Robohub.org

190

Fotokite Phi with Sergei Lupashin

Transcript included.

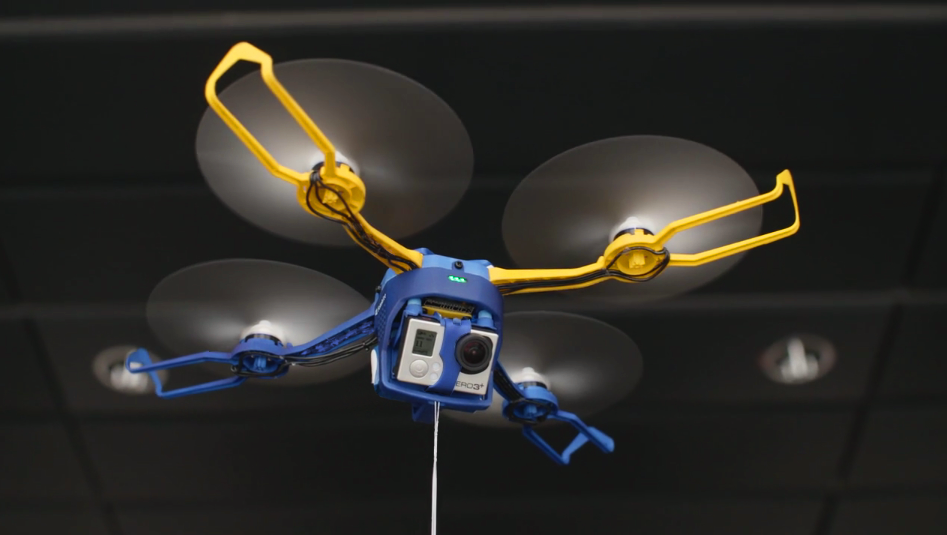

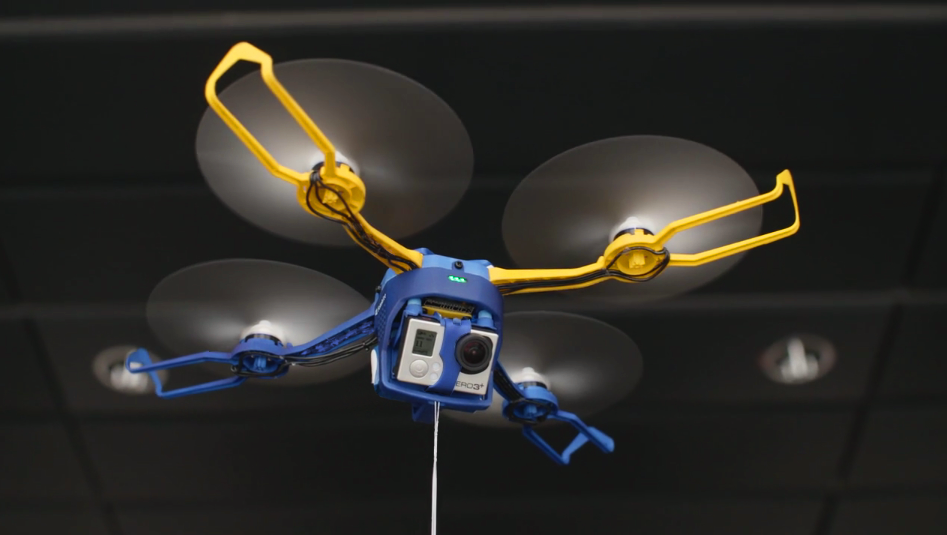

In this episode, Audrow Nash speaks with Sergei Lupashin about Perspective Robotics’ tethered flying camera, the Fotokite Phi, which is currently crowdfunding on Indiegogo. The Phi is a portable light weight GoPro-carrying quadrocopter that flies without a vision system or GPS, and instead uses the tension on the retractable tether to determine where it is in space. According to Lupashin, the tethered leash provides a natural, easy-to-learn and accountable interface for controlling the Phi.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aglTWdI-4Bo

Sergei Lupashin

Sergei Lupashin is the founder of Perspective Robotics, the Swiss company behind the Fotokite. Previous to that he worked in aerospace and participated in robotics competitions such as the DARPA Grand+Urban Challenges (autonomous cars). He was chief architect for the ETH Flying Machine Arena, where he enjoyed torturing little quadrocopters until they learned to do flips. He holds a BS in Elec & Comp Engineering from Cornell, an MSc + PhD in Mechanical Engineering from ETH Zurich (topic: aerial robotics) and is a TED Fellow. Sergei is passionate about building devices that are usable and useful in the real world.

