Robohub.org

The uncanny valet (or, Notes on the design of robot psychology)

This article outlines the problems of today’s phone and online help systems and offers solutions to conversational systems of tomorrow. The article is about the design of hearts and minds for robots, considers the virtual voice as a legitimate robot, and takes a fast pass at the psychology of robot-human interaction.

Part One: Another robot dream girl

I’m talking with this woman on the phone, interviewing her for a job. She’s got a slight southern twang, maybe from Georgia, telling me about her past work, and as we talk I’m struck by how perfectly presentable, alert, and smooth she sounds. Her voice is soft, tonally fluid, and she articulates her words precisely, belying a geeky disposition. Seems she’ll be perfect for the rather tricky tech support position we’ve got.

“Did you enjoy the work?” I ask.

“Sure, I like talking with people. I mean, as long as they don’t get upset it’s sorta fun.”

“You were working at a bank, right?”

“Yeah,” she laughs, “There were four of us working the phones and please press seven if you’d like one of us to call you back.”

“Sorry?” I ask.

“There were four of us on the phones and please press seven if you’d like one of us to call you back.”

I realize this robot has a bug, thank her, and hang up. I won’t hire that one.

Of course I never spoke with the uncanny woman again because the above story is fiction; a conversational system like this one is something of a dream among today’s robotics designers. She might have had a bug in her bonnet, but at least she could hold a conversation and answer questions, for the most part.

A system like the above, a Natural Language Processing system, is the heart and mind of a robot.

By contrast, consider what we have today: those irritating, tyrannical little phone robots that have replaced perfectly good humans: “Please push one if you would like to make a deposit. Please push two if you would like to hear these options again.” These non-player phone-workers are so brainless, grindingly slow, and weirdly rude that I find myself repeatedly pushing keys like 0 and # just to get to a real human.

Of course, from the cold eye of the bank (or whatever corporate conglomerate that employs these “Customer Relations Management” systems) these virtual robots reduce costs by replacing a fickle, distracted, complaining, prone-to-error, temperamental, sleep-deprived and very expensive call-center human with a voice recording. It saves the company money, time, and tons of overhead on things like worker’s insurance, sick-leave, replacements and the high cost of managing people. People are hard to manage, right? Voice recordings are not. People sleep at night, right? Voice recordings do not. So virtual robots, and this particular feral species of virtual robot – the phone robot – is a means of disintermediating the person from the knowledge: it is a means of scooping the knowledge out of the head of person that was doing the job and serving it to you, the customer, couched in smooth tones with a dose of saccharin-sweet politeness.

The intention is that robotic knowledge workers can replace human knowledge workers. But robotic workers are not capable of the job: rather than collaborate, they dominate; rather than answer questions, they force responses.

Bad robot, bad!

But virtual phone robots in their present form are bad at solving problems, they don’t learn, they’re inattentive, and they can’t even understand me. I have few options on what I can do, and I get pushed into decision trees that I don’t want. I feel herded like a cow, and with that little phone-robot nipping at my telephonic heels to move me into the right slot for processing, I more often than not either hang up or return to the website.

The intention is that robotic knowledge workers can replace human knowledge workers. But robotic workers are not capable of the job: rather than collaborate, they dominate; rather than answer questions, they force responses.

Bad robot, bad!

Part Two: The problem is the rotten brains

According to research from Nuance corporation, there are three main ways to improve phone robots. The first is to allow access to a real human. Two-thirds of the customers interviewed wanted that. About half of them said the system’s logical call flow was most important. And about forty percent of them said that the speech recognition component was the most important. So access to a live human, logical flow, and recognizing what’s been said are the three main problems with phone robots today.

If two-thirds of the users of a system that is supposed to replace a human say that the system can be most improved by providing access to a human, then that system is mostly broken.

Phone robots may save money, but they suck. We expect them to act like humans because they have a human voice, but instead they act like robots. This just adds to our frustration by reminding us that we do not have what we really wanted in the first place: a real human to talk to. The sound of the language is right, the annunciation is right, but it is a facade that just highlights the problem.

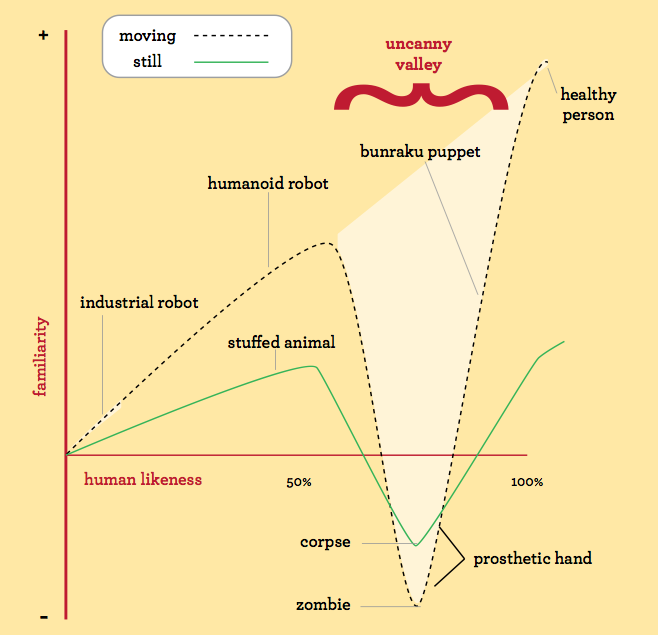

These phone robots live along the upper edge of an uncanny valley (if you do not know what the uncanny valley is please stop reading this, right now, and go look it up in Wikipedia).

