Robohub.org

Machines can learn by simply observing, without being told what to look for

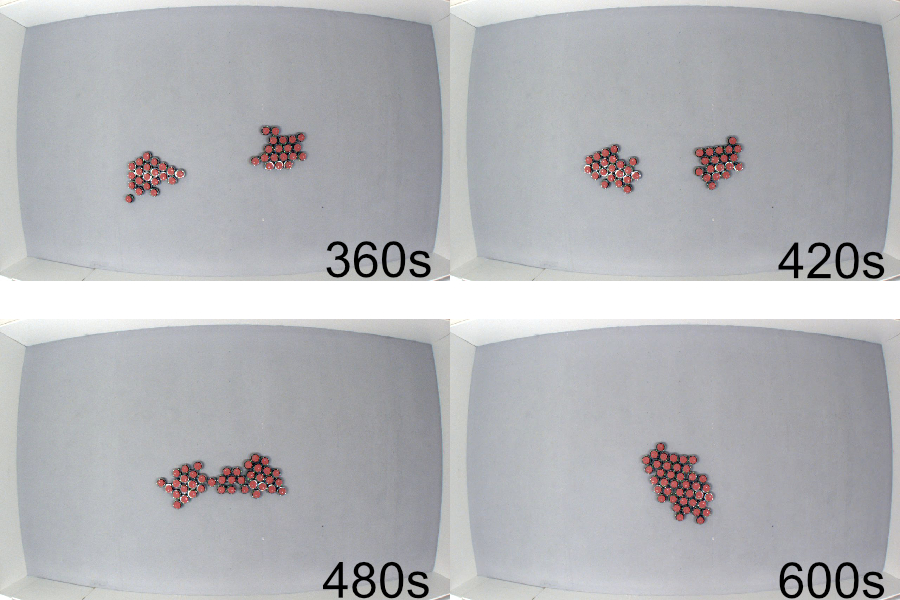

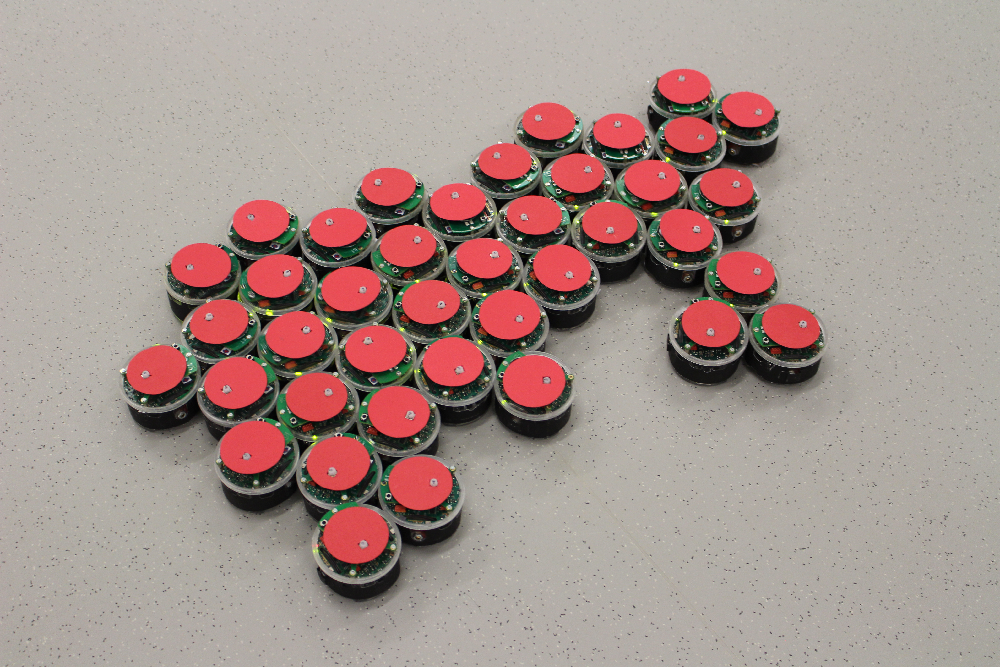

Image shows the aggregation behavior that the robots should learn (final snapshot of an already aggregated system). Credit: Roderich Gross

We have developed a new machine learning method at the University of Sheffield called Turing Learning that allows machines to model natural or artificial systems.

In Turing Learning, a machine optimizes models of a system under investigation. The machine observes the system, without being told what to look for. This overcomes the limitation of conventional machine learning methods that optimize models according to predefined similarity metrics, such as the sum of square error to measure the difference between the output of the models and that of the system. For complex systems, such as swarms, defining a useful metric can be challenging. Moreover, an unsuitable metric may not distinguish well between good and bad models, or even bias the learning process. This is the case, for example, for the swarm systems considered here – we prove that using the sum of square error metric one is unable to infer the behaviors correctly.