Links:

- Download mp3 (14.3 MB)

- Subscribe to Robots using iTunes

- Subscribe to Robots using RSS

- Link to Fotokite Phi Indiegogo campaign

Transcript

Audrow Nash: Hi welcome to the Robots Podcast. Can you introduce yourself to our listeners?

Sergei Lupashin: I’m the founder of Perspective Robotics, a company based in Zurich, Switzerland that is behind the Fotokite, the Fotokite Pro and the Fotokite Phi.

Audrow Nash: Fotokite Phi is currently crowdfunding on Indiegogo. Can you tell me a bit about the campaign and its goal?

Sergei Lupashin: This is our first attempt at building a product for consumers. We started off by building the Fotokite Pro, which is a specialized, more expensive product designed to be used for broadcast. With the Fotokite Phi we have tried to make something much more accessible both in terms of price and usability. It’s extremely portable and it can be used in lots of different situations.

We are trying to raise a minimum of US $300,000 … It’s a hardware product, so you have to build critical mass to make it accessible for a wider audience. It’s a very exciting step for us.

Audrow Nash: Can you describe the Phi?

Sergei Lupashin: I’m holding one in my hands right now … It’s a small quadrocopter that holds a GoPro, and it weighs only 12 ounces – about the weight of a small can of soda.

What’s unique about it is that you control it via tether. You hold onto what is essentially a glorified dog leash with some electronics, and you launch the Phi just by turning it on, giving the quadrocopter a twist, and letting it fly.

Audrow Nash: This doesn’t have the same sensors as most drones. Of course it has an IMU, but you’ve removed GPS, correct?

It’s a different experience from traditional drones because the interface is so physical: you feel pretty much the smallest motions of the Fotokite in the air through the string.

Sergei Lupashin: Exactly. One of the things we use the tether for is to figure out where the Phi is relative to the user. A normal drone does that by having a GPS receiver or having some sort of machine vision to figure out where it is. In our case, we use a tether that is kept under tension at all times. By calculating where that tension force points, the Fotokite actually knows where it is relative to you.

This changes the dynamics of the system because it’s completely self-contained and the whole experience exists around the user. If you are walking down the street, hiking in the mountains or walking down a trail with this thing attached to you, it will naturally follow with you without any special algorithms.

Audrow Nash: Can you tell me a bit about the leash, how it works, how it keeps constant tension?

Sergei Lupashin: When it’s hovering it doesn’t fly straight up; it flies at a small angle and it stays not above you but to the side. The leash is spring-loaded, so the Fotokite produces a bit of extra force to keep the tether under tension.

You can just point the Fotokite in the direction you want to launch it, but once it’s flying, how do you tell it to turn? How do you tell it to move around? We wanted to get away from the concept of having to use a joystick or your smart phone to do that. Inside the leash are electronics that connect to the Fotokite while it’s flying; to control it you hold down the button on the side of the leash and you rotate your wrist. That motion of your wrist – that motion of the leash – is translated into a command for the Fotokite.

Audrow Nash: What kind of commands can you give? Can you have it rotate to look around?

Sergei Lupashin: Yes. Right now there are just two modes of interface. One mode is in-phase rotation. For example, if I want to take a panorama, I would launch the Fotokite straight up and then I would hold down the first button and rotate my wrist. The Fotokite would then rotate in place and capture the full 360 panorama. The other mode lets you control the position of the Fotokite relative to you.

Audrow Nash: The angle?

