Robohub.org

When robots become art: Interview with Yi-Wei Keng

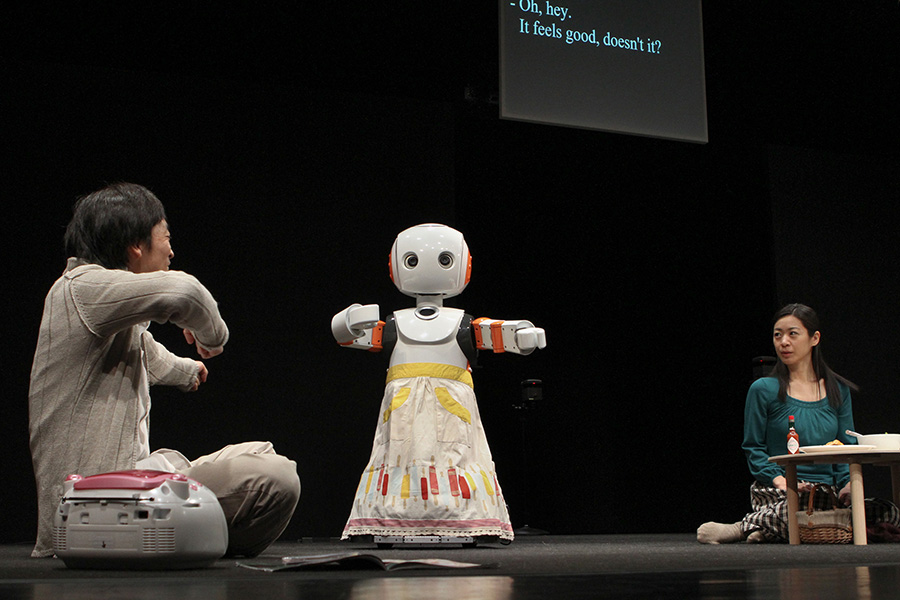

How can robotics help to enhance the development of the modern arts? Japan’s famous playwright, stage director Oriza Hirata and leading roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro launched the “Robot Theater Project” at Osaka University to explore the boundary between human-robot interactions through robot theater. Their work includes renditions of Anton Chekhov’s “Three Sisters”, Franz Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”, and their own play “I, Worker”. Their work has spread internationally to Paris, New York, Toronto and Taipei.

For this interview, we would like to invite their collaboration partner Yi-Wei Keng, director of Taipei Arts Festival, to share his insights on the intersection of robotics and the arts.

Interviewee: Mr. Yi-Wei Keng, Artistic Director of Taipei Arts Festival (TAF)

Interviewer: Dr. Yueh-Hsuan Weng, Co-founder of ROBOLAW.ASIA Initiative and Fellow at CLAST AI & Law Research Committee (Beijing) and Tech and Law Center (Milan)

Interviewer: Ms. Diane Chiang, Guest Editor at ROBOLAW.ASIA Initiative

WENG: Thank you for agreeing to an interview. Can you tell us a little about yourself and your background?

KENG: I have diverse backgrounds. I studied civic engineering in my first year at university and changed my focus to philosophy in my second year. After graduation and military service, I went to Prague to study non-verbal theater. I dedicated myself to disabled theater when I came back from Europe at the beginning of 2000s’. This multi-discipline experience helped me to think of arts in broader sense.

WENG: Can you introduce Taipei Arts Festival to our readers? What are the collaborations between Taipei Arts Festival and Robot Theatre project in recent years?

KENG: Taipei Arts Festival is the city’s festival, and was established in 1998. TAF gets its entire budget from the Taipei city government. I became the artistic director in 2012 and invited “Three Sisters, Android version” by Oriza Hirata and Hiroshi Ishiguro in 2013. Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro also visited TAF and gave public talks about his robotics work. Then in 2015 we invited their “La Metamorphose version Androide” to TAF.

WENG: What caused you to collaborate with Mr. Oriza Hirata? Did you face any challenges in implementing the piece into Taipei Arts Festival?

KENG: Well, it was really an accident. My wife read an article about the Robot Theatre Project in Monthly Art Magazine Bijutsu Techo. She told me about this and I did some research. I thought it was an interesting project, then I found Seinendan through my connections in Japan. Oriza Hirata gave a very positive response about our invitation. Everything went well during the festival, that is why we decided to invite Seinendan again in 2015.

