Robohub.org

Team builds first living robots that can reproduce

AI-designed (C-shaped) organisms push loose stem cells (white) into piles as they move through their environment. Credit: Douglas Blackiston and Sam Kriegman

By Joshua Brown, University of Vermont Communications

To persist, life must reproduce. Over billions of years, organisms have evolved many ways of replicating, from budding plants to sexual animals to invading viruses.

Now scientists at the University of Vermont, Tufts University, and the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University have discovered an entirely new form of biological reproduction—and applied their discovery to create the first-ever, self-replicating living robots.

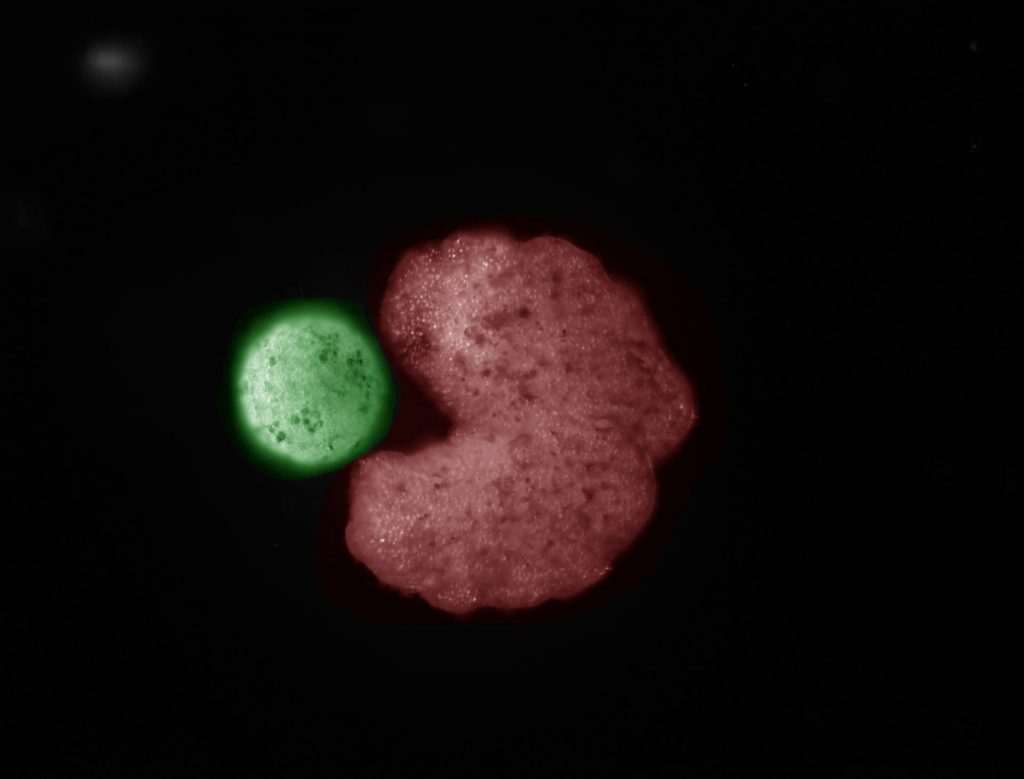

The same team that built the first living robots (“Xenobots,” assembled from frog cells—reported in 2020) has discovered that these computer-designed and hand-assembled organisms can swim out into their tiny dish, find single cells, gather hundreds of them together, and assemble “baby” Xenobots inside their Pac-Man-shaped “mouth”—that, a few days later, become new Xenobots that look and move just like themselves.

And then these new Xenobots can go out, find cells, and build copies of themselves. Again and again.

“With the right design—they will spontaneously self-replicate,” says Joshua Bongard, Ph.D., a computer scientist and robotics expert at the University of Vermont who co-led the new research.

The results of the new research were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Into the Unknown

In a Xenopus laevis frog, these embryonic cells would develop into skin. “They would be sitting on the outside of a tadpole, keeping out pathogens and redistributing mucus,” says Michael Levin, Ph.D., a professor of biology and director of the Allen Discovery Center at Tufts University and co-leader of the new research. “But we’re putting them into a novel context. We’re giving them a chance to reimagine their multicellularity.” Levin is also an Associate Faculty member at the Wyss Institute.

As Pac-man-shaped Xenobot “parents” move around their environment, they collect loose stem cells in their “mouths” that, over time, aggregate to create “offspring” Xenobots that develop to look just like their creators. Credit: Doug Blackiston and Sam Kriegman

And what they imagine is something far different than skin. “People have thought for quite a long time that we’ve worked out all the ways that life can reproduce or replicate. But this is something that’s never been observed before,” says co-author Douglas Blackiston, Ph.D., the senior scientist at Tufts University and the Wyss Institute who assembled the Xenobot “parents” and developed the biological portion of the new study.

“This is profound,” says Levin. “These cells have the genome of a frog, but, freed from becoming tadpoles, they use their collective intelligence, a plasticity, to do something astounding.” In earlier experiments, the scientists were amazed that Xenobots could be designed to achieve simple tasks. Now they are stunned that these biological objects—a computer-designed collection of cells—will spontaneously replicate. “We have the full, unaltered frog genome,” says Levin, “but it gave no hint that these cells can work together on this new task,” of gathering and then compressing separated cells into working self-copies.

“These are frog cells replicating in a way that is very different from how frogs do it. No animal or plant known to science replicates in this way,” says Sam Kriegman, Ph.D., the lead author on the new study, who completed his Ph.D. in Bongard’s lab at UVM and is now a post-doctoral researcher at Tuft’s Allen Center and Harvard University’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.

On its own, the Xenobot parent, made of some 3,000 cells, forms a sphere. “These can make children but then the system normally dies out after that. It’s very hard, actually, to get the system to keep reproducing,” says Kriegman. But with an artificial intelligence program working on the Deep Green supercomputer cluster at UVM’s Vermont Advanced Computing Core, an evolutionary algorithm was able to test billions of body shapes in simulation—triangles, squares, pyramids, starfish—to find ones that allowed the cells to be more effective at the motion-based “kinematic” replication reported in the new research.

“We asked the supercomputer at UVM to figure out how to adjust the shape of the initial parents, and the AI came up with some strange designs after months of chugging away, including one that resembled Pac-Man,” says Kriegman. “It’s very non-intuitive. It looks very simple, but it’s not something a human engineer would come up with. Why one tiny mouth? Why not five? We sent the results to Doug and he built these Pac-Man-shaped parent Xenobots. Then those parents built children, who built grandchildren, who built great-grandchildren, who built great-great-grandchildren.” In other words, the right design greatly extended the number of generations.

Kinematic replication is well-known at the level of molecules—but it has never been observed before at the scale of whole cells or organisms.

An AI-designed “parent” organism (C shape; red) beside stem cells that have been compressed into a ball (“offspring”; green). Credit: Douglas Blackiston and Sam Kriegman

“We’ve discovered that there is this previously unknown space within organisms, or living systems, and it’s a vast space,” says Bongard. “How do we then go about exploring that space? We found Xenobots that walk. We found Xenobots that swim. And now, in this study, we’ve found Xenobots that kinematically replicate. What else is out there?”

Or, as the scientists write in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences study: “life harbors surprising behaviors just below the surface, waiting to be uncovered.”

Responding to Risk

Some people may find this exhilarating. Others may react with concern, or even terror, to the notion of a self-replicating biotechnology. For the team of scientists, the goal is deeper understanding.

“We are working to understand this property: replication. The world and technologies are rapidly changing. It’s important, for society as a whole, that we study and understand how this works,” says Bongard. These millimeter-sized living machines, entirely contained in a laboratory, easily extinguished, and vetted by federal, state and institutional ethics experts, “are not what keep me awake at night. What presents risk is the next pandemic; accelerating ecosystem damage from pollution; intensifying threats from climate change,” says UVM’s Bongard. “This is an ideal system in which to study self-replicating systems. We have a moral imperative to understand the conditions under which we can control it, direct it, douse it, exaggerate it.”

Bongard points to the COVID epidemic and the hunt for a vaccine. “The speed at which we can produce solutions matters deeply. If we can develop technologies, learning from Xenobots, where we can quickly tell the AI: ‘We need a biological tool that does X and Y and suppresses Z,’ —that could be very beneficial. Today, that takes an exceedingly long time.” The team aims to accelerate how quickly people can go from identifying a problem to generating solutions—”like deploying living machines to pull microplastics out of waterways or build new medicines,” Bongard says.

“We need to create technological solutions that grow at the same rate as the challenges we face,” Bongard says.

And the team sees promise in the research for advancements toward regenerative medicine. “If we knew how to tell collections of cells to do what we wanted them to do, ultimately, that’s regenerative medicine—that’s the solution to traumatic injury, birth defects, cancer, and aging,” says Levin. “All of these different problems are here because we don’t know how to predict and control what groups of cells are going to build. Xenobots are a new platform for teaching us.”

The scientists behind the Xenobots participated in a live panel discussion on December 1, 2021 to discuss the latest developments in their research. Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

tags: bio-inspired, c-Research-Innovation, Micro