Robohub.org

Using MATLAB for hardware-in-the-loop prototyping #1 : Message passing systems

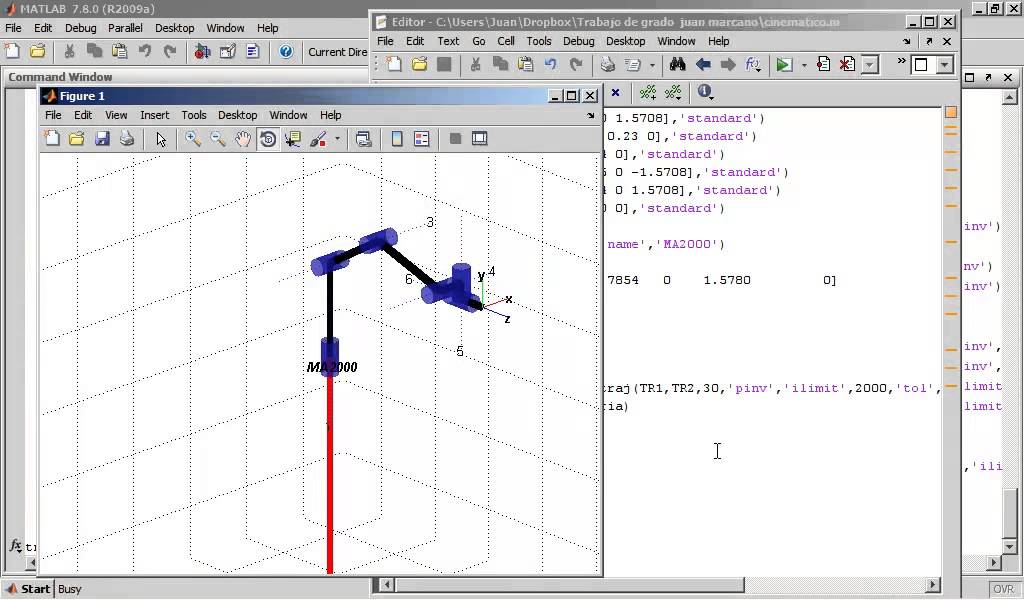

MATLAB© is a programming language and environment designed for scientific computing. It is one of the best languages for developing robot control algorithms and is widely used in the research community. While it is often thought of as an offline programming language, there are several ways to interface with it to control robotic hardware ‘in the loop’. As part of our own development we surveyed a number of different projects that accomplish this by using a message passing system and we compared the approaches they took. This post focuses on bindings for the following message passing frameworks: LCM, ROS, DDS, and ZeroMQ.

The main motivation for using MATLAB to prototype directly on real hardware is to dramatically accelerate the development cycle by reducing the time it takes to find out out whether an algorithm can withstand ubiquitous real-world problems like noisy and poorly-calibrated sensors, imperfect actuator controls, and unmodeled robot dynamics. Additionally, a workflow that requires researchers to port prototype code to another language before being able to test on real hardware can often lead to weeks or months being lost in chasing down new technical bugs introduceed by the port. Finally, programming in a language like C++ can pose a significant barrier to controls engineers who often have a strong electro-mechanical background but are not as strong in computer science or software engineering.

We have also noticed that over the past few years several other groups in the robotics community also experience these problems and have started to develop ways to control hardware directly from MATLAB.