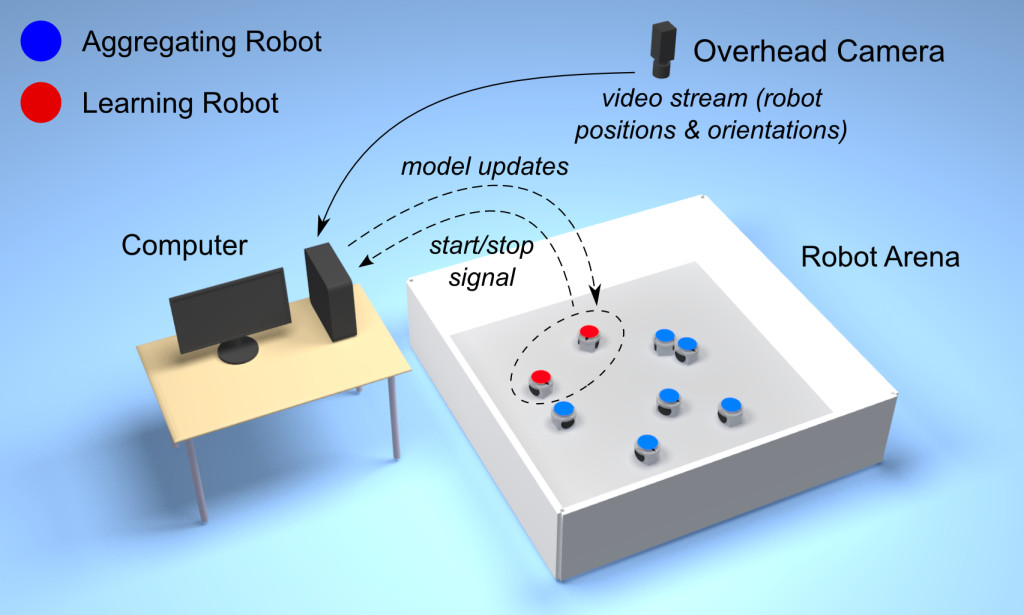

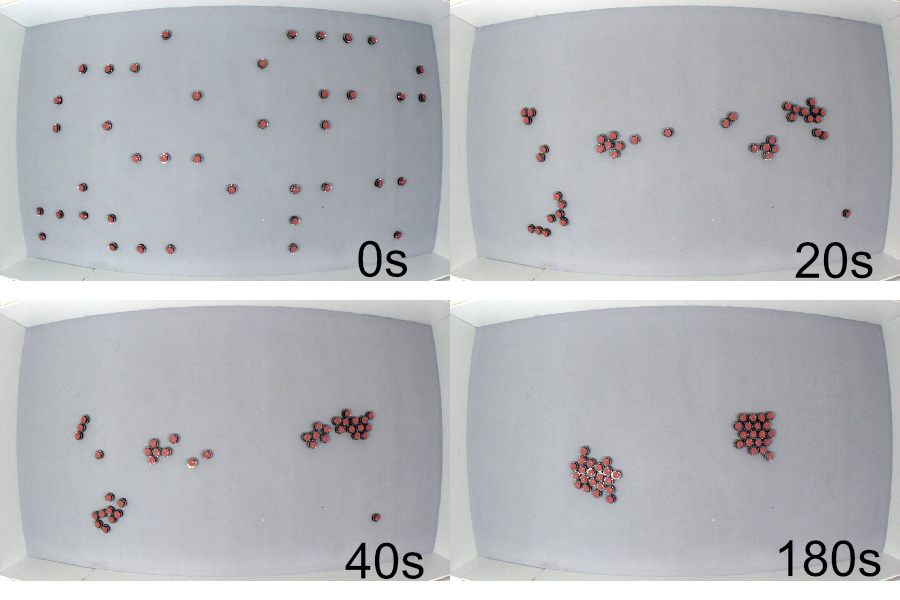

The Turing Learning setup for inferring swarm behaviors. The overhead camera observes both the system under investigation (aggregating robots) and the learning robots. Turing Learning simultaneously learns to model the behavior of the system and to discriminate between the aggregating and learning robots.

Turing Learning takes inspiration from the work of pioneering computer scientist Alan Turing, who proposed a test which required a machine to behave indistinguishably from a human in some respect. In this test, an interrogator exchanges messages with two players in a different room: one human, the other a machine. The interrogator has to find out which of the two players is human. If they consistently fail to do so – meaning that they are no more successful than if they had chosen one player at random – the machine has passed the test and is considered to have human-level intelligence.

Turing learning was successfully applied to infer swarm behaviors. We put a swarm of robots under surveillance and wanted to find out which rules caused their movements.To do so, we put a second swarm – made of learning robots – under surveillance as well. The movements of all the robots were recorded, and the motion data shown to interrogators. Unlike in the original Turing test, however, the interrogators in Turing Learning are not human but rather computer programs that learn by themselves. Their task is to distinguish between robots from either swarm. They are rewarded for correctly categorizing the motion data from the original swarm as genuine and those from the other swarm as counterfeit. The learning robots that succeed in fooling an interrogator – making it believe that their motion data were genuine – receive a reward. By doing so, Turing Learning can not only infer the behavioral rules of the swarm but also detect abnormalities in behavior.

Turing Learning could prove useful whenever a behavior is not easily characterizable using metrics, making it suitable for a wide range of applications. For example, computer games, could gain in realism as virtual players could observe and assume characteristic traits of their human counterparts. They would not simply copy the observed behavior, but rather reveal what makes human players distinctive from the rest. Turing Learning could also be used to reveal the workings of some animal collectives, such as, schools of fish or colonies of bees. This could lead to a better understanding of what factors influence the behavior of these animals, and eventually inform policy for their protection.

Reference:

The study is published in the September issue of the journal Swarm Intelligence.

If you liked this article, you may also want to read:

- Robots Podcast #197: Multi-agent systems and human-swarm interaction, with Magnus Egerstedt

- Bioinspired robotics #1: Swarm collectives, with Radhika Nagpal

- Evolving robot swarm behaviour suggests forgetting may be important to cultural evolution

- Surgical micro-robot swarms: Science fiction, or realistic prospect?

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

tags: c-Research-Innovation, machine learning, swarm robotics