Masahiro Mori pointed out many uncanny valleys, but the most famous ones are related to appearance and movement. We have yet to discover the many other uncanny valleys out there, especially as robots – and androids in particular – become progressively more human. As the systems become more capable and more interactive (phone robots today are almost always just voice recordings with a button-activated decision tree), more questions will arise. This will be exacerbated as physical robots become more human-like.

Should a robot’s voice sound like a human’s? Whose? Should a robot smell just like a person? If so, which one? What about how frequently the robot blinks? What about the tone of voice or intonation in sentences? What about social abilities?

Name a human trait and it will become an uncanny valley. These uncanny valleys will, in the coming decades, be explored and mapped. Mori just hit the tip of an icy moon that will chill, mortify, and entertain us for decades to come. We’re going to find uncanny valleys all over the pocked, lunar landscape of robotics design, and the one that will be most important to address is psychology.

First we have cognitive psychology. Consider all the traits that we humans pack into language, such as logical flow, attention, learning, language, and emotion. These are classically cognitive traits, each of which the phone robots of today should pay attention to. (Of course I mean “The designers of these systems should pay attention to.”)

Second we have social psychology. Consider all the traits that we humans pack into interaction such as politeness, collaboration, competition, and understanding. These are classically social traits, which the phone robots of today, or more accurately, their designers, need to consider.

Let’s lump them all together and imprecisely call them psychology. This is the uncanny valley that most concerns me. How a robot holds a conversation, thinks, and speaks seems the most important, and urgent, of the valleys ahead.

Robot psychology is urgent because it’s happening today. You have spoken with a phone robot and chances are (76%, according to Nuance) that you were not satisfied with it. So there’s a problem here.

Robot psychology is also important because we mimic the way we are spoken to. If you don’t believe me ask yourself why you speak the language you do. Reading this article means you probably grew up in a place where people mostly spoke English. What about your accent? Again, the people around you influenced you to speak that accent. They also influenced you to use the phrases, slang, jargon, words, ideas, and therefor fundamental psychological scaffolding you use to support your notion of reality. We do as we are done unto. When you listen to someone, their mind enters yours.

If a robot treats me in a rude manner chances are good that I’ll mimic that. If I’m going to be working, playing, living, or talking on the phone with a robot, I hope it will be a healthy example of both cognitive and social psychology that I can interact with and not be polluted by. As these systems become more prevalent their influence on our own behavior will increase.

This dynamic and interaction is both important and urgent.

It is why we are becoming our robots, and why our robots are becoming us. As they speak like us we will speak like them, and vice-versa.

Please press the down key if you would like to continue reading.

Part Three: The solution is to design robot psychology

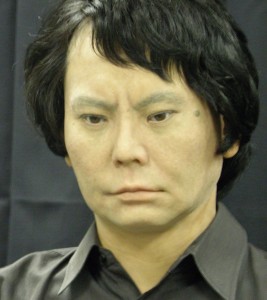

Once upon a time I had the odd luck to talk with the Geminoid F, the most realistic android on the planet (that was two years ago). It is the life work of Dr. Hiroshi Ishiguro. This uncanny experience would not have been so unsettling if Dr. Ishiguro’s doppleganger hadn’t been wading around like a zombie in the muck of the uncanny valley, but there it was and I – like the rest of the bottom feeders – was there with it. To this day, wish I had not gone.

Dr. Ishiguro is a moribund and curious fellow, and his robot more so. The problem, as I detailed in my book, “We, Robot” was that the robot was so real that it set an expectation of being human.

Please consider this face, and the heart and mind behind it. You do not, really, want its mind to enter yours, do you?

Communication – and staying out of uncanny valleys – is all about reflection. It has to do with mutual empathy and mutual agreements of closeness. It is about familiarity.

In my last article I talked about the design of androids, wrote about the designers that made them, and noted that the function of an android is psychological closeness. Androids (uh, or rather their designers) want you to feel comfy. The core notion of an android’s design is to set you up to interact with a computer in a traditional human setting. It’s about an expectation of human familiarity and something that reflects back to you a human image of yourself.

We humans are built such that we like talking with other humans. We like what’s familiar, what is, etymologically, of our family. We like talking with a familiar face, and if the robot doesn’t look like us then we tend to freak out a bit. After all, our friends usually look like us, dress like we do, and come from the similar socio-economic background. I might not like to admit it, but that’s usually the case. And, just as we like talking with a familiar face, we like talking with a familiar psychology; the psychology of our family. Our friends think like us, act like us, and like the same things. Birds of a feather, it has been said, flock together.