The Need for External Languages

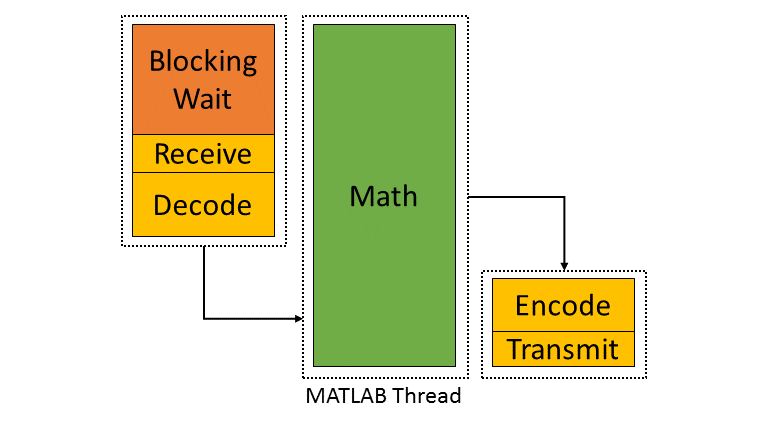

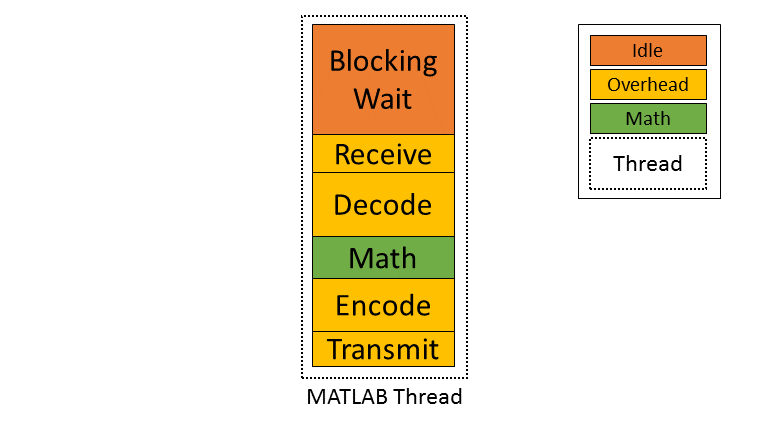

The main limitation when trying to use MATLAB to interface with hardware stems from the fact that its scripting language is fundamentally single threaded. It has been designed to allow non-programmers to do complex math operations without needing to worry about programming concepts like multi-threading or synchronization. However, this poses a problem for real-time control of hardware because all communication is forced to happen synchronously in the main thread. For example, if a control loop runs at 100Hz and it takes a message ~8ms for a round-trip, the main thread ends up wasting 80% of the available time budget waiting for a response without doing any actual work.

A second hurdle is that while MATLAB is very efficient in the execution of math operations, it is not particularly well suited for byte manipulation. This makes it difficult to develop code that can efficiently create and parse binary message formats that the target hardware can understand. Thus, after having the main thread spend its time waiting for and parsing the incoming data, there may not be any time left for performing interesting math operations.

Pure MATLAB implementations can work for simple applications, such as interfacing with an Arduino to gather temperature data or blink an LED, but it is not feasible to control complex robotic systems (e.g. a humanoid) at high rates (e.g. 100Hz-1KHz). Fortunately, MATLAB does have the ability to interface with other programming languages that allow users to create background threads that can offload the communications aspect from the main thread.

Out of the box MATLAB provides two interfaces to other languages: MEX for calling C/C++ code, and the Java Interface for calling Java code. There are some differences between the two, but at the end of the day the choice effectively comes down to personal preference. Both provide enough capabilities for developing sophisticated interfaces and have orders of magnitude better performance than required. There are additional interfaces to other languages, but those require additional setup steps.

Message Passing Frameworks

Message passing frameworks such as Robot Operating System (ROS) and Lightweight Communication and Marshalling (LCM) have been widely adopted in the robotics research community. At the core they typically consist of two parts: a way to exchange data between processes (e.g. UDP/TCP), as well as a defined binary format for encoding and decoding the messages. They allow systems to be built with distributed components (e.g. processes) that run on different computers, different operating systems, and different programming languages.

The resulting systems are very extensible and provide convenient ways for prototyping. For example, a component communicating with a physical robot can be exchanged with a simulator without affecting the rest of the system. Similarly, a new walking controller could be implemented in MATLAB and communicate with external processes (e.g. robot comms) through the exchange of messages. With ROS and LCM in particular, their flexibility, wide-spread adoption, and support for different languages make them a nice starting point for a MATLAB-hardware interface.

Lightweight Communication and Marshalling (LCM)

LCM was developed in 2006 at MIT for their entry to DARPA’s Urban Challenge. In recent years it has become a popular alternative to ROS-messaging, and it was as far as we know the first message passing framework for robotics that supported MATLAB as a core language.

The snippet below shows how the MATLAB code for sending a command message could look like. The code creates a struct-like message, sets desired values, and publishes it on an appropriate channel.

%% MATLAB code for sending an LCM message

% Setup

lc = lcm.lcm.LCM.getSingleton();

% Fill message

cmd = types.command();

cmd.position = [1 2 3];

cmd.velocity = [1 2 3];

% Publish

lc.publish('COMMAND_CHANNEL', cmd);Interestingly, the backing implementation of these bindings was done in pure Java and did not contain any actual MATLAB code. The exposed interface consisted of two Java classes as well as auto-generated message types.

- The LCM class provides a way to publish messages and subscribe to channels

- The generated Java messages handle the binary encoding and exposed fields that MATLAB can access

- The MessageAggregator class provides a way to receive messages on a background thread and queue them for MATLAB.