Sergei Lupashin: Exactly. We usually speak in terms of ‘elevation’ and ‘orbit’. For example, if you look at the stars in the sky, a star has a certain elevation above the horizon. To control the elevation in our case, holding down a button while you move your wrist up and down will move the Fotokite either from a horizontal position to a vertical one (relative to you), or vice versa. It basically controls the vertical angle where it flies.

Moving your wrist in the horizontal plane will cause the Fotokite to orbit, meaning that it will slowly reorient itself around you. If you keep doing this motion, the Fotokite will complete a circle around you at a given elevation.

You can get really neat matrix-style shots of yourself. Or you can use it to do sophisticated shots, using the Fotokite like a flying steady-cam.

Audrow Nash: How long does it take to train someone to use the Fotokite?

The beauty of the system is that there is nothing active in this tether, so you can attach any string to the Fotokite and it will still work just fine.

Sergei Lupashin: It’s a different experience from traditional drones because the interface is so physical: you feel pretty much the smallest motions of the Fotokite in the air through the string.

We did a number of demos for both expert drone users and people who haven’t touched one before. Getting it to fly is surprisingly straightforward: you show someone how to do it, they’ll repeat the motions, and it will work immediately.

To get really unique shots and smooth video requires a bit of skill. The nice thing is, with the tether, you can use your own physical movements to control it and to keep it from crashing into things. It’s a lower stress experience than what you see with traditional drones.

Audrow Nash: Speaking of crashing into things, what happens if it bumps into an object? Or if someone runs into the tether, the tether becomes taught in a different direction, and that tension is released suddenly?

Sergei Lupashin: In terms of bumping into things, we have protective coverings that extend past the motors, so most of the time an object would bump into the protective coverings first. That helps to prevent crashes, and it also helps to give the user confidence in being around the Phi.

In terms of the tether getting caught in things, the beauty of the system is that there is nothing active in this tether, so you can attach any string to the Fotokite and it will still work just fine.

For example, if you’re filming the rooftop of your house and you’re trying to get over to the other side of it, you can actually fly the Fotokite over the rooftop and then get it such that the tether touches the edge so you can sling-shot it over. It will simply use that new fixed point as the new reference point, and this happens naturally.

Explained in words it sounds weird, but just imagine flying a kite where the lift is generated by the kite itself: if you grab the kite string, and someone pulls it away, it will still fly at the same angle – but relative to that new point.

Audrow Nash: Does this mean that you don’t really need the smart leash? Is it just for controlling the Fotokite, so that it rotates and you can change the vertical angle?

Sergei Lupashin: The smart leash is there to make the system complete. Most folks just want to use the system to capture a picture or video. We didn’t want to make them have to go find a string.

The leash is a convenience: it’s nicely built, it has a spring, and it has electronics that allow control.

The Phi’s arms fold up with the propellers on the inside so that you can put it into its tube-shaped carrying case. It’s about the size of a thermos, and you fit it into your backpack.

I should also mention that the Fotokite Phi folds, because in real life, transportation is a major issue. The Phi is pretty unique in that it has a lock mechanism that makes a satisfying click when it locks. And when you unlock it, the arms fold up with the propellers on the inside so that you can put it into its tube-shaped carrying case. It’s about the size of a thermos, and you fit it into your backpack.

Audrow Nash: And everything fits in there?

Sergei Lupashin: Yes, the leash and everything.

Audrow Nash: The tether is very nice from the perspective of controlling the drone. What are some other advantages of using tethers?

Sergei Lupashin: The tether wasn’t actually the original idea.

I was finishing my PhD and looking at different schemes for aerial systems. This was in Raff D’Andrea’s lab – he has been on your podcast as well. We were exploring some different approaches using gestures – with Kinnect for example. But all of these systems were based on machine vision, which is incredibly sensitive to the conditions you are operating in. Sunrise, lens flare, darkness, water – all of these things confuse the system.

The tether completely changed the dynamics of the conversation between the operator, the vehicle and the public. It makes this device much more acceptable in public.