WENG: Taiwan’s choreographer Yi Huang had used his KUKA robot companion to design his “Huang Yi & KUKA” robot choreography. Can you introduce more examples of robot choreography to us?

KENG: For example, French company Cie 111 made the “Sans Objet” in 2009, it was also a dance show with 2 dancers and an industrial robot, like Yi Huang’s KUKA project in 2013. French choreographer Blanca Li made the “Robot” in 2013 where the NAO Robot by Aldebaran Robotics to dance with real dancer.

WENG: In Japan, an art theater in Tokyo performed a theatrical rendition of Osamu Tezuka’s “Black Jack”. The character “Pinoko” was played by a robot created by Waseda University’s Takanishi Laboratory. The arms, legs, and body of the Takanishi Laboratory developed robot are detachable and equipped with 25 motors, so the robot can vividly resemble the Black Jack character. With your experience and expertise in performance art, what are your thoughts on this?

KENG: What surprises people most about robots or puppets is that we know they are objects but they act like they have soul inside. But if there were many robots in our life, then robots on stage would not be such a surprise. What matters is when the robot looks like a human being, then robot theater loses its meaning too because people can’t tell the difference from appearance. There are more and more animation films, but there is a psychological need to see real humans in films. That is what happens in animation film, we don’t want to see the animation, which shoots like the real movie, we want to experience the pleasure of difference and surprise.

CIANG: Is there a correlation between robotic theater and anthropology? If so, what is it? Can you share your insights from a puppetry aesthetics perspective?

KENG: As I say, if a robot looks like the real people on stage, then it loses its attraction for the audience. It is the same for puppet theater: the movement and design should remain dumpy and eccentric. In the future, androids in everyday life may confuse people if we can’t tell the difference between robots and human beings. We might kill someone which we declare as a robot, but in fact is a human being. Why is robot theater important? Because we could use theater to show the fictional situation which may happen in the future and discuss its meaning and possibility through story.

CIANG: In the 2016 Taipei Film Festival, there is a movie featuring a robot called “Sayonara”. This movie is an extension of Hirata and Ishiguro’s Robot Theater Project. They use an android as an actress in the movie. To human actors, what is the difference between 3D robotic theater and a 2D movie when they play with the android?

KENG: When you see the robot in a theater you confront the reality, and the statement from story becomes stronger than in the movie. There is a life event in theater but film is an illusion made by projecting lights on a screen.

CIANG: Can you tell us something about ethics debates in robot theater? Why do ethics matter to robot theater?

KENG: The main issue is the role of actors in theater. In 1908, theorist Gordon Craig declared that the Über-Marionette should replace the real actor in the future. But acting is not only imitation but also a creative process. Ethics about robot theater can help us to understand more about the essence of theater, robots and humanity.

CIANG: Do you think that it is possible to improve the performance of robots in society by borrowing experiences from performance theory?

KENG: If a robot wants to become human, they must look like a human and act like a human. So “act” has something to do with acting. According to the theory of mirror neuron, the audience can react with the acting from the stage, because their body acts the same way when similar situations happen, so the audience reacts. Acting technique divides from inside-out like Stanislavky system and outside-in like the Delsarte method. The performance theory of François Delsatre might help better than the inside-out technique since robots don’t act by feeling.

WENG: Researchers at the University of Oxford found that 47% of U.S. jobs are at risk of AI and automation in the next two decades. Do you agree that in the field of arts and drama, many future job opportunities will be replaced by robots? Or do you rather believe that new technology will create more opportunities for humans?

KENG: There are many puppet theaters in different cultures, and there exist theaters with real actors in these cultures too. There is no contradiction between having a robot actor and real actor. The emergence of robot actors could create a revolution in acting theory. The problem is not technology, but how we treat them.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also be interested in:

- A European perspective on robot law: Interview with Mady Delavaux

- Art meets robotics in Patrick Tresset’s OPLINE Prize entry

- Robots Podcast #171: Robotics in theatre, film and television, with Grant Imahara and Richard McKenna

- Flying robots perform 100th show on Broadway, using new localization technology and algorithms

- RoboThespian gets its own YouTube channel

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: art, c-Arts-Entertainment, Culture and Philosophy, cx-Politics-Law-Society, entertainment, human-robot interaction, humanoid, interview