Thus, even though the snippet looks similar to MATLAB code, all variables are actually Java objects. For example, the struct-like command type is a Java object that exposes public fields as shown in the snippet below. Users can access them the same way as fields of a standard MATLAB struct (or class properties) resulting in nice syntax. The types are automatically converted according to the type mapping.

/**

* Java class that behaves like a MATLAB struct

*/

public final class command implements lcm.lcm.LCMEncodable

{

public double[] position;

public double[] velocity;

// etc. ...

}Receiving messages is done by subscribing an aggregator to one or more channels. The aggregator receives messages from a background thread and stores them in a queue that MATLAB can access in a synchronous manner using aggregator.getNextMessage(). Each message contains the raw bytes as well as some meta data for selecting an appropriate type for decoding.

%% MATLAB code for receiving an LCM message

% Setup

lc = lcm.lcm.LCM.getSingleton();

aggregator = lcm.lcm.MessageAggregator();

lc.subscribe('FEEDBACK_CHANNEL', aggregator);

% Continuously check for new messages

timeoutMs = 1000;

while true

% Receive raw message

msg = aggregator.getNextMessage(timeoutMs);

% Ignore timeouts

if ~isempty(msg)

% Select message type based on channel name

if strcmp('FEEDBACK_CHANNEL', char(msg.channel))

% Decode raw bytes to a usable type

fbk = types.feedback(msg.data);

% Use data

position = fbk.position;

velocity = fbk.velocity;

end

end

endThe snippet below shows a simplified version of the backing Java code for the aggregator class. Since Java is limited to a single return argument, the getNextMessage call returns a Java type that contains the received bytes as well as meta data to identify the type, i.e., the source channel name.

/**

* Java class for receiving messages in the background

*/

public class MessageAggregator implements LCMSubscriber {

/**

* Value type that combines multiple return arguments

*/

public static class Message {

final public byte[] data; // raw bytes

final public String channel; // source channel name

public Message(String channel_, byte[] data_) {

data = data_;

channel = channel_;

}

}

/**

* Method that gets called from MATLAB to receive new messages

*/

public synchronized Message getNextMessage(long timeout_ms) {

if (!messages.isEmpty()) {

return messages.removeFirst();

}

if (timeout_ms == 0) { // non-blocking

return null;

}

// Wait for new message until timeout ...

}

}Note that the getNextMessage method requires a timeout argument. In general it is important for blocking Java methods to have a timeout in order to prevent the main thread from getting stuck permanently. Being in a Java call prohibits users from aborting the execution (ctrl-c), so timeouts should be reasonably short, i.e., in the low seconds. Otherwise this could cause the UI to become unresponsive and users may be forced to close MATLAB without being able to save their workspace. Passing in a timeout of zero serves as a non-blocking interface that immediately returns empty if no messages are available. This is often useful for working with multiple aggregators or for integrating asynchronous messages with unknown timing, such as user input.

Overall, we thought that this was a well thought out API and a great example for a minimum viable interface that works well in practice. By receiving messages on a background thread and by moving the encoding and decoding steps to the Java language, the main thread is able to spend most of its time on actually working with the data. Its minimalistic implementation is comparatively simple and we would recommend it as a starting point for developing similar interfaces.

Some minor points for improvement that we found were:

- The decoding step fbk = types.feedback(msg.data) forces two unnecessary translations due to msg.data being a byte[], which automatically gets converted to and from int8. This could result in a noticeable performance hit when receiving larger messages (e.g. images) and could be avoided by adding an overload that accepts a non-primitive type that does not get translated, e.g., fbk = types.feedback(msg).

- The Java classes did not implement Serializable, which could become bothersome when trying to save the workspace.

- We would prefer to select the decoding type during the subscription step, e.g., lc.subscribe(‘FEEDBACK_CHANNEL’, aggregator, ‘types.feedback’), rather than requiring users to instantiate the type manually. This would clean up the parsing code a bit and allow for a less confusing error message if types are missing.

Robot Operating System (ROS)

ROS is by far the most widespread messaging framework in the robotics research community and has been officially supported by Mathworks’ Robotics System Toolbox since 2014. While the Simulink code generation uses ROS C++, the MATLAB implementation is built on the less common RosJava.

The API was designed such that each topic requires dedicated publishers and subscribers, which is different from LCM where each subscriber may listen to multiple channels/topics. While this may result in potentially more subscribers, the specification of the expected type at initialization removes much of the boiler plate code necessary for dealing with message types.