So the question was: how do we get localization and interaction in the most robust way possible? That’s where the idea of the tether came from: it was originally a technical solution to let a flying vehicle figure out precisely where it is relative to you, without relying on sensitive systems like GPS or machine vision etc.

Then, when we made the first demo, it turned out to be a really elegant way to interact with the system. The tether completely changed the dynamics of the conversation between the operator, the vehicle and the public. I think this was actually one of the most exciting moments of this process, because as a technologist you don’t foresee it; you see the tether as a technical solution and nothing else. But then it turns out to also have all of these facets that are not technical, but rather about the experience, and how people see the product.

In the end, the tether changes the Fotokite from being another drone into something that is more of a companion flying device. It’s a very personal device … it’s more like a kite, and people treat it that way.

One parallel is to imagine being at the park and having your dog on a leash versus not on a leash: for some people it’s fine, but other people just get freaked out by dogs that are not leashed. I think we see some of that with drones from a privacy perspective. What we found is that having a tether changes the conversation and makes this device much more acceptable in public.

Audrow Nash: There’s accountability because you can see where the operator is?

Anyone – no technical background required – intuitively understands the chain of responsibility with this device.

Sergei Lupashin: Exactly. Anyone – no technical background required – intuitively understands the chain of responsibility with this device.

Audrow Nash: Can you tell me a bit about how this and similar technology has been used in journalism, for example the Fotokite Pro?

Sergei Lupashin: The original inspiration for the Fotokite came from aerial footage of the Bolotnaya Square demonstrations in Russia in 2011. It was after the federal elections, and it was a big demonstration right in the center of Moscow. The footage was captured pretty much by pure chance from a drone – quite a big drone with an SLR camera. There was this one image, a panorama really … it’s amazing how well it transmitted the scale and atmosphere of the event.

The people who took that footage were very lucky that they happened to have the right equipment; they were professionals so they could do it safely, and they happened to have the right permissions. But we’ve seen many other examples where people haven’t been able to get these perspectives and cover events like this as well as they could have been covered. For example, in Ferguson, Missouri where there was a no fly zone was imposed, which many believe was done to keep the media out.

We also found out that having a physical connection usually changes the regulatory aspect. For example, in Switzerland and France, after some conversation with the regulators we were able to get special rules for tethered devices that are much more permissive than traditional drones. From a regulatory perspective, the usual thought process is focused on safety, whereas privacy is more universal and not usually what they are basing rules on. From a safety perspective, in Zurich for example, it was prohibited for a while to fly drones commercially. The Fotokite was allowed based on the tether and specifically based on the idea that the tether restricts the height of the device.

Many regulators think of how much energy would be dissipated if the device falls in an uncontrollable fall, and there is a magic number of 66 joules … if you fall and it dissipates 66 joules then you are magically unsafe.

Audrow Nash: How much is 66 joules?

Sergei Lupashin: This is potential energy, so it’s Mass X Gravity X Height. Imagine a 6 kg bowling ball falling from about a meter …

It’s a safety margin. With the Fotokite’s tether you can restrict the length of the tether and thus the height, so you can guarantee that under no conditions are you going to exceed that safety limit.

Audrow Nash: So you can only extend to the length of the tether unless you can’t get high enough to possibly generate 66 joules on complete impact?

Sergei Lupashin: Yes, that’s right.

There are other aspects they look at, too, like system robustness. For example, how many subsystems or how many components do you have in your critical loop? How many subsystems are there such that if one of them fails you have an uncontrolled system or a catastrophic failure? In a traditional drone, GPS is usually in that critical loop, as is your radio system, and if you lose your GPS or radio you will crash into something. With the Fotokite, there is no GPS and if the radio cuts out, it will just fly in the same position.

Audrow Nash: How does it look for other countries with these exemptions? For example, do you believe the US will permit tethered drones to fly? Do you think they will give exemptions similar to Switzerland and France?

Sergei Lupashin: It’s very hard to predict which way the US regulations are going to go right now. If you look at the history of it, just over the past few months regulations were proposed that were extremely lenient and permissive. Most recently there has been a massive push over certain events … you’ve probably heard of the person shooting drones down over their property. So it’s really hard to predict.

