” . That represents the final statement and outcome for that particular project and includes the significant technical details describing that work. Recent advances include the application in other domains, such as the caregiver-patient relationship [discussed above] using the same underlying principles, including both the Moral Adaptor and Ethical Governor in a slightly different. If we were successful, it may also be useful for assisting other human-human relationships, such as a parent and a teenager who may be at odds with one another or even in marriage consulting. We hope to use robots for the benefit of mankind, whether it’s to make sure that warfare is conducted within internationally agreed upon laws, or whether it’s to ensure that people behave appropriately toward each other

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy:

- How do we regulate robo-morality?

- One being for two origins: A new perspective on roboethics

- Considering robot care, ethics & future tech at #ERW2016 European Robotics Week

- On the ethics of research in robotics, with Raja Chatila

- A European perspective on robot law: Interview with Mady Delvaux-Stehres

- Open Roboethics initiative delivers statement to United Nations CCW

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: AI, Algorithm AI-Cognition, Algorithm Controls, Artificial Intelligence, c-Politics-Law-Society, cx-Health-Medicine, cx-Military-Defense, human-robot interaction, interview, Laws, machine learning, military, policy, roboethics