%% MATLAB code for publishing a ROS message

% Setup Publisher

chatpub = rospublisher('/chatter', 'std_msgs/String');

% Fill message

msg = rosmessage(chatpub);

msg.Data = 'Some test string';

% Publish

chatpub.send(msg);Subscribers support three different styles to access messages: blocking calls, non-blocking calls, and callbacks.

%% MATLAB code for receiving a ROS message

% Setup Subscriber

laser = rossubscriber('/scan');

% (1) Blocking receive

scan = laser.receive(1); % timeout [s]

% (2) Non-blocking latest message (may not be new)

scan = laser.LatestMessage;

% (3) Callback

callback = @(msg) disp(msg);

subscriber = rossubscriber('/scan', @callback);Contrary to LCM, all objects that are visible to users are actually MATLAB classes. Even though the implementation is using Java underneath, all exposed functionality is wrapped in MATLAB classes that hide all Java calls. For example, each message type is associated with a generated wrapper class. The code below shows a simplified example of a wrapper for a message that has a Name property.

%% MATLAB code for wrapping a Java message type

classdef WrappedMessage

properties (Access = protected)

% The underlying Java message object (hidden from user)

JavaMessage

end

methods

function name = get.Name(obj)

% value = msg.Name;

name = char(obj.JavaMessage.getName);

end

function set.Name(obj, name)

% msg.Name = value;

validateattributes(name, {'char'}, {}, 'WrappedMessage', 'Name');

obj.JavaMessage.setName(name); % Forward to Java method

end

function out = doSomething(obj)

% msg.doSomething() and doSomething(msg)

try

out = obj.JavaMessage.doSomething(); % Forward to Java method

catch javaException

throw(WrappedException(javaException)); % Hide Java exception

end

end

end

endDue to the implementation being closed-source, we were only able to look at the public toolbox files as well as the compiled Java bytecode. As far as we could tell they built a small Java library that wrapped RosJava functionality in order to provide an interface that is easier to call from MATLAB. Most of the actual logic seemed to be implemented in MATLAB code, but we also found several calls to various Java libraries for problems that would have been difficult to implement in pure MATLAB, e.g., listing networking interfaces or doing in-memory decompression of images.

Overall, we found that the ROS support toolbox looked very nice and was a great example of how seamless external languages could be integrated with MATLAB. We also really liked that they offered a way to load log files (rosbags).

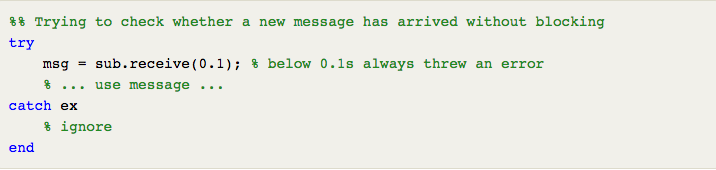

One concern we had was that there did not seem to be a simple non-blocking way to check for new messages, e.g., a hasNewMessage() method or functionality equivalent to LCM’s getNextMessage(0). We often found this useful for applications that combined data from multiple topics that arrived at different rates (e.g. sensor feedback and joystick input events). We checked whether this behavior could be emulated by specifying a very small timeout in the receive method (shown in the snippet below), but any value below 0.1s seemed to never successfully return.

Data Distribution Service (DDS)

In 2014 Mathworks also added a support package for DDS, which is the messaging middleware that ROS 2.0 is based on. It supports MATLAB and Simulink, as

well as code generation. Unfortunately, we did not have all the requirements to get it setup, and we could not find much information about the underlying implementation. After looking at some of the intro videos, we believe that the resulting code should look as follows.

%% MATLAB code for sending and receiving DDS messages

% Setup

DDS.import('ShapeType.idl','matlab');

dp = DDS.DomainParticipant

% Create message

myTopic = ShapeType;

myTopic.x = int32(23);

myTopic.y = int32(35);

% Send Message

dp.addWriter('ShapeType', 'Square');

dp.write(myTopic);

% Receive message

dp.addReader('ShapeType', 'Square');

readTopic = dp.read();ZeroMQ

ZeroMQ is another asynchonous messaging library that is popular for building distributed systems. It only handles the messaging aspect, so users need to supply their own wire format. ZeroMQ-matlab is a MATLAB interface to ZeroMQ that was developed at UPenn between 2013-2015. We were not able to find much documentation, but as far as we could tell the resulting code should look similar to following snippet.