It’s a challenge since all of this technology is new and people don’t quite know how to differentiate it. For example, what is a tethered drone? If you attach a fishing line to a DJI, is it now tethered? I kid you not that there are commercial products out there for sale that offer exactly this, and they promise to get you around regulations.

We are trying to be proactive and come up with commonsense and observable definitions of what it means to be tethered.

We are trying to be proactive and come up with commonsense and observable definitions of what it means to be tethered. For example, I really believe that the tether has to be loadbearing, meaning that under typical flight it should actually be under tension, and it should be rated for some sort of tension that responds to the vehicle.

Audrow Nash: For a hobbyist or someone that just wants to use the Fotokite Phi to take pictures of themselves, do these regulations mean anything outside of countries that have exemptions for tethered drones? Or is it only for commercial use and journalism that the regulations apply?

Sergei Lupashin: Regulations generally apply to commercial use, but there are exceptions specifically generally cities, populated centers, and in the US national parks. If you go for a hike to the Yosemite or Yellowstone National Park in the US, for example, you can’t use a drone right now. These are the kind of the frontlines where we’re going to see how consumer drones get regulated in the future.

Audrow Nash: Going back to the Phi, how does the tether affect battery life?

Sergei Lupashin: In the Pro we use the tether to supply power, so we can fly forever. In the Phi we couldn’t do that because of cost and complexity, so we use a standard one-port battery. The trick there is that, since you’re producing extra tension to keep the tether taut, you are wasting a tiny bit of battery life, but on the other hand, if you imagine how a kite actually uses the wind, you could be using a less than normal power to stay afloat.

The current prototypes fly for around 7-10 minutes. For the production units, we are aiming for 15 minutes of typical flight time. The battery is swappable in the field, so you always have the option of replacing it.

Audrow Nash: How did you decide to move from a journalism drone – the Fotokite Pro – to a consumer drone with Fotokite Phi?

Sergei Lupashin: With the Fotokite Pro we realized after talking to existing drone users that the tether has a unique advantage especially in the niche of live reporting. In journalism you typically want to operate next to people and next to something that’s happening, and you don’t want to add tension to that situation. It’s a very unique niche where the tether makes a huge difference. The powered tether is important because journalists can keep the device afloat and not worry about battery life.

But we always wanted to build something a wider reach, and a few months ago we finally decided it’s now or never, because everything is developing very quickly. The Phi is is a big experiment for us to see how well we can use the tether to build a new user experience.

A lot of people see the Phi for the first time and they think it’s just a quadrocopter on a string, but the deeper story is to look at the engineering behind it, using the tether as a different interface approach.

A lot of people see the Phi for the first time and they think it’s just a quadrocopter on a string, but the deeper story is to look at the engineering behind it, using the tether as a different interface approach.

Audrow Nash: Is this a way of addressing the interaction bottleneck with robotics technology?

Sergei Lupashin: That’s right. Have you tried reprogramming your alarm clock lately? [laughs]

In robotics labs we tend to come up with ridiculously complex systems. I’m sure they can do a lot in principle, but they are very difficult to interact with. I think this somehow echoes with many robotics products that have already come out. An example of that is in Japan when the Fukushima incident happened. Arguably Japan has some of the most advanced robotics, especially for search and rescue, anywhere in the world. But they really struggled to make a difference in that situation. And I think a lot of problems are because of interaction, because of training, and because of the complexity of the systems.

The inspiration for the Phi is really to try to cut across that and come up with a smooth and low-friction user experience, where even someone who has never touched robotics could be shown how to use this device and they could naturally take it, use it themselves, and feel confident and empowered by it.

Audrow Nash: Thank you.

Sergei Lupashin: Thank you.

All audio interviews are transcribed and edited for clarity with great care, however, we cannot assume responsibility for their accuracy.

tags: aerial photography, Algorithm Controls, c-Aerial, Crowd Funding, cx-Consumer-Household, drones, ETH Zurich, Fotokite, startup, Switzerland, UAVs