This is because much of the best communication is a reflection and collaboration. We like reinforcement, familiarity, and a reflection of our presence in the world. We do not like talking with someone who herds us, we do not like being told to push buttons, and we do not like phone robots because they fly in the face of almost all human-based computer-human interaction (CHI) theories (such as the android). Phone robots are a good example of a bad psychology.

If you were still a child, would you rather grow up talking daily with Ronald McDonald, Shrek, or Kung-Fu Panda? C’mon, choose one. Now what if a million children were to be forced, by your decision, to do the same?

As designers of robots we are faced with the same type of problem. As kids grow up interfacing with robotic personalities, and virtual robots, they will be influenced by, adopt the behaviors of, and intellectually be guided by these personalities. It is our responsibility to offer something better than junk food for the psyche.

Siri is about the best form of phone robot we have on the public market today. From my interactions with her she’s a little vapid, slightly sardonic, sometimes helpful, but mostly apologetic. When she makes a joke, which is sadly rare, or when she directs us toward (or steers us away from) some product, she is affecting our psychology.

There are some two hundred and fifty million versions of Siri out there. Let’s conservatively call that two million active versions of Siri functioning today. And I have no clue how many of Siri’s phone robot ancestors are out there, but we can safely say that the psychology of these systems is affecting the psychology of millions of people.

Ahead of us, the design steps for implementing android psychology are not evident, but we can follow in the footsteps of other people and extrapolate from character-based properties already in the wilds and public media of today.

If we look at how famous branded characters like Ronald McDonald or Kung-Fu Panda have been developed, marketed and sold, we can make out the guideposts for cultural preference and gender. If we look at archetypes like Darth Vader or Voldemort we can see how to design the bad guys. Superman and Gandalf give us clues on the good guys. Homer Simpson, Indiana Jones, Buzz Lightyear, George Bush, and Jacques Chirac are all personalities that have left an indelible public impression that we can model and use in designing psychology.

Presentation is important, too. Of course the system has to speak your language, and therefor regional preferences will guide the design of these robots. Dialects and accents count today. We can already see how Siri has been implemented with various accents such as American vs British. Gender will also continue to be important (70% of the automated voice systems in Europe are female, and in North America, 30%). After presentation we have the personality, the archetypes, and what the character knows.

Authors are the people that know about this kind of design. People who write character portraits, who ‘get’ dialogue, and who are socially alert duplicators of human interaction; people who make movies, people who conduct interviews, and, unfortunately, people who make advertisements: these are the people who can design systems that avoid psychology’s uncanny valley.

If we look at avatars in social media, and if we consider the movie industry we can see some other guideposts for the future of the psychology of android design. The most important is interactivity and reflection of shared interests. This takes us back to Nuance’s research.

Access to a real human will become increasingly rare. Regardless of what consumers want, the whole idea of a phone robot is 24 / 7 availability at a decreased price, and this is some thing a human cannot do. Next on Nuance’s list was the logical flow of the call and the speech recognition ability. These two important interactive components will surely get better in parallel as understanding one helps to improve the other.

Most of it will happen via mobile. Consumers in the United States – which roughly maps to much of the rest of the industrialized world – prefer to resolve their customers service issues using the telephone (90%), face to face (75%), company website or email (67%), online chat (47%), text message (22%), social networking site (22%). So it seems that while these conversational systems will live mostly in the phone, there will be a place for them in other media as well. They will live in the wires and waves that surround us, always available, often improving.

This is how the system becomes, finally, conversational. The irritating little herd-dog phone robot will evolve into something closer to a Geminoid. One day you will think you’re talking with a human on the phone, and then you will find yourself in a new uncanny valley. It won’t happen for at least another five years, but we’ll stumble into it eventually. The psychology of that robot will be a thing that touches you and guides you in ways that corporations like Google (who have powerful NLP tools today) Facebook (who released an NLP search system yesterday), can only begin to hint at.

They will be able to speak to you, sell to you, buy from you, offer medical guidance, marital guidance, and talk with you about your depression, your homework, your spouse, and your boss. Semantic Analytics, Social Analytics, and NLP will accurately measure your responses and the system will reply with a warm candor. Young men will ask about sex, old women will ask about hysterectomies, and all the other most awkward, personal, relevant, and important questions of life will be whispered, spoken, laughed, and sobbed into these many kinds of virtual androids that will gradually collect, like little honey bees collecting pollen and taking it back to the nest, your very own fears, loves, desires, hates and general, if I may say, psychology. The phone robots of tomorrow will become tiny transporters of emotion and personality. You will leave a voice recording and it will be taken, before you have hung up the phone, to some hive-mind.

The question we may ask these little bees is, “Where have you taken my personality?”

tags: AI, analysis, Design, Geppetto Labs, Mark Stephen Meadows, Natural Language Processing, Personality Design, robot, Uncanny Valley, virtual robot