%% MATLAB code for sending and receiving ZeroMQ data

% Setup

subscriber = zmq( 'subscribe', 'tcp', '127.0.0.1', 43210 );

publisher = zmq( 'publish', 'tcp', 43210 );

% Publish data

bytes = uint8(rand(100,1));

nbytes = zmq( 'send', publisher, bytes );

% Receive data

receiver = zmq('poll', 1000); // polls for next message

[recv_data, has_more] = zmq( 'receive', receiver );

disp(char(recv_data));It was implemented as a single MEX function that selects appropriate sub-functions based on a string argument. State was maintained by using socket IDs that were passed in by the user at every call. The code below shows a simplified snippet of the send action.

// Parsing the selected ZeroMQ action behind the MEX barrier

// Grab command String

if ( !(command = mxArrayToString(prhs[0])) )

mexErrMsgTxt("Could not read command string. (1st argument)");

// Match command String with desired action (e.g. 'send')

if (strcasecmp(command, "send") == 0){

// ... (argument validation)

// retrieve arguments

socket_id = *( (uint8_t*)mxGetData(prhs[1]) );

size_t n_el = mxGetNumberOfElements(prhs[2]);

size_t el_sz = mxGetElementSize(prhs[2]);

size_t msglen = n_el*el_sz;

// send data

void* msg = (void*)mxGetData(prhs[2]);

int nbytes = zmq_send( sockets[ socket_id ], msg, msglen, 0 );

// ... check outcome and return

}

// ... other actionsOther Frameworks

Below is a list of APIs to other frameworks that we looked at but could not cover in more detail.

| Project | Notes |

|---|---|

|

Simple Java wrapper for RabbitMQ with callbacks into MATLAB |

|

|

Seems to be deprecated |

Final Notes

Contrary to the situation a few years ago, nowadays there exist interfaces for most of the common message passing frameworks that allow researchers to do at least basic hardware-in-the-loop prototyping directly from MATLAB. However, if none of the available options work for you and you are planning on developing your own, we recommend the following:

- If there is no clear pre-existing preference between C++ and Java, we recommend to start with a Java implementation. MEX interfaces require a lot of conversion code that Java interfaces would handle automatically.

- We would recommend starting with a minimalstic LCM-like implementation and then add complexity when necessary.

- While interfaces that only expose MATLAB code can provide a better and more consistent user experience (e.g. help documentation), there is a significant cost associated with maintaing all of the involved layers. We would recommend holding off on creating MATLAB wrappers until the API is relatively stable.

Finally, even though message passing systems are very widespread in the robotics community, they do have drawbacks and are not appropriate for every application. Future posts in this series will focus on some of the alternatives.

tags: Algorithm Controls, c-Education-DIY, coding, MATLAB, programming, ROS, software

Florian Enner

is a Co-Founder of HEBI Robotics and a Principal Systems/Software Engineer at Carnegie Mellon University.

Florian Enner

is a Co-Founder of HEBI Robotics and a Principal Systems/Software Engineer at Carnegie Mellon University.

Related posts :

I developed an app that uses drone footage to track plastic litter on beaches

The Conversation

26 Feb 2026

Plastic pollution is one of those problems everyone can see, yet few know how to tackle it effectively.

Translating music into light and motion with robots

University of Waterloo

25 Feb 2026

Robots the size of a soccer ball create new visual art by trailing light that represents the “emotional essence” of music

Robot Talk Episode 145 – Robotics and automation in manufacturing, with Agata Suwala

Robot Talk

20 Feb 2026

In the latest episode of the Robot Talk podcast, Claire chatted to Agata Suwala from the Manufacturing Technology Centre about leveraging robotics to make manufacturing systems more sustainable.

Reversible, detachable robotic hand redefines dexterity

EPFL

19 Feb 2026

A robotic hand developed at EPFL has dual-thumbed, reversible-palm design that can detach from its robotic ‘arm’ to reach and grasp multiple objects.

“Robot, make me a chair”

MIT News

17 Feb 2026

An AI-driven system lets users design and build simple, multicomponent objects by describing them with words.

Robot Talk Episode 144 – Robot trust in humans, with Samuele Vinanzi

Robot Talk

13 Feb 2026

In the latest episode of the Robot Talk podcast, Claire chatted to Samuele Vinanzi from Sheffield Hallam University about how robots can tell whether to trust or distrust people.

How can robots acquire skills through interactions with the physical world? An interview with Jiaheng Hu

AIhub and Lucy Smith

12 Feb 2026

Find out more about work published at the Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL).

Sven Koenig wins the 2026 ACM/SIGAI Autonomous Agents Research Award

AIhub

10 Feb 2026

Sven honoured for his work on AI